Adriana Kertzer: Favelization

Author of the upcoming e-book on the fetishization of favelas and Brazilian culture

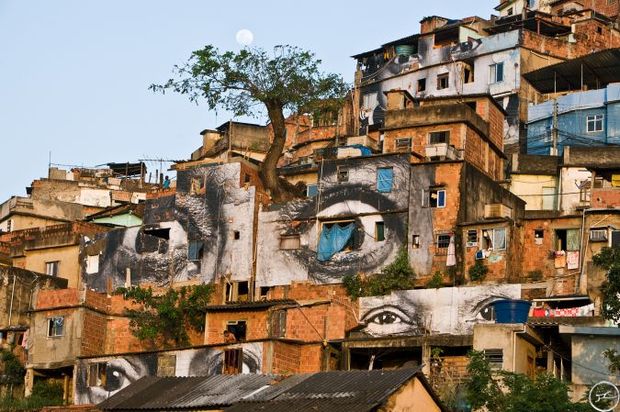

Plastic furniture ubiquitous at cheap botecos in Brazil made to look like they were riddled with bullets (and sold at high-design prices), a chair created from wood scraps that was inspired by discarded furniture designers once saw in a favela, couture dresses conceived with help from residents of a Brazilian slum: these are just a handful of examples of “Favelization.” It’s a term that Adriana Kertzer has named the movement of fashion and furniture designers, filmmakers and artists who are “misappropriating” symbols and stereotypes of the favela to make their products more appealing to non-Brazilians. Kertzer, a New York-based lawyer-turned-art-consultant, transformed her observations into a master’s thesis for Parsons that will now be getting wide release in the form of an e-book under the Smithsonian’s Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum’s imprint this month as part of its DesignFile series. We spoke with Kertzer about phenomenon and the complex political and social issues surrounding it.

How is favelization different than the “ghetto fabulous” concept—of us selling ghetto culture to other countries?

I have noticed one important difference. The aesthetics we regard as “ghetto fabulous” were created by and spread amongst the inhabitants of certain American neighborhoods. Certain “ghetto fabulous” trends then spread among other communities, eventually entering mainstream American and global culture. In the case of favelization, the trend began outside of the favelas and became popular outside Brazil first. Yes, you can argue that the aesthetics of favelized luxury objects were inspired by the favelas. However, the individuals creating and marketing favelized objects were not originally favelados [residents of the favela].

Now that favelization has had a few years to develop, has it been sold back to Brazilians?

You are absolutely right. As the São Paulo-based designer Paola Crosco stated at dinner this month, Brazilians need a critic outside of Brazil to say something is good first, then they will consider it. Upper-class Brazilians have always looked outside the country for new aesthetic trends; first to Europe and now to the United States. This dynamic has also been the case with favelization, which is now manifesting itself in Brazil as it has in Europe and the United States for years. An example is the Boate Vidigal, a nightclub in Porto Alegre. Its interior design attempts to replicate the aesthetics of Vidigal, a favela in Rio de Janeiro, and the nightclub’s target audience is upper-class Brazilians.

Have you observed favelization becoming more festishized as the World Cup and Olympics get closer?

Official logos, for example, do not reference the favelas. However, it is interesting to see how different promotional videos related to these events selectively include (or exclude) images of favelas.

You make it clear that you believe favelization is exploitative. How can an artist/designer/filmmaker proceed in a way that it is not?

That is the question I still struggle with. “Favelization” is a book that uses specific case studies to explore the dynamics of favelization and reveal similarities between this trend to other trends in history. As a design academic, it was not my intention to write a “guide” on how to favelize properly. My objective was to explore and reveal connections, similarities and potential problematic dynamics. As a design curator, I see examples of objects attached to fantastic storytelling everyday. I also know of incredible objects that deal with “national” themes. Perhaps the way to engage with any type of storytelling is to keep it genuine. But the responsibility for avoiding the exploitation of stereotypes does not lie solely with designers. Journalists, advertising executives, companies and consumers also need to avoid reducing great storytelling into simplistic generalizations.

How have the designers and artists whose work you use as examples reacted to your categorization of their works?

I don’t know yet. They all know about the project because I have requested images and image rights. Some designers might be a bit wary but recognize that having their work analyzed in such depth is important. Others might experience a deep sense of discomfort, perhaps because the style of design criticism I deploy is not as common in Brazil as it is in the United States. But at the end of the day, I hope the designers share my belief that Brazilian design will only assume a fuller role in design history once objects receive serious and sustained analysis.

What do you have lined up for 2014?

I am currently working on the exhibit “New Territories: Laboratories for Design, Craft and Art in Latin America” as a curatorial assistant at the Museum of Arts and Design in NY. I would like to see “Favelization” turn into an exhibit itself, curated by someone other than me! Later in the year I will begin working on an exhibit about the “MadMen” TV series and another titled “Fine Art Fabricators.” Another book? I would like to write about the re-branding of marijuana in the United States.

Favelization is officially released on 11 February 2014 and is available from Amazon and

iTunes.

Images used with permission of respective artists, designers and brands, courtesy of Favelization