Charged: Daguerre’s American Legacy

An exhibition showcasing 100 of the first photographic portraits ever made

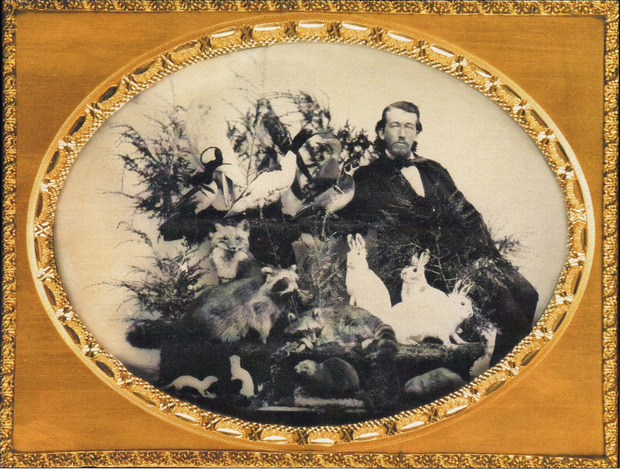

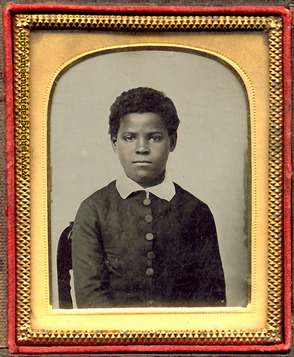

Following two highly acclaimed runs at museums in greater-Paris, photo-historian William B. Becker’s collection of daguerreotypes—the first widespread photographic process involving imagery cast upon a highly polished silver surface—is about to make its American debut at the MIT Museum‘s Kurtz Gallery for Photography. Becker, who has spent the past four decades collecting early photos, is also the founder of the American Museum of Photography, a virtual museum showcasing historic imagery and encouraging its research and preservation. The exhibit at the MIT Museum features 100 early photographs from Becker’s collection, many of which originated during the daguerreotype boom of the 1840s and ’50s. Each one offers a dual window into the past, serving not only as a testament to the historic technology but also capturing the eye and artistry of those behind the camera.

“The development of photography historically was a continuous effort to produce images more quickly, more easily, and more cheaply, and yet the daguerreotype was in some ways never surpassed pictorially.”

The exhibit’s US edition is primarily the work of Gary van Zante, the MIT Museum’s Curator of Architecture and Design, who worked alongside initial curators Becker and François Brunet, a Professor of American Art and Literature at the University of Paris–Diderot. Van Zante, who has curated more than 50 exhibitions, explains to CH that this one is unique in that it “offers an opportunity for an interesting historical juxtaposition. Image making today, with iPhones and other devices, is so fast and effortless, requiring virtually no thought. And here is a process in which the image is very slowly, painstakingly made, but has a detail and presence and transparency that cannot be achieved digitally.” He adds that “the development of photography historically was a continuous effort to produce images more quickly, more easily, and more cheaply, and yet the daguerreotype was in some ways never surpassed pictorially.”

Daguerre was something of an open-source pioneer in that he shared the secrets of his revolutionary photo process with the public in 1839, changing the art world—and the world in greater sense—forever. His practical, cost-efficient method would allow for an explosive proliferation of photography that would extend into America. There, the early adopters of the medium would modify and hone the technology while rushing to open portraiture studios so as to cash in on the craze. Daguerreotype facilities would open, and hordes would flock to have their portraits captured and placed upon shimmering mirror-like surfaces. It was the start of both an industry and an art form, and this wondrous, haunting portraiture would define the image and identity of the time.

In addition to the daguerreotypes, “Daguerre’s American Legacy” features other forms of 19th-century photographs, including ambrotypes, tintypes and paper prints, all of which are on loan from Becker. The exhibition aims to offer interpretations of early codes in portraiture, as well as the relationship between subject and photographer. One of the central throughlines of the exhibit is the notion that American photography evolved into a means of communicating personal attributes well beyond documentary. By the end of the 19th century, a “photographic fiction” developed that resulted in studio creations ranging from ghosts to blizzards.

On display is the only documented portrait from the world’s first-ever photography studio, which opened in NYC in 1840.

As for the figures on display in the exhibit, there are abolitionists and slaves, coquettes and literary women, cross-dressers and chicken-pluckers, as well as laborers such as firemen, brick-makers, cabinet makers and even a newsboy. The portraits are the work of both obscure artists and some of America’s first masters of the medium: Southworth & Hawes of Boston, Jeremiah Gurney of New York and Marcus A. Root of Philadelphia. Also on display is the only documented portrait from the world’s first-ever photography studio, which opened in NYC in 1840.

Meanwhile, the Kurtz Gallery for Photography at the MIT Museum is a relatively new venue, having opened in 2012. The version of “Daguerre’s American Legacy” here offers a number of departures from its initial iteration. As van Zante notes, “It is a very different show in its presentation. We’ve added new artifacts such as cameras and other examples of photographic technology, and we have an entirely different organization of the images. The text is also new.” The curator also notes: “Some of this exhibition is about how an individual collector shapes how we understand history through his own interests, attitudes and motivations.”

Of the 100 works, van Zante explains, “All are quite small, often no bigger than the palm of the hand, which is another way this exhibition provides a counterpoint. We have become accustomed to looking at very large photographs in museums and galleries and in advertising. Our digital tools allow us to zoom in on anything. In the 19th century, technology limited the size of images, and they required close and careful looking, something we are not so skilled at anymore.” This perspective of scope and scale is just one more reason that “Daguerre’s American Legacy: Photographic Portraits (1840-1900) from the William B. Becker Collection” is worth seeing. The show will run from 18 April 2014 through 4 January 2015.

Images courtesy of Wm. B. Becker Collection/American Museum of Photography