Fine Artist Ronan Day-Lewis’ Solo Presentation at SPRING/BREAK Art Show Los Angeles 2022

Awash in imagination, the exhibit “See Through” blends eccentric creatures, otherworldly landscapes and unusual font

In Culver City last week, the 2022 edition of LA’s Spring/Break Art Show greeted guests with powerful, often thought-provoking paintings and sculptures. Punctuating this refreshing assemblage of up-and-coming talent, NYC-based fine artist (and filmmaker) Ronan Day-Lewis presented See Through, a solo exhibition curated by the Brooklyn-based artist-run space Tomato Mouse. Day-Lewis’ paintings—which ranged from large-scale scenic imaginings to anxious font-based strips—subverted reality, indulged in soft collisions of color and invited viewers to question the narrative within.

“Spring/Break differs from other art fairs in that it’s artist- and curator-driven, known for innovative projects that don’t happen elsewhere,” Tomato Mouse curator Rebecca Bird says of their participation. This exhibition is the third collaboration between Day-Lewis and Tomato Mouse, which has been headquartered in Brooklyn’s Ocean Hill/Brownsville neighborhood since 2012.

“It fits with the homemade ethos of Tomato Mouse,” Bird continues. “I was attracted by the theme of this year’s iteration, Hearsay/Heresy, as a chance to curate art that relates to Medieval painting traditions. Beyond a personal love of Northern Renaissance paintings, biblical subjects in painting reflect a time when there was a shared set of narratives that artists drew on, in contrast to today, so it speaks to fraught notions of truth and universality.”

Day-Lewis actually proposed the exhibition. “He had completed this beautiful and interconnected body of work that together forms something complete, a set of interlocking premises and questions,” Bird says of the oil pastel on unprimed canvas paintings. “The work is all from the last year; very concise as a moment.”

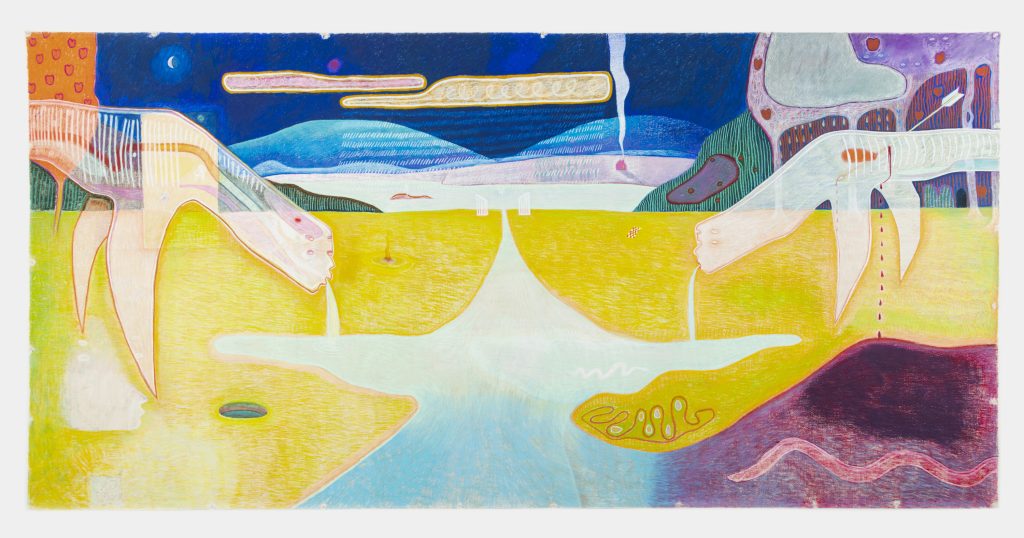

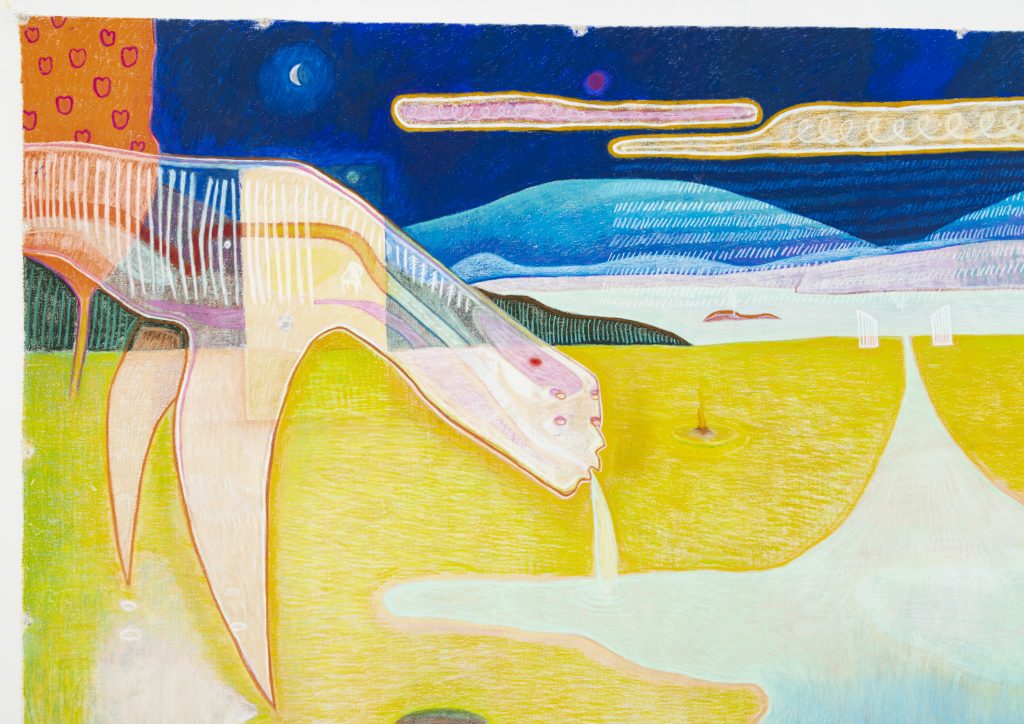

To walk into Spring/Break was to catch site of Day-Lewis’ largest work, “The Beginning (Listen! Your Brother’s Blood Cries Out To Me From The Soil.),” which stretched across one wall of the Tomato Mouse booth. For it, the artist was inspired by a vision, an accompanying sensation and a desire to solve a mystery, as well as “an instinct that it needed to be big enough to get lost in,” he explains. “With ‘The Beginning,’ I knew what I wanted the painting to feel like way before the narrative aspect took form. My parents live in the Hudson Valley overlooking the river, and that place has such a strange beauty to it—a sense of infinity, like you’re standing at the edge of the world. That became a jumping-off point.”

“It felt like I was living in the painting for five or six months,” he continues. “As I went, ideas would suggest other ideas, and elements would materialize almost of their own accord. There was a lot of frustration that came from the physical limitations of smearing such a big piece of fabric with little sticks of pigment, but at a certain point the painting started telling me what to do, and I was like, ‘Oh, so this is what you are.'” Day-Lewis uncovered the biblical Cain and Abel tale within and worked toward making it his own.

Anachronistic attributes populate the canvas: a ball, a chair and more. They walk viewers down unexpected paths. “Objects and places have always been very charged for me,” Day-Lewis continues. “I’m more nostalgic than I’d like to be, but there’s a way that objects carry the past, like portals. They let us speak to each other through time. The chair and the ball come from impressions of times and places from my childhood.” Erstwhile, he adds, “My creatures are sort of emotional x-rays, so threading these things through them felt right. Like an interpolation of memory, embedding the personal in the mythic. Scattering these little details is also a way of asking the viewer to come closer, to lose themselves in the world of the painting.”

All of the artist’s works are cast in equally curious colors, lending a further sense of removal from reality. “Color has always been essential to how I understand things,” he says. “It’s a feeling, a mystery, a way into a secret world. Certain colors can immediately make me happy or sad. When I was a teenager, Irma Ostroff, my art teacher, always put such an emphasis on it. I remember letting some pink creep into the edge of a self-portrait, and from her reaction, I knew that gesture had completely changed the painting. I started to see color not just as a compositional tool or a means to render real-world objects, but as a vessel for the things you can’t put into words.”

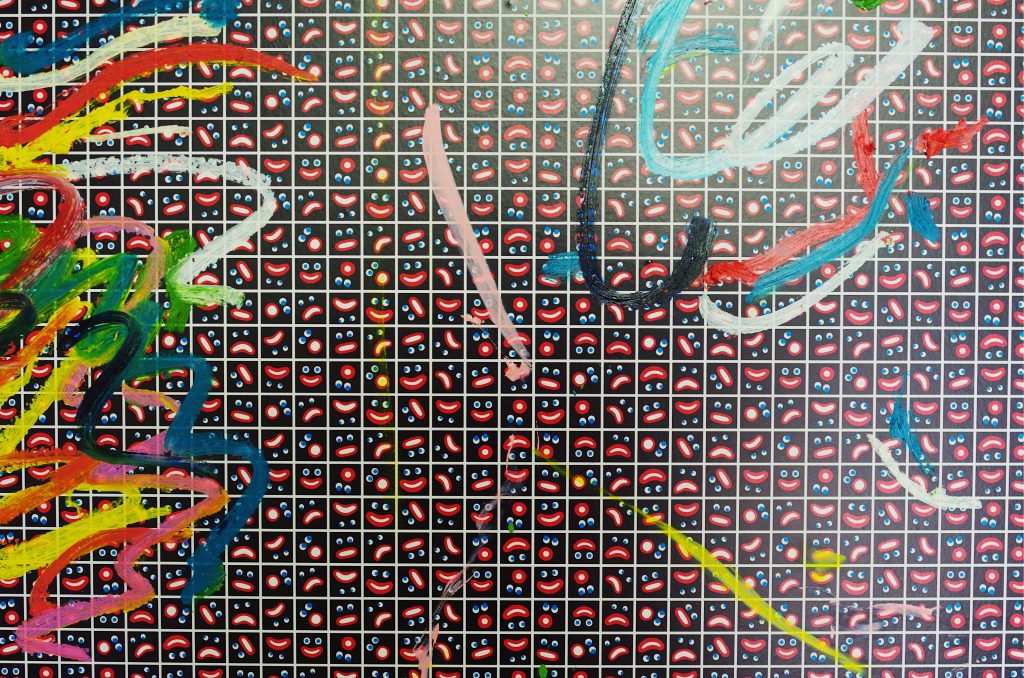

Day-Lewis juxtaposes these mythical works with (often anxiety-inducing) text-based art. “I see the more mythical paintings as embodiments of what’s going on beneath the texts,” he explains. “We’re constantly having these failures of communication which are easy to dismiss as silly or inconsequential, but I think these contemporary attempts and failures to connect with each other are actually just new manifestations of almost primordial archetypes and emotions. We’ve sort of been trying to express the same things to each other for millennia. A big part of my practice as a painter has become an attempt to connect the present moment to something eternal.”

Of note in the text works is Day-Lewis’ eccentric font. During an art class, he started “adding more spokes to my Es, the way I had written them as a young child. It was a way of undoing knowledge and returning to a more instinctive way of making. There’s a clumsiness to the font which I think is important. I like reproducing these sleek, fleeting, very digital ephemera in a laborious, permanent, kind of crude way. I’m a terrible texter, so maybe it’s a kind of exorcism, or at least a way of slowing things down. Everything moves so fast.”

Day-Lewis graduated from Yale in 2020 and his trajectory has just begun. It was drawing that brought him to art at a very early age. “My first experience with oils was extremely frustrating—the paint felt so slippery and stubborn—but when I started realizing the possibilities of color, I began to love painting as much as I already loved drawing. I already feel very privileged to have the time and space to make and show my paintings, but ultimately I want to continue growing as an artist and connecting to more people through my work.”

As for their Spring/Break installation, Bird says curation was an organic process, oriented toward arranging the paintings “to both intrigue viewers who are new to the work and give them a way in, visually, to the thought processes behind it.” She adds, “At first glance it seems as if we are looking at two bodies of work—the hallucinatory pastoral scenes of a world populated by mythological beasts counterposed with what appear to be transcribed text messages in pastel letters that glow like low-fi neon. The relationship between the two is key, and they both needed space to breathe on their own and to connect.”

“We assembled 12 text message pieces into a conversation made of compounding miscommunication and constant apology next to the entrance to the booth,” she continues. “While it has a humorous appeal, it speaks to the anxiety many of us have about failure to respond appropriately to others’ needs. The pang of the disconnect is more acute in the flatness of digital communication, the paucity of this language.” Elsewhere, “small pastoral images of banishment” co-exist across from “scenes set in primordial forests.”

“Traveling from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, bringing these enormous paintings with us, planning and preparing the booth and installing in the space of a few days was a bit like a reality game show,” Bird adds. “The whole fair came together quickly in a gutted warehouse building with beautiful enormous skylights. We didn’t know what the space we were given would be like until the day we arrived. It was delivered rough, with variously colored panels for walls, so the challenge and opportunity was to create a finished presentation somewhat from scratch in two days.” Together, curator and artist succeeded in transporting visitors into a universe unto itself.

Images courtesy of Ronan-Day Lewis, Tomato Mouse and SPRING/BREAK Art Show