Gehard Demetz: The Invocation

The Italian sculptor explores the transition to adulthood through his life-size wooden sculptures of children at Jack Shainman Gallery

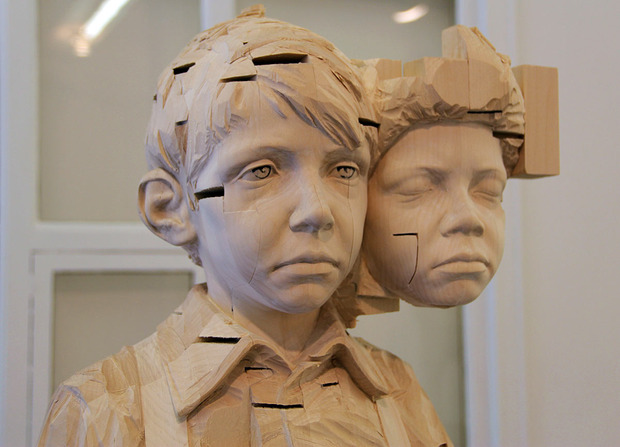

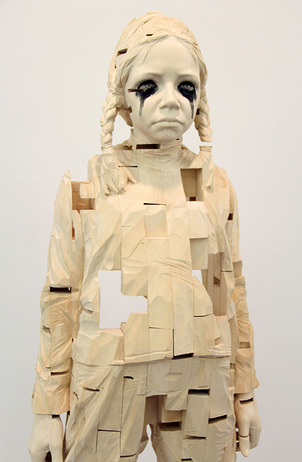

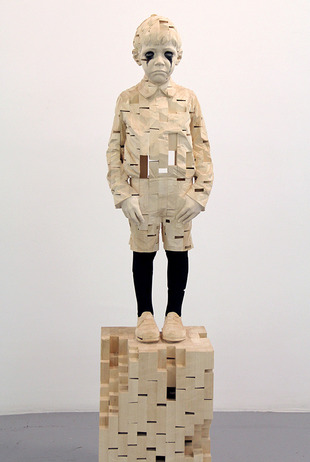

Gehard Demetz could perhaps be called a modern-day Geppetto—but instead of woodcarving puppets with curiously growing noses, he creates lifelike limewood sculptures of children that captivate as much as they unsettle. Each child holds a special object—not a pacifier or teddy bear, but objects associated with adulthood: belts, blinders, guns, smudged makeup and more. From afar, these realistic objects look like they are another material, but they’re made from the same wood, just painted. While the introspective gazes on most of the children’s faces look troubled and sad, they convey a sense of power over the viewer, especially as they stand with authority atop plinths, confronting us eye-to-eye. We met with the artist at the Jack Shainman Gallery on the opening day of his second solo exhibition show “The Invocation,” now on view until the end of this month.

Demetz was born in Bolzano, the northern region of Italy located by the Dolomites where the rare dialect of Ladin is spoken. Living so close to the border has exposed the sculptor to a wide range of philosophical and artistic influences; he cites Neo Rauch, Gerhard Richter, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Boris Groys as a few of his inspirations.

He blends classical woodworking techniques with an original approach—each statue is built piece by piece—”like a puzzle or Legos”—and then carved. This process is especially visible when viewing the children’s backs, which expose a hollow body created by wood blocks of various sizes, as well as through the intentional gaps. The smaller sculptures take around one month to complete, but the more complex, larger sculptures such as “For My Fathers” took more than two months.

“For My Fathers,” a sculpture that towers over the viewer, is a boy holding a belt (perhaps to be used as a whip) at arm’s length. “He proposes the belt to have the possibility of becoming an adult. This is part of the story,” says Demetz. The boy makes this movement to different fathers; whether it is his father, grandfather, fatherland or even a priest as father. Demetz suggests imagining the sculpture without the belt; revealing that the child would appear to be demonstrating the Nazi salute.

What’s remarkable is how Demetz is able to render the children’s faces so smooth; this precision is juxtaposed against the unpolished, rough texture he carves into the hair and clothes. The results are life-sized (or larger) children carrying objects that look eerily realistic. “Their use is ornamental, like a fashion accessory,” Demetz says, pointing at the makeup spilling from the boy’s eyes in “Mother’s Darling.” It’s indeed a powerful statement-making accessory.

“It’s important to me,” Demetz says about his choice to make children his muse. “Rudolf Steiner, who founded the Waldorf school, said that children, until six years old, have the possibility to feel the unconscious.” After six years, this is lost—and this vulnerable transition of self-realization, no longer a child but not quite yet an adult, is something that Demetz is trying to explore. “And they are at this age,” Demetz says, pointing to one of his works. The artist has two children of his own, but says that the personal motivation behind his artwork is searching through his own childhood. “I think I always played alone and I spoke to myself so much—like I was speaking with ghosts. When I read Steiner, he gave me a reason to make this kind of art,” he says.

In “Their Bodies Smell Different,” a girl kneels in prayer with her eyes closed, her hands resting on the kneeling rail—next to a shoe, which is fact carved out of wood. It was inspired by the 2008 incident where Iraqi journalist Muntadhar al-Zaidi threw his shoes at then President George W. Bush in Baghdad. “Is this shoe for the priest or for the church?” asks Demetz of his own sculpture. Demetz reveals that he is especially fond of his sculptures that have closed eyes, because it is like they are searching for their own religion.

“Stones in My Pocket” (which was shown at Art Miami last December) features a boy wearing rubber gloves, the kind used for dishwashing, but also with a gun in his mouth. Noting that many children enjoy trying on their father’s and mother’s clothes, slipping into shoes and jackets and such even though they’re much too big, Demetz points out that this boy wears the gloves of an adult, but loses his ability to use his hands. “The gun is a fetish idea, like a ball-gag in the mouth. He is trying out same things as adults—but he loses his voice.” They’re both a potential metaphor for the sacrifice that children make to become adults, but in return, these children gain something else—they require respect and reflection; a reaction by the viewer.

“The Invocation” is now on exhibit until 31 May 2014 at Jack Shainman Gallery, 513 West 20th St in Manhattan. Keep an eye out on the gallery’s newest space The School in Kinderhook, NY which officially opens 17 May with a performance and exhibition by Nick Cave.

Photos by Nara Shin