Interview: Recording Artist Ezra Furman

Surveying the sound of the indie singer-songwriter, from a Bandcamp release to the Sex Education soundtrack

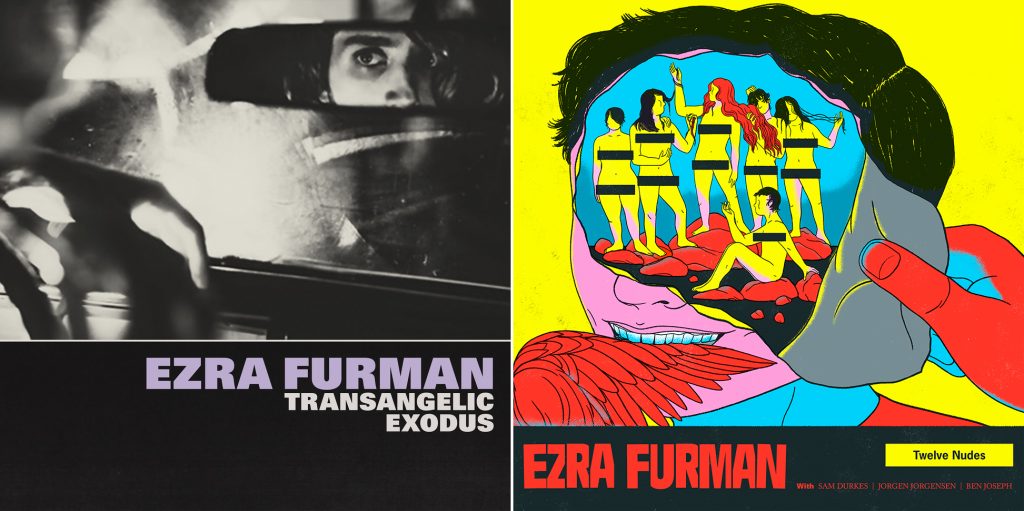

With the recently released Bandcamp-exclusive album To Them We’ll Always Be Freaks, literary rocker Ezra Furman shares rarities and “reject recordings” from behind the scenes of 2018’s urgent, erudite and experimental LP, Transangelic Exodus. A lot has happened between those releases: a catchy, substantive soundtrack for the hit Netflix series Sex Education, the boisterous brilliance of 2019’s Twelve Nudes, and the release of a book on Lou Reed’s iconic album Transformer, included.

Furman has much to say through her music, to the benefit of all listeners. It’s the combination of melody and storytelling—with elements from Judaism, queer culture and political rallying cries informing narratives—that sets Furman apart. From release to release, Furman’s orchestrations oscillate from raw and raucous to comforting and whimsical. Always, experience carries through her entrancing voice. And each album, including those made as Ezra Furman & the Harpoons, makes for a great adventure when listened to from start to finish. We spoke with Furman about sonic transformations, songwriting and the value of live performance.

Why did you release To Them We’ll Always Be Freaks on Bandcamp instead of other platforms?

We wanted to invite people to pay what they wanted for it. The release happened because we were losing so much income since our live shows got canceled due to the pandemic, and we need to keep ourselves afloat somehow. Bandcamp makes it easy to set prices. Sometimes I feel like we should release everything on Bandcamp. Most platforms make it really hard for us to get paid much for our recordings. So basically: remember to buy things from artists you like, if possible. [All proceeds from To Them We’ll Always Be Freak will be distributed between Furman’s band and touring crew.]

There’s a sound leap between Transangelic Exodus and Twelve Nudes. Can you talk about that shift—and how you embraced the punk soundscape?

Punk rock was the first music I loved as my own, the first music that didn’t come to me from my parents and which I actually liked. It was my doorway into music culture. It’s a little surprising that I hadn’t made this punk-y of a record before. I knew it would happen eventually. Though I’m always listening to some punk, it was after spending many many months making Transangelic Exodus that I got a heavy craving for that type of music, both because it was contrastingly quick and simple to make and play, and because it was angrier—as angry as the daily news had started to make me feel. We also recorded with a new engineer/producer (Trevor Brooks) and in a new studio (Coyote Hearing in Oakland, CA), and with a whole different mood around the sessions. More easygoing, less brow-furrowing about how to make it sound original. I don’t consider either approach superior, but after one it’s nice to have a dose of the other.

In your songwriting process, how you go about translating emotion, and emotional force, into these meticulously crafted songs?

That would take a long time to explain, if it even could be explained. It feels like there’s a different way in to writing a song each time I do it. Which is to say, I have no reliable process. Except trying and failing and trying and failing, over and over, and then finding what came out of all those attempts that could become something effective.

Have other art forms infused/influenced what you make?

Yes they have. Particularly poetry, prose and Jewish liturgy and sacred texts. Those things influence/filter it in ways that are hard to describe. I am fascinated by words and texts and I study how they do what they do. And a lot of those tactics can be transferred to songs. Sometimes it’s more conscious, sometimes less so. I really love genre-defying writing like Anne Carson, David Shields, Renata Adler.

Do you feel like the storytelling and song traditions of Judaism have helped shape you as an artist?

Oh, hell yeah. The book of Tehillim (aka Psalms) has been a particular influence. So has Shmot (aka Exodus). I intended, with Transangelic Exodus, to draw on the idea of midrash—the rabbinic and pre-rabbinic tradition of expanding on the Biblical text, filling in its gaps imaginatively. The album is my midrash on Exodus. There’s even a piece of the daily morning prayers at the end of our song “God Lifts Up the Lowly.” My Judaism gives me access to a whole world, a whole universe of references and attitudes that haven’t been drawn on all that much in popular song—even including gospel music, because that’s only one flavor of traditional religious reference. There’s so much in my ancestral tradition that feeds right into my artistic obsessions.

There is a real relationship between me and my audience, and if I never see them in real life I run the risk of forgetting who I’m doing this stuff for

Can you talk about the value of live performance? And does live performance turn the songs you’ve recorded into something else?

I think of live shows as taking my dogs out for a walk. The songs are dogs. They need to go out and get their exercise, and so do I. They’ll become weird under-developed “inside dogs” otherwise—it does happen to the songs we never play live. But more than that, it’s important for me to understand and personally see what our music means to people. There is a real relationship between me and my audience, and if I never see them in real life I run the risk of forgetting who I’m doing this stuff for. Not everyone thinks of doing music this way, but I don’t consider it as something I do for myself. I do it my own way, and I don’t put too much value on ideas of what people want from me. But in the end I think of art as a gift from artists to strangers. Though we the givers get so much out of it as well. Anyway, I love live shows so much. Plus we don’t make much money from other things. I hope they can start happening again soon.

How was the process of bringing together the Sex Education soundtrack different from bringing together other albums of yours?

I am having trouble answering this question. It was totally different. Emotionally and logistically. Doing something as part of someone else’s artwork/entertainment, rather than just as my own, feels completely different. I very much want to be of service. Also, we’re kind of auditioning each song for inclusion, because they don’t use everything we record for them. So it’s a bit of a mind-fuck. But the final outcome is wonderful to see. A show with its heart in the right place and which so many people love, and then our music is right in there at its big moments. It’s a joy.

What do you think is the role of social media for recording artists today?

Like all tools of marketing, it’s useful and it’s a distraction. It’s so useful that it’s very easy to forget that it has nothing to do with why people are or should be interested in us. It’s a flyer. It’s a very addictive and potentially compelling flyer. But if you’re working on flyers all the time instead of on your real work, you might have a problem. You might not be doing your best as an artist.

I cherish the queer community, and the characterization of my work as queer culture or queer art or whatever it is

Do you think that your music—and the way it channels your identity, fears and passions—positions you as an ambassador for the queer community?

This is a complex situation you are pointing toward. I know I offer comfort to and solidarity with many queers, as other queer artists have long done for me. But a communal ambassador? That’s not territory I want to get into. I work for the embassy of my own spirit, and I’m only ambassador to anyone who cares to listen. Still, I cherish the queer community, and the characterization of my work as queer culture or queer art or whatever it is. I’m proud to be a queer, and although I don’t represent anyone and no one else represents me, I do wear these appellations proudly; lightly, but with honor.

Can you share how you ended up penning the foreword for the Art Brut reissue of Bang Bang Rock & Roll?

Oh boy, the story goes back to 2009. Art Brut’s Eddie Argos had a side project band called Everybody Was in the French Resistance… Now! They did a showcase with us (my old band Ezra Furman & the Harpoons) at South-by-Southwest because they thought we must be super-famous because they heard us on the radio in Los Angeles. Not the case. Anyway, we met and got along well, and encountered each other on tour and at festivals a few times over the years, kinda became friends. Lo and behold, Eddie knows I’m a rabid Art Brut fan and he’s got the decency to ask me to write their liner notes for the reissue of their first album, a record that changed my life and deeply informed my own music. I still can’t believe I got to do it. I don’t remember what I wrote; I should pick up a copy.

What was your process for writing the Lou Reed’s Transformer book? How did it differ from writing songs—or an album’s worth of songs?

A friend pointed out to me that there was an open call for submissions to the 33&1/3 series. At first I was skeptical that I could contribute anything, but I was reading a Lou Reed biography at the time and had just written a little piece on gender and rock’n’roll for the Guardian. So my mind got whirring and I made my proposal. I was a bit amazed that they accepted it. But it was a solid idea. So any time I was off tour I would go to cafes and write, write, write. I talked with friends a lot about the ideas in the book too, which was very helpful. But it was totally different than writing songs. You get to, and have to, explain yourself. You can’t just gesture at feelings and images like in songs. But the songs I was writing at the time—which became our record Transangelic Exodus—both informed and were informed by the book.

Hero image courtesy of Jessica Lehrman