Interview: Artist Hank Willis Thomas

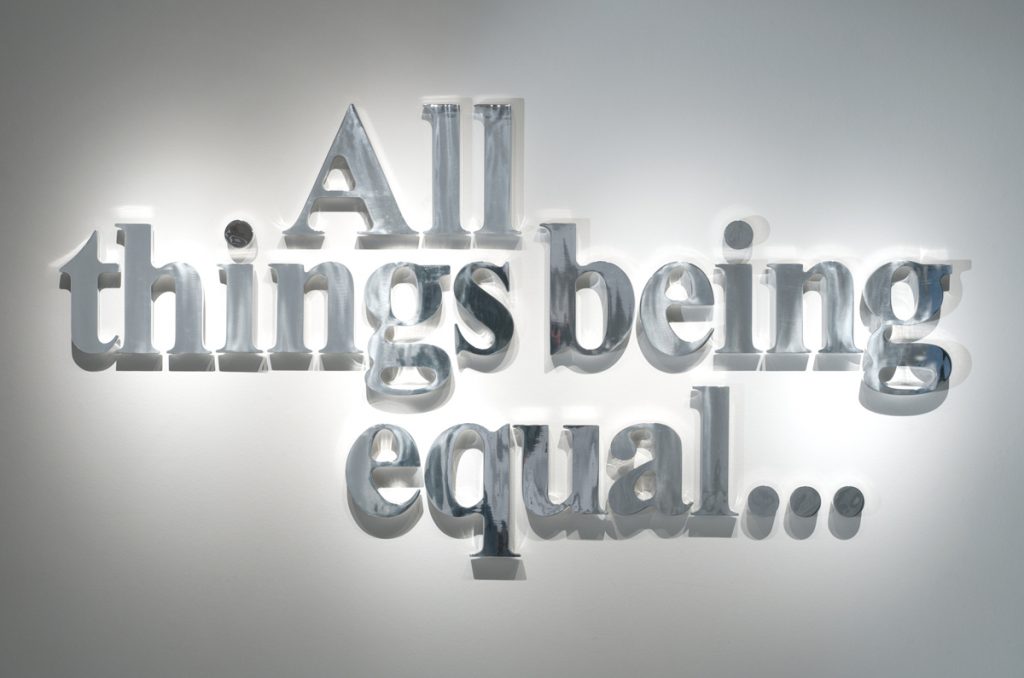

The prolific artist on his retrospective, “All Things Being Equal,” as it makes its final stop in Cincinnati

Black lives matter. While this chant began in 2013 as a response to the murder of teenager Trayvon Martin, it’s a sentiment steeped in the USA’s history and one that artist Hank Willis Thomas has been exploring for two decades. His work takes a careful look at the messages we intercept every day—from advertising to sports to art and beyond—and reconfigures it to expose some essential truths about ourselves, what we allow to influence us and who we are as a collective humanity.

Thomas may be someone who flies under the radar due to his quiet, humble nature, but his oeuvre speaks volumes about the way he views the world. And it’s not just limited to his personal output, which is collaborative in its realization but inspired by his own curiosities; Thomas is also the co-founder of For Freedoms, an organization for creative civic engagement, and the Wide Awakes, a super-current platform for community- and creativity-driven understanding of mobilization and participation.

Thomas’ work feels more relevant than ever, so we checked in with him about what has changed, and what has stayed the same throughout his 20 year career.

How has the way you think about things changed in the last six months, if at all?

I think there’s definitely a greater response and a greater resonance to the work that I’ve always been doing. My specific concern is, “Where do we go from here?” And I believe that peace and justice will prevail. I also think that this is a pretty frightening time when it comes to—I mean, look at what’s happening in Portland, where the show started. It’s a serious moment, and someone’s got to put an end to this in a positive way.

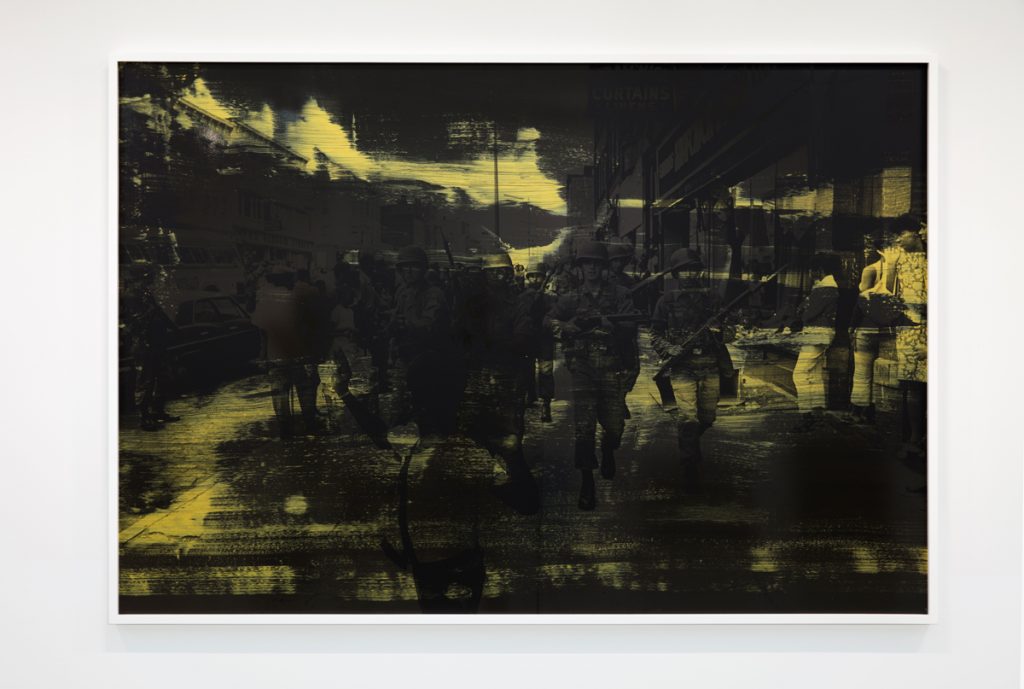

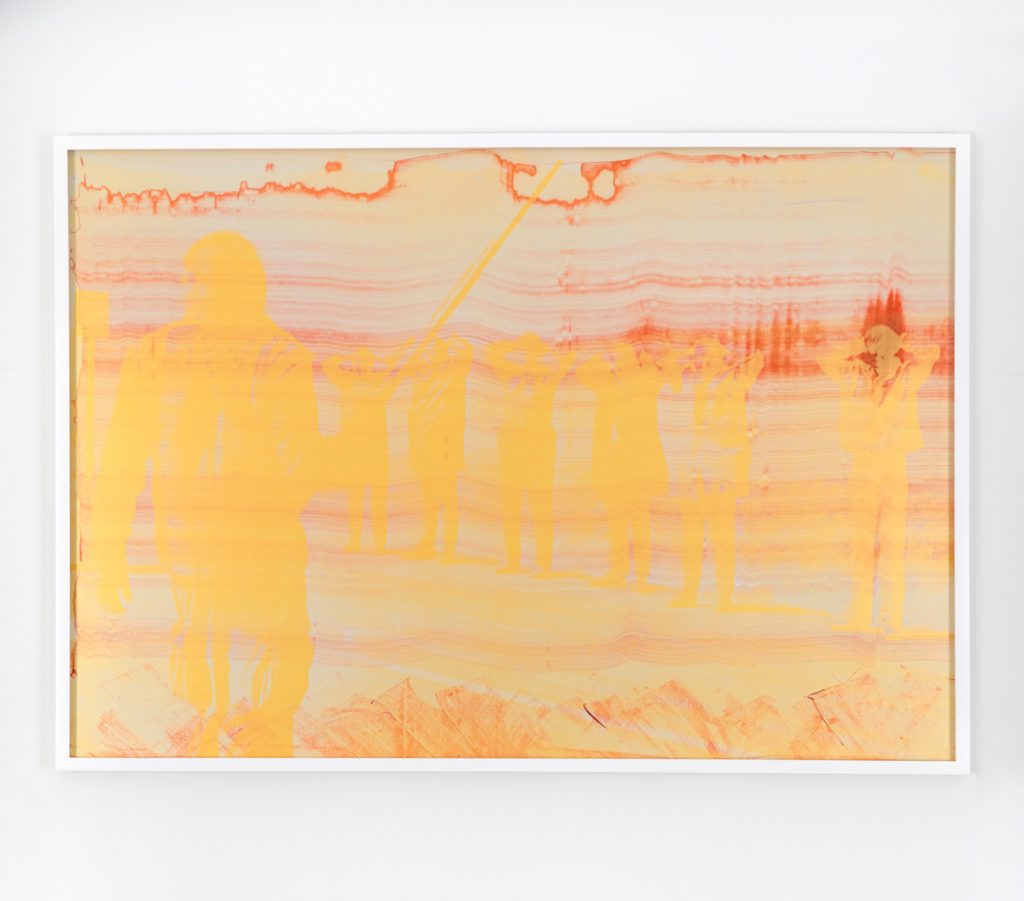

Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

Do you label your work as protest art?

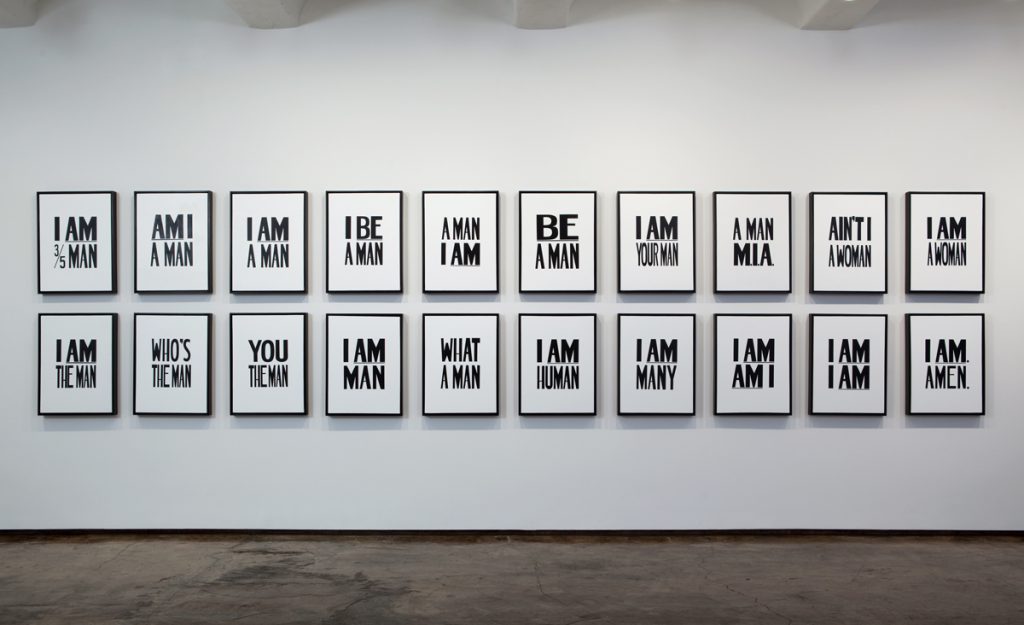

I don’t. I think it does highlight protest, it’s about protest, but all of it is not protest art. I’ve been looking at protests as a creative form of civic engagement and proactive advancement of society. For the past four years I’ve kind of reshaped the meaning of that work, which is largely around things that happened in the mid-20th century. So now 60 years later, those same images, those same stories being so relevant to oppression, there is that sense that history is repeating itself or at least that we haven’t learned our lesson.

How do you describe your work?

I think my work is very much my life. So it’s a product of my search, my quest for personhood. My quest for my own specific voice to be clear and to understand the world and make sense of it.

Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

What’s your process like?

I was always fascinated by the power of advertising to shape and influence our notions of what’s important, who’s important and who we want to be. And so for me, that has been the journey and it became more clear when I did the Unbranded series that I could look really critically at how advertising used prejudice to inform and shape our version of yourself through playing on our stereotypes and our need to be simple, clear and beautiful. And I wanted, more and more, to encourage myself and others to really engage deeply with the kind of, if not brainwashing, the potency of advertising and its ability to control our values through seductiveness.

You work as an artist, but you also have your ideas in other places, from fashion to billboards to museums.

Yeah, and I’m learning new mediums. It’s such a learning process; the world has changed so dramatically in the past six months that all options have to be on the table for us to really get through this carefully.

How do you stay “conceptual” when reality is so crazy?

One of the pieces in the show is “Art Imitates Ads/ Imitates Life.” That’s it, that’s all of it.

Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

How does your personal work differ from For Freedoms?

My studio practice is all about me, right. Even when I don’t do it all—all my work is collaborative—and For Freedoms and the Wide Awakes are ways to kind of more publicly collaborate, and people don’t presume that my voice is the leading voice and think that I’m the only one doing this work because in reality, there are thousands of artists doing similar work that inspired me and have inspired me. My studio practice is just in that continuum, so we’ve been doing exhibitions and billboards and town halls, collaborations with artists and organizations across the world as a way to stake a claim for artists and civic life, and to make our work collectively something that people can see as an alternative to the typical propaganda that is that we’ve grown used to in our society. Because we add creativity to political speech it actually opens up doors and online on how we actually might engage in legislation and political life.

So that has been pretty enlightening, to say the least. The generational levels of it, I don’t know, but like big dad and being not just me—I’m part of a legacy I would hope. And that will hopefully outlive me and live on for generations. And that the work that I make is speaking to someone else’s life in a very different way than it was when I made it. I didn’t conceive that my work might be something that someone 10 have 20 or 30 years ago might have to relate to and engage with it. It’s part of my own biography. It also changes the way that I think about myself, even as a citizen at this time.

What’s surprised you most about your career?

That somehow I’ve made a living doing it. I’ve just been following my dreams and trying to be genuine somehow, you know; I’ve been able to continue to do that for almost 20 years.

All Things Being Equal opens tomorrow at the Cincinnati Art Museum and runs through 8 November 2020.

Hero image “Public Enemy (II)” [variation with flash] (2017) by Hank Willis Thomas Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas