Interview: Artist Julie Mehretu on Radical Imagination

We speak with the illustrious MacArthur Fellow about her career, influences and her new American Express collaboration

Evidenced by this year’s career-spanning exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art (which began at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art), Julie Mehretu has established herself as one of the world’s most accomplished artists—and she’s only just getting started. Having already been named one of Time Magazine’s most influential people, in addition to having received a MacArthur Genius Grant, Mehretu is on an inspiring artistic trajectory. Most recently, along with the internationally acclaimed artist Kehinde Wiley, she collaborated with American Express on their reimagined Platinum Card design—available 20 January 2022. This year also marks the beginning of American Express’ multi-year commitment and partnership with the Studio Museum in Harlem, an institution recognized globally for advancing the work of visual artists from the African and Afro-Latinx communities through its artist-in-residence program, of which Mehretu is a graduate. We caught up with Mehretu during Miami Art Week 2021 to discuss radical imagination and how art can change the world.

Can you tell us a little bit about the development of your style and artistic voice, and how that plays into the way you produce your work?

It’s taken a long time. It’s really a slow process of developing a language, like a visual language that can really be something that works within the language of the history of abstraction, but also becomes something else and can be not necessarily brand new, but can deal with new content and built language to support something.

Within abstraction there’s a lot that I can communicate that’s visceral and felt, but that we don’t have language for

I think there’s a lot of clear events in the world that informed who I am and who we all are, that really informs how I make my work and how I think about my work. I work in abstraction because I think within abstraction there’s a lot that I can communicate that’s visceral and felt, but that we don’t have language for, that we don’t have words for. That’s my approach to making the paintings.

What do you believe your defining moment has been thus far? When did you know you were an artist? When did you start calling yourself an artist?

I was always taking art classes, always making art, all my life, since I was very, very young. It’s something I always wanted to do but I didn’t know that you could have a life making art until I was older. I grew up in the Midwest. We didn’t have contemporary art museums. We didn’t have what you have in big cities. Now you do. They’re all over. We have an amazing museum in my hometown but we didn’t when I was growing up, so we didn’t have contemporary artists. We only had historic artists to refer to. And so, I always was making art, always wanted to, but I didn’t really think of myself as a practicing artist… I guess that’s not true. I guess I’ve always thought of myself as an artist but it wasn’t until later that I thought I could actually build a livelihood.

I came up in the late ’90s. It was after you had this intense, queer and BIPOC push toward a different form of identity politics. My generation ere the beneficiaries of the work that generation before us had really pushed.

A lot of the gatekeepers in the art world have been—and continue to be—older white men. Can you tell us about some of the obstacles that you faced getting to where you’re at, how you overcame them and what the art world can do to make those things better for the next generation or the next group of emerging artists?

I think things are really different than when I started and when I was making work, but I think even when I was starting and making work things were very different than the generations before. The generations before, they were finally getting their due. When artists were making and starting off in the ’60s and in the ’50s when you had the explosion of American modernism, a lot of Black artists were not necessarily included as part of the canon or part of that historical narrative, although they were making art. I think you’re finally seeing their impact. Many different artists who’ve been working, finally now you’re seeing it change and how they’re regarded in the canon.

I think for me, I came up in the late ’90s and it was after Act Up. It was after you had this intense, queer and BIPOC push toward a different form of identity politics. My generation came out after that. We were the beneficiaries of the work that generation before us had really pushed.

Who were some of the artists who helped you find direction or pushed you forward?

That list is long and complicated and it goes back 500 years. I think the really important artists to me now have always been really important to me—artists like David Hammonds, Adrian Piper was really important to me when I was younger. And then, I was also interested in painters like Cy Twombly. It was a very big mix. Joe Mitchell was someone who was interesting to me. Weirdly, Elizabeth Murray was another artist. These are just different examples, and even if I found some of that work complicated, I was interested in the possibility of what they were pushing as artists.

You were the recipient of a MacArthur fellow. What was that like?

Shocking. It was so shocking. I’ll never forget where I was when I got the phone call. I was in Minneapolis, there with my young son and my former wife and she was preparing for an exhibition. While she was preparing for an exhibition, we were staying at a person’s house who was a trustee of where she was showing. I was in this bedroom office of theirs and I get this call from the MacArthur, and they wanted to take a photo there in Minneapolis.

They just sent someone over to find you?

Take a photo that day. Yeah.

Can you tell us a little bit about what happened next?

I think what it did is what has happened continually through my career which is to get a little bit of support and that support propels work and propels the capability of being able to really think creatively and push more stuff. I can tell you I wouldn’t be able to do what I’m doing without having had immense support in the past and that’s what MacArthur offered. Put a bunch of wind in the sails and it allowed me to really push and make, and not have to worry about resources. I had a small family and it came at a great time.

What’s one of the main messages you try to get across in your work and what do you you hope people will take away from your art?

Just the possibilities of radical imaginative thought, and that we can imagine collective other worlds. That we can think differently about the world we live in. And hopefully, you’ll have a visceral, physical reaction or a response to the painting that’s somewhat transformative. You can’t have transformation without a radical imagination.

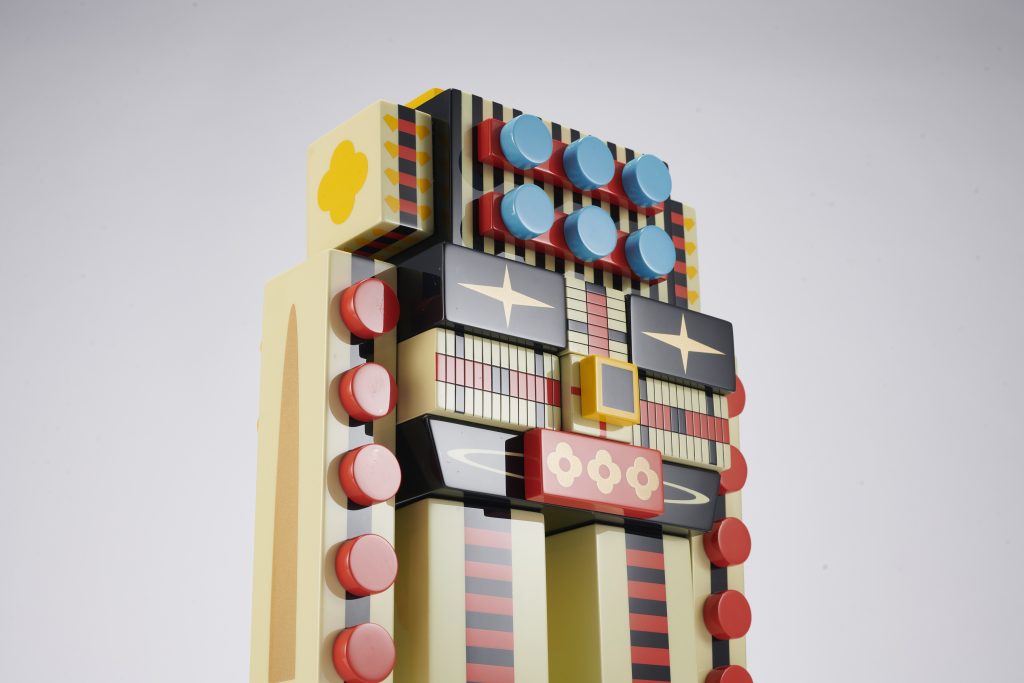

Tell us about your collaboration with AMEX and how that came together. What was your thinking behind the reimagined platinum card?

I’ve been thinking about agents wanting to do things for artists who are trying to shift culture—I think all artists are doing that, to be honest, but their support of Black artists and BIPOC artists, queer artists and artists who have traditionally been considered marginalized in the center core of your historic art world. I think you see a big change in what makes up that dynamic and AMEX has really been a champion of that. I am honored that they came to me. It became an interesting kind of proposal and I have to say I’m really struck by their support of the Studio Museum and other programs. Their discussion with me came about through that, as well. They offered a good amount of support to my non-profit, which I co-founded with two other collaborators. That was also very amazing, to be able to have certain significant support for that. So, it became a really interesting collaborative conversation.

Going from the MacArthur to being named one of Time’s most influential people, what’s next?

I’m working on a bunch of different projects, different ideas, exploring different materials, working in different materials. But more than anything it’s really trying to stay inside the work, evolve the work—making paintings that I can’t imagine right now and blow myself away with something else. It feels like a long period of time and a nice career, but it’s only 20-something years, so there’s a whole life of work to be done. There are a lot of artists who lived a lot longer and made a lot more work, so I have a lot of catching up to do.

Hero image by Bryan Bedder/Getty Images for American Express