A Conversation with Composer Cliff Martinez

The brains behind the film music for Solaris, Drive and Spring Breakers on his newest bloody project with Steven Soderbergh and more

A Q&A with film score composer Cliff Martinez at Moogfest this year attracted a mix of curious festival attendees and die-hard fans—many of whom cared much more for Martinez’s dark, ambient scores than the actual movie plots. The regular Steven Soderbergh collaborator (“Sex, Lies and Videotape,” “Traffic,” and “Solaris”) has reached even more prominence lately since scoring critically acclaimed films such as Nicolas Winding Refn’s “Drive” and Harmony Korine’s “Spring Breakers.” Martinez, a soft-spoken and charming speaker, was surprisingly upfront about where he gets his ideas and how he executes them. Budding film score composers, take note: Martinez uses software synths like Omnisphere and u-he, arranging in Ableton Live, but calls himself a preset guy. However, you probably don’t own a gamelan metallophone or 17 baritone steel drums from Trinidad—the latter of which are prominently featured on the “Solaris” soundtrack, which Martinez cites as his all-time favorite score: “I wish I could roll out of bed every day and write another ‘Solaris.'”

When you’re a drummer looking at a drum machine, you’re looking at your own obsolescence.

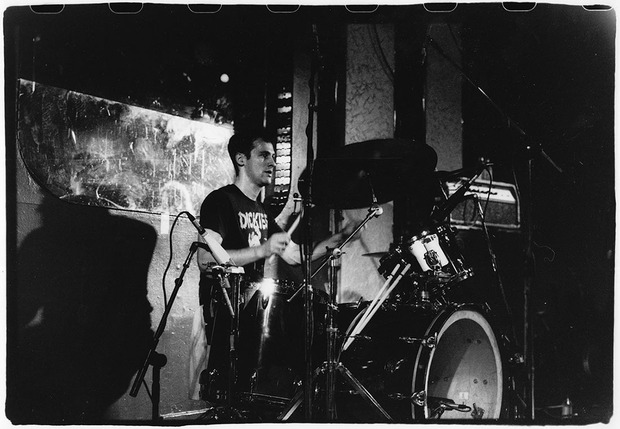

The Bronx born, Columbus, Ohio-raised musician moved out to LA in his early 20s, and dove headfirst into the Californian punk scene. There he drummed for different bands, most notably for the Red Hot Chili Pepper’s first two albums. Martinez also encountered the new “gizmos” that were making their way into recording studios, like the E-mu Emulator and SP-12 drum machine and sampler. “When you’re a drummer looking at a drum machine, you’re looking at your own obsolescence,” he shared with the audience, chuckling. He was captivated by the new possibilities that electronic and computer-generated music offered and adopted these as his main instruments—and the way Martinez played with them would eventually lead to his first scoring gig, an episode of Pee-wee’s “Playhouse.” (The children’s show has been a breeding ground for others like Mark Mothersbaugh, Danny Elfman and The Residents).

Martinez also shared that the temp track is potentially the composer’s greatest enemy. Directors will often choose “temporary” music to edit the film to, which can also give the composer a sense of the mood for different scenes. But the unintended consequence is that directors will get attached after living with the music for a few months—and expect something very similar from the composer. Martinez actually lost one particular fight; after Refn was insistent on using M-83’s “Sister, Pt. 1,” Martinez included an arrangement for it in the film “Only God Forgives.” The musical accompaniment to the much-discussed fight scene in the same film, however, is Martinez’s own masterpiece, influenced by a mix of “Ennio Morricone, Philip Glass and Goblin.” We spoke with Martinez after the seminar to learn more behind-the-scene stories of life as a Hollywood composer.

You mentioned earlier that you cringe and couldn’t watch your movies after finishing the scores. When you go to see movies in theaters, do you get distracted by other people’s scores?

Pop music, you listen to the singer; in a film, you listen to the dialogue. You look at the images and maybe the third level of what you’re aware of is the sound.

People often say to me, “Your score in such-and-such a film was so good that

I didn’t even notice there was any music.” And I never know if that’s a compliment—I guess? But usually I know what that means. If I see a film that really, really works, and I’m really moved by it, I don’t remember the score that well. Pop music, you listen to the singer; in a film, you listen to the dialogue. You look at the images and maybe the third level of what you’re aware of is the sound—the music and the sound effects. So I think music in a film kind of operates a little more subliminal—it usually isn’t in the spotlight—I think most of the good film scores I’ve heard, I’m not that aware of it.

Some music [however] does both—it draws a lot of attention to itself and it functions really well in the film. Like Thomas Newman is a guy that I always go, “Wow, that guy is really inventive.” But everything that he does is in support of the dialogue and the images.

Does that make the idea of a “standalone soundtrack” or selling soundtracks separately from the film on a CD sort of an oxymoron?

Yes, and that’s why I don’t listen to film soundtracks [on their own]—and I include my own music in that category. Its role is to accompany something else and oftentimes, I don’t feel like it holds up as a standalone experience. Personally, I like to just experience the music in the film, because that’s how I appreciate what the guy did. Because you can write a great score, but if it doesn’t work with the picture, you didn’t do a good job.

Since you’re your own boss, how do you figure out how many hours you’re going to work that day?

The deadline, usually—paranoia is a very good propeller. The fear of not delivering on time keeps me on some kind of a schedule. But yeah, being self-employed is difficult. And when I’m not working, I’m a complete couch potato.

Do you think your composition style has changed over the past 25 or so years of work?

When the “Drive” soundtrack was so successful, I had been scratching my head and trying to figure out what the recipe is, what is it that made it so popular. To me, it sounded like I’d been doing the same thing since 1989 with “Sex, Lies and Videotape”—this ambient style, that’s kind of dark but it’s really, really simple. It’s atmospheric and textural, and not that musical. There was something about the simplicity—one riff, one idea, it’s catchy and it’s super repetitive. I’ve always liked simple, repetitive things. It didn’t seem that I’d come that far [with “Drive”]. So I think I’m kind of the electronic, ambient musician that I was in 1989, and perhaps I’ve just tweaked it, developed it and added a few more dimensions to it.

While we might take them for granted now, you’ve definitely been a pioneer for bringing ambient, electronic music film scores to mainstream films.

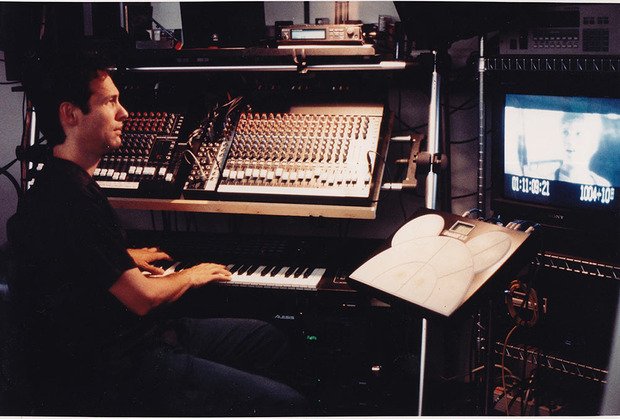

Look how much evolution there was from the 1930s to 1950s to now. I think the biggest evolution has been in music making technology; I went through three-inch and five-inch floppies to SyQuest drives to the ADAT to the DA-88 to no tape machine to QuickTime Movie.

And did you self-teach Ableton Live?

I’m pretty much a self-taught knucklehead. I have to read the manual—I know that’s archaic. I use all this complex software at a pretty primitive level. I use a lot of presets.

But you know, a lot of the synthesis principles are the same no matter what plug-in you open.

What was it like collaborating with Skrillex for “Spring Breakers”?

Well, I didn’t see him too much—he’s pretty busy. I saw him twice. There wasn’t a whole lot of us-in-the-same-room type of collaboration. When I first met him, we talked about the idea of “Scary Monsters And Nice Sprites” as a theme for the film. So for four or five pieces, I took his theme and kind of lent some atmospheric stuff—that was one form of collaboration. There were a couple things where we sent some body parts to each other; he sent me a beat and I took it and did something with it and he would add to that. And then there was kind of like a division—beat-driven scenes, he did; and if it was something more interior or psychological, I did it.

Was it an easier score because you split the workload?

I think on average, films usually have a little bit less than half their running time [of music]—an hour and a half movie might have 40 minutes of music. But Spring Breakers was almost wall-to-wall, there were like 23 songs. I did—I think—50 minutes of music and Skrillex did a ton of music. So it wasn’t any easier; a normal film would be 45 minutes of music and I did 50. It was easier in that Harmony [Korine] was pretty easy to please; somehow we seemed to get in a groove right away. But in terms of musical real estate, there was still a ton of music to write. It was just like music everywhere; there’s only like a couple scenes that had no music.

You mentioned your work for the upcoming HBO film “The Normal Heart.” What else are you currently involved in?

Steven Soderbergh has a period medical drama called “The Knick”—it’s an abbreviation for Knickerbocker, a hospital. It’s based on the first big wave of immigration in New York City and the kind of beginning of [modern] surgery—coming out of barbershops and becoming a legitimate medical procedure. And it’s really bloody. [laughs]

And what kind of sound are you digging up to go along with these visuals?

It’s interesting—the series is a very lovingly crafted recreation of 1900s America in New York. And the music is pure Kraftwerk-tinker toy-electronic-buzzy-synth music. It was Steven’s idea and first I thought, “Really? You really don’t want to acknowledge the period in the music at all? In fact, you want to go in the opposite direction?”

It reminds me of Sofia Coppola’s “Marie Antoinette”—the more contemporary soundtrack is such a contrast to 18th-century Versailles, but it kind of made the story more relatable, rather than a distant historical event.

I think that was the idea. When I talked to the producer, in so many words I thought he was saying, there’s a risk—period dramas tend to not be too cool with a younger audience. So they hired a really old person to sound like a young person, I guess, or sound contemporary. [laughs]

Is there anything else you’re currently working on?

I’m working on a top secret video game—it’s a sequel; there’s three and this is the fourth.

When is it going to be out?

Probably like 10 years from now! The gestation period for video games seems to go on forever.

Hear Martinez’s score in “The Normal Heart,” starring Julia Roberts and Mark Ruffalo, a new film based on Larry Kramer’s 1985 Tony Award-winning play about the HIV-AIDS crisis in New York City during the ’80s. It premieres on HBO on 25 May 2014. The Cinemax series “The Knick” featuring Clive Owen is slated to premiere this summer.

Moogfest photo by Nara Shin, all other images courtesy of Cliff Martinez