Interview: Adam Broomberg

One half of London-based duo Broomberg and Chanarin discusses his interpretation of contemporary war photography

Photography isn’t a practice that’s conducive to duos; in fact, from a more general perspective, most contemporary visual artists are solitary figures. Thus, the story of duo Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin is a slightly peculiar yet significant one. Together—through their photography—they provoke political and social questions that many are too content or afraid to ask. And, while recognizing its limitations at the same time, the duo has also tested and pushed the boundaries of photography as a medium by creating contexts for images that continually redefine their nature and purpose. So it makes sense that their 2011 altered book project, “War Primer 2” would be selected for the Musuem of Modern Arts’ New Photography 2013 exhibition, making its debut in New York City.

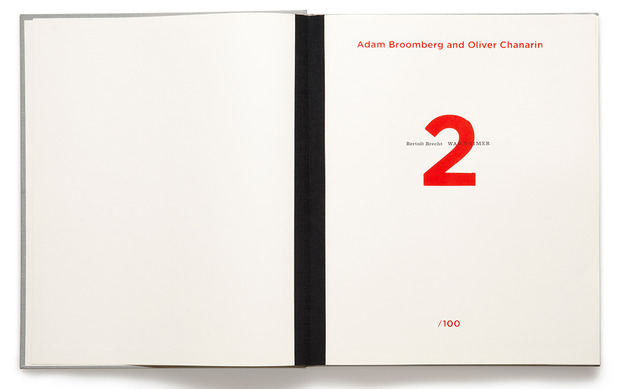

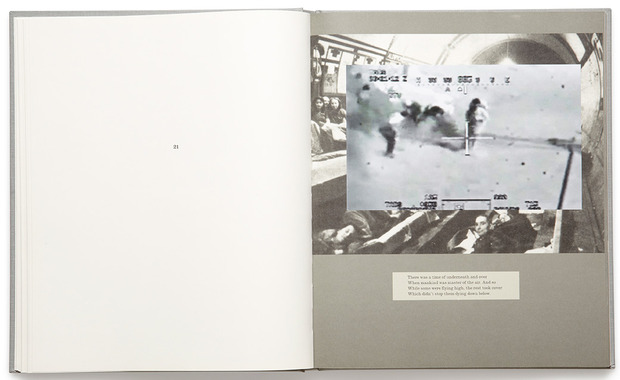

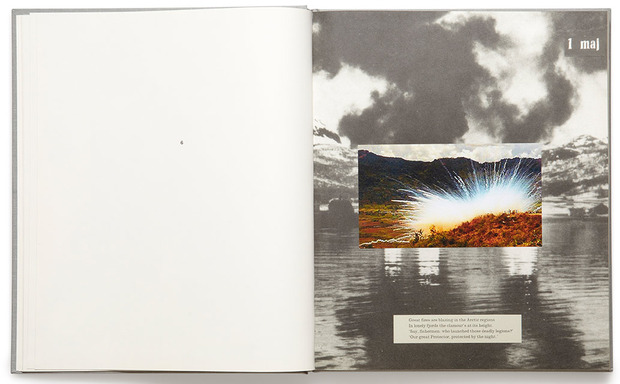

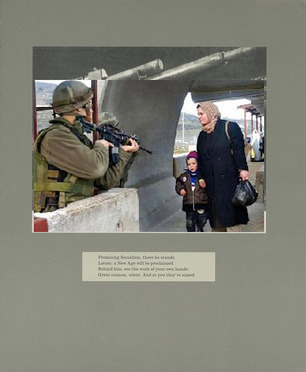

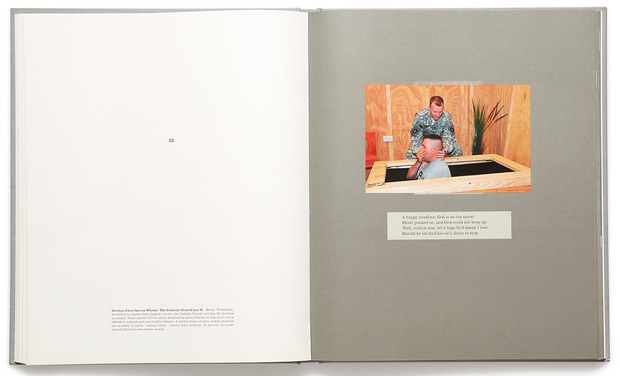

“War Primer 2” is a modern-day reinterpretation of German poet Bertolt Brecht’s 1955 book “War Primer.” Brecht wrote four-line poems as captions for World War II clippings, in order to decipher the bourgeoisie-controlled mass media images and portray them from an objective point of view. In this era, when the bourgeoisie no longer have control and anyone—even a civilian or drone—can snap a photo, Broomberg and Chanarin applied the “War Primer” technique to contemporary war images, silkscreening text and superimposing low-resolution screenshots over Brecht’s pages. Since 2011, Broomberg and Chanarin have already done two further explorations of Brecht’s “War Primer.”

We met with Broomberg in Soho—just down the street from the non-profit exhibition space Apexart where the pair have another exhibit—to dissect some of his thoughts on war photography, the invasiveness of cameras, and working in tandem.

Let’s start off with how you and Oliver met.

In South Africa, in a tiny town called Wuppertal on holiday when we were kids, like 17 or something. I was [in South Africa] until I was about 20 and Ollie until he was seven, so he was back for the first time and we just kind of met by accident. We were friends for a good 10 years before we started working together, and that was very organic, the way that started. [In university] Ollie studied philosophy and I studied predominantly history of art and sociology. So we never intended to be photographers or artists or anything. It just happened to us.

When was the moment when the wheels started turning in this new direction?

We actually started working—it’s quite a convoluted story, but in the early ’90s, Benneton hired Tadao Ando to build what was like a bit of a bunker underneath a vineyard in northern Italy, just outside Venice. And they set up a place for Fabrica, and there’s a filmmaker called Godfrey Reggio who did films like “Powaqqatsi” and “Koyaanisqatsi” with Philip Glass, they made him the head, and he sent people around the world, recruiting. I was lucky enough to be invited out—young and broke in London—and the next thing: I landed up in Venice with access to all these facilities and started working on the magazine Colors.

So we started working like that. We were working with other people’s images, it was a social and political magazine but using photography a lot. We got increasingly frustrated with not being able to take the pictures, but also these pictures would arrive and you wouldn’t know who the person was, and the whole process felt wrong. So we remodeled the format: We’d make a small team, go to the place and embed ourselves in a community and make a thing, and that resulted in a book of ours called “Ghetto,” which took three years.

Was “Ghetto” your first project?

It actually wasn’t. Our first project was called “Trust” which is a book as well, and that was also about the photographic process. It started off with various degrees of unconsciousness, it ends with people under general anesthetic. It’s about the relationship between the photographer and the subject and how much power, what’s the flow of power. Somehow we’re always surprised by the fact that people agree to have their photograph taken.

I’ve never had the courage to say “Stop” when I see people with cameras around New York City photographing buskers or sites, and find myself in the background of the photo or video.

We are always pleasantly surprised by people saying “Stop.” It’s so invasive. Now, I mean, you’re being photographed by cameras everywhere. In fact, one of our most recent projects is in Russia; a few weeks ago we went—they’ve developed a new technique called “non-collaborative portraiture” in which they set up cameras—say, along traffic lights—in the street and if there’s a big demonstration, you’ll be obscured by other people. So the camera will capture that amount and the next camera captures that. By the end of that street, or if you would just walk through that door, it constructs a 3-D mask that you can move in space. It’s essentially a police portrait—front and side on—without you even knowing or doing anything. It’s pretty frightening. We photographed members of the Pussy Riot group and the then-opposition leader to Putin, who’s now been put in jail for three years. So, our subjects were our way of protesting the technology. But that’s going to come out next year.

Is this the “War Primer 2” debut in America?

It is. We only made 100 of them because they are so laborious. We literally hand-screen printed them. Each picture is stuck in by hand on top. And we sold them for $100 each, just because—it shouldn’t be a rarefied object.

That’s why you made it available for free, online?

Exactly.

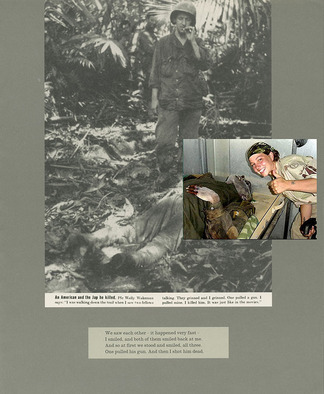

Some of the images you and Oliver chose in “War Primer 2” are very graphic. As we are increasingly exposed to violence and gore, and as it is depicted more frequently and accurately, do you think we become desensitized?

I don’t think we are desensitized to violent images. What’s more shocking is how sanitized the depiction of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq was. I mean, it was very hard to find a violent image unless you look very hard on the internet. Certainly in the mainstream news.

Does this censorship come from the government?

There’s a kind of relationship between—newspapers rely on advertisers to get their income. Advertisers wouldn’t deal with a picture of a mauled corpse on the cover. And I’m not saying that’s the sole reason, but compare the way these wars were depicted to the way Vietnam was depicted. It’s 50 years later and we’ve gone backwards in time. In the time of Larry Burrows—those images changed the course of history. People say part of the reason why the Vietnam War ended was because of those images. Whereas now, photographers are so controlled in war zones.

That’s a good point—as soon as you said “the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq,” I couldn’t visualize anything specific.

All you can think of is Abu Ghraib, right? That’s it. And that came from a proper soldier, not a professional photographer. That’s what the “War Primer” is really about. Brecht was looking at the way war was imaged. For instance, there’s a picture of a Liverpool bombing—that must have been a radical thing to see in the ’40s, an aerial view while it was being bombed—and we’ve superimposed over that an image of 9/11. That now is still very difficult to compute.

I was speaking to a good friend who lives in New York. He said there’s two moments in his life where his eyes and his brain could not function together. One was 9/11 and the other one was Hurricane Sandy. He was in the midst of it—it was too much to take in, if you know what I mean. I think there are things that we are unable to process as images.

Aside from reading the newspaper daily and keeping up with global political issues, what inspires your ideas for each new project?

Looking back at all these projects, there’s a line of thinking and politics. The strategies are very different. Everything looks different because because it’s appropriate for what we’re dealing with. What you just saw is very different from “Afterlife.” We’re not committed to one aesthetic strategy, but we’re always interrogating photography. It’s history and it’s future.

Since you and Oliver have done both in the past, do you feel more comfortable behind the camera or working with photos that have already been taken?

We just got to a point where it felt a little bit uncomfortable traveling around the world and taking pictures of people who had no idea about the political, economical, cultural power of that image once it’s out there in the world. That became increasingly uncomfortable for us. So I think that’s when we started looking at archives and material that was already out there. But we wouldn’t call ourselves archive artists—it’s much more of a collaborative process with the subjects rather than documentary, like a camera in a psychiatric hospital.

What are the benefits to working as a long-term duo? It’s rare in photography, but even in the bigger art world.

Traditionally when we do take pics, we use a camera that has a plate so you can both look and both frame. Now we hardly remember who took the actual picture. There’s something about being two people—photography people find it very uncomfortable because there’s this myth of the “photographer’s eye” and their sense of timing, and the duo undoes that, right? There’s also a sense of anonymity: I don’t own the work, Ollie doesn’t own the work, we kind of share that. I find it very liberating. When we get emails, we bounce the questions between us. After 15 years of working with somebody, you fill in the gaps. You know what’s going on in each other’s minds. Photography’s horribly lonely.

View Broomberg and Chanarin’s “War Primer 2” at the New Photography 2013 exhibition, which runs until 6 January 2014 at MoMA in New York. While only 100 copies of “War Primer 2” were produced, the digital edition is free and available to the public online, accompanied by critical essays. Also catch the duo’s other work, “Afterlife,” on view at the Death of a Cameraman exhibition at Apexart, which ends 26 October.

Portrait courtesy of the artists. Single page images © Adam Broomberg, Oliver Chanarin, 2013, courtesy MACK. Photographed book spreads © Adam Broomberg, Oliver Chanarin, 2013, courtesy MAPP