Big Bang Data at London’s Somerset House

Artists’ inventive and strange ways to analyze their personal world and the universe around us

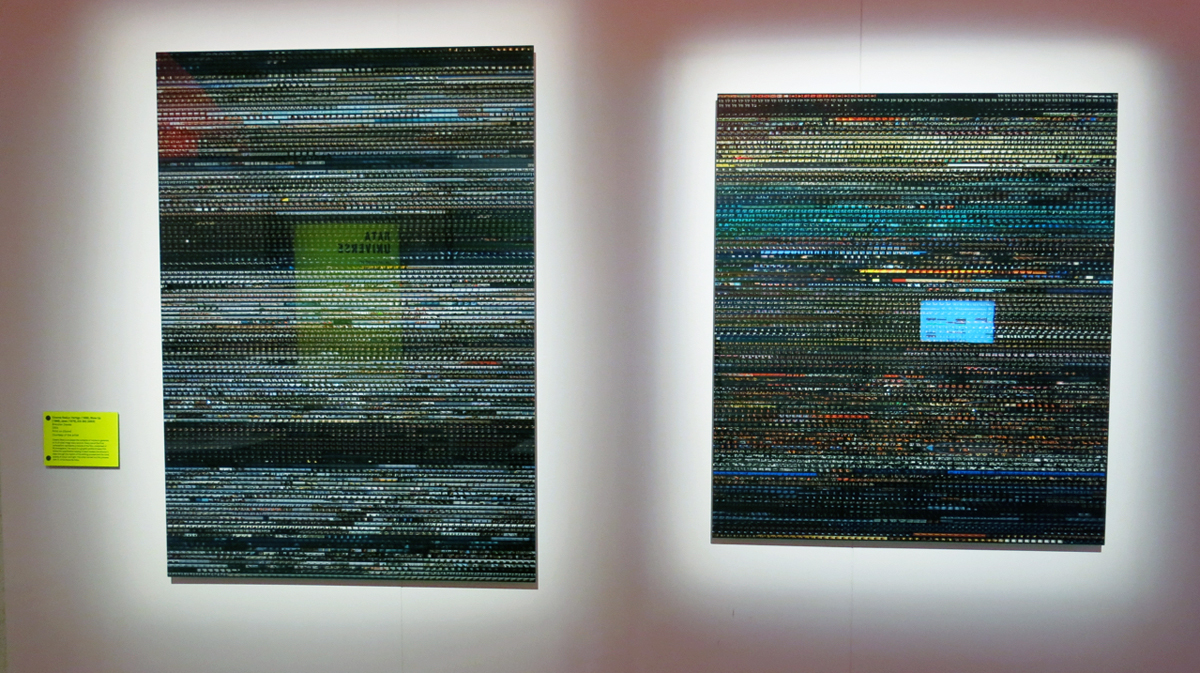

Do you know where your cat lives? You probably do and, if you ever tagged it #cat in a publicly available photo online, chances are so does Owen Mundy. Mundy is the artist behind the project “I Know Where Your Cat Lives” and one of the people taking part in “Big Bang Data”—on show now at London’s Somerset House. Through the eyes of a number of international new media artists, the exhibition looks at the datafication of our world and how it affects everyone in a series of recently commissioned and rarely seen works. When discussing of the exhibition, co-curator Olga Subirós cites Lev Manovich, saying: “19th century culture was defined by the novel, 20th century culture by cinema, the culture of the 21st century will be defined by the interface… So many artists care about privacy issues, and this is a new way to approach them. We want to spark conversations and debates.”

It’s exciting to see how the various artists involved in the show have made use of current technology, with personal works proving to be the most interesting and poignant. Among them are CH favorite Nicholas Feltron’s annual reports that each cover a year in his life in the form of pie charts, graphs and other information. Close by, Jaime Serra’s simple, differently colored lines on a black background turn out to be a visualization of the various kinds of sex the artist and his wife had in 2010, with nine different practices detailed. It’s simultaneously sweet, awkwardly intimate, sexless, clinical and scientific—physical closeness reduced to statistics.

The exhibition also has a special London Situation Room. The most closely-watched city in the world, Londoners are used to surveillance, and it’s a “really reactive” city, says Amanda Taylor of data visualization studio Tekja. For the show, Tekja created a piece that uses three real-time data streams (from Twitter, Instagram and Transport for London) to show what’s happening in the city right now. “When a football game in Germany was cancelled due to a terror alert, we saw (London football arena) Wembley stadium light up with supportive tweets straight away,” Taylor says, as an example of how immediate the data is and how quickly Londoners react to data. The piece is thoroughly engaging and completely immersive—once you start wondering about why people tweet more about work in the north of the city than in the south, or clicking on underground stations to see where the next train is heading, the temptation is to see London as a SimCity-like computer game, but it also makes you feel closer to its inhabitants.

If one side of Big Bang Data shows people taking the personal and making it impersonal, the flip-side is pieces like that of Giorgia Lupi and Stefanie Posavec, whose “Dear Data” project, which was finished this year, is also on display. Lupi and Posavec sent each other postcards every week for a year, with extremely detailed, hand-drawn data on various subjects from their lives. They vary from data on how many times they said the word “data” in a week, to data on how many urban animals they saw in a week, or how many negative thoughts they had. The postcards become mini artworks—as well as a tangible representation of how time-consuming data visualization is when it isn’t done by machines.

A lot of the works at Somerset House show the advantages of data visualization, like Ingo Günther’s wonderful, deeply disturbing “World Processor” which displays information on globes. It uses the world map to visualize issues like the fact that 51 of the 100 top economies in the world are corporations, not countries, with companies accruing an annual gross income larger than the GDP of some countries. This is when Big Bang Data is at its best: in the hinterland between information and art.

It’s also fun to see that, despite the advantages of modern technology, digital data can still be an unreliable narrator. Scroll through Mundy’s #cat pictures long enough, and you’ll see an image of a guy who’s tagged himself #cat next to a sign for the Caterpillar construction company—proof that some information is still a bit too nuanced to be understood by an algorithm.

“Big Bang Data” is on now through 28 February 2016 at London’s Somerset House (Strand, London WC2R 1LA) and entrance costs £13.

Images by Cajsa Carlson