Laurel Braitman Reads Pets’ Minds

The author of “Animal Madness” explores the psychology of animals and explains how they are just as much individuals as humans are

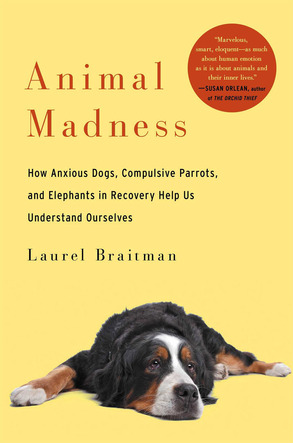

Senior TED fellow and science historian Laurel Braitman delivered one of the most engaging talks at TED’s 2014 conference. Her topic? Animal psychology and the emotional spectrum of pets. Braitman has studied the history of science for years—most recently as a PhD student at MIT—and through that lens, atop years of research with domestic animals, she uncovers insight into their emotions, how they affect our pets and ultimately parallel our own behavioral thinking. We recently sat down with Braitman to talk about her new book, “Animal Madness,” published by Simon & Schuster.

Evan Orensten: If I had to summarize your book in one sentence, I’d say “Animals have feelings, too.” In your TED talk you talked about your family’s donkey—tell us how he affected you.

Laurel Braitman: My donkey was the first extremely difficult and extremely charming animal I fell in love with. I don’t know if you feel this way, but in my life, sometimes the creatures who are the most difficult to love stretch us the most. Particularly when you’re trying to make a creature feel better who’s struggling with mental illness or some sort of emotional distress. You really have to plumb all avenues open to figure out how to help another creature because you can’t ask them.

I think the whole field of psychotherapy is based on this idea that we don’t know how we feel and it takes some time to figure that out or put words on it. That is difficult when we are dealing with another animal because there’s no real words we can get to. That said, I think with really careful observation and knowing an individual animal well you can, with time, really understand what’s bothering them—what their triggers are. Maybe you put together their individual history if they were a rescue animal, and you figure out what might have sent them down the path to madness and maybe the beginnings of a therapeutic plan to help them feel better.

EO: How did you come into the topic of animal sanity?

I got into this because my ex-husband and I adopted a Bernese Mountain Dog when I was just starting graduate school. The dog’s anxiety for the first six months was quite reasonable and then about six months in, his behavior became extreme. It began to erode. For example, we lived on the fourth floor of a brownstone in Washington, D.C. and one day he’d been left alone for just a few hours—he pushed the window air conditioning unit out of the way, he chewed the metal screen and jumped out of our house. And he survived.

Were these drugs going to work for him in the same way that they work for us? And if so, how do we know?

EO: That sounds traumatic.

LB: I didn’t know what to do. I’d grown up on a ranch with animals—including disturbed donkeys—but the dogs when I was growing up were always fine. He had to go to the vet hospital for a while and I asked the chief veterinarian, “What should we do?” He gave us a prescription for Valium and Prozac and told us to move to a first floor apartment. I got really curious: Were these drugs going to work for him in the same way that they work for us? And if so, how do we know? And how do these drugs get into pet clinics? How would I know when they were working for him? And as I said, I was just starting grad school in history and the anthropology of science.

EO: Did the drugs help your dog with his anxiety?

LB: The Valium really helped him. He had extreme thunderstorm anxiety in addition to separation anxiety and a number of other things. The Valium really helped with his thunderstorm fear. The Prozac did not help him, but I’ve since met lots of dogs that the Prozac has helped and other creatures—particularly a lot of great apes.

I think ideally what the drugs do (like they do in people) is they pause the anxiety or fear or compulsion long enough for you to also start other forms of therapy, whether it’s getting into a safe situation or getting out a relationship that’s traumatizing or hurting you, starting to exercise, finding a great therapist, doing behavior therapy, whatever it is. Sometimes those drugs give you a break. I think that’s really true with other animals, too.

I started to put together a history of roughly the last 150 years of human thinking about animal insanity and what I found that it’s almost a perfect mirror of how we understood ourselves and the unhinged human mind.

EO: So all of this got you thinking…

LBI started doing some literature searches and I couldn’t find out how this happened, so I started calling around and talking to neuroscientists and psychotherapists and a few psychologists. I felt I was touching the tip of an iceberg that would be really interesting. And so I started to put together a history of roughly the last 150 years of human thinking about animal insanity; I found that it’s almost a perfect mirror of how we understood ourselves and the unhinged human mind.

Everything from the first antipsychotics, like Thorazine, to how we think of developmental disorders and what happens if your mother rejects you or is unkind to you—like we learned from baby monkeys in the 1950s. So this long trail of animals, from whales to gorillas to cats to beagles, had really helped us and in some ways martyred themselves so that humans could better understand our own minds and emotional states. I just fell in love again and again with all of these people who were helping animals feel better.

EO: I find some of our behavior toward our pets abusive. Dyeing their hair, dressing them up like little kids in a pageant. And the more serious ways: putting them into non-natural environments, not being aware of their needs. It’s no wonder that some animals need therapy, but even in the professional animal care community you don’t see many people that know or talk about it.

LB: No, and it can sound crazy when you talk about bringing your dog to a therapist. One thing that helped my dog was developing a very strict daily schedule. He was a little like Rain Man; if anything changed, he would go haywire. That meant someone had to be home by 5PM, so I would leave work and had to explain to people at work that my dog will lose it if I’m not home by 5:30. I’m not sure if they really believed me.

The one place he wouldn’t freak out—and I think this is very common for people with dogs with separation anxiety—is in the car. So even if I needed to leave the house for five hours, if I put him in the car, he was fine. He wouldn’t freak out at all. And I think people can be very judge-y about people leaving animals in the car—I mean for good reason, if it’s hot or they don’t have water, but as long as it’s safe and they’re not going to get overheated and they have air and everything they need, it’s OK.

We should look at a bunch of dolphins and say that one’s kind of an idiot, that one is really smart, that dolphin is really playful. It is anthropomorphic, but it’s reasonable.

EO: What’s the most interesting thing you’ve come to realize?

LB: We tend to think about people as individuals, like we might say John is into ice cream and Tom is an anxious flyer. I tend to get anxious, but only before public speaking, but I love rollercoasters. Then we turn around and say shih tzus are aggressive, or chows are aggressive, and grizzly bears are ferocious, and poodles are smart or dolphins are really smart. I would really like to change people’s ideas of animals at a species level. We should look at a bunch of dolphins and say that one’s kind of an idiot, that one is really smart, that dolphin is really playful. It is anthropomorphic, but it’s reasonable. Why would we be the only animals to have personal preferences and personalities? And a mental illness is really a way to get at that because you can have two dogs come from the same litter, live in the same house, and one can develop a completely debilitating phobia of the vacuum cleaner and the other one is totally fine.

By healing other creatures, we can heal ourselves. Every time you cheer up a dog it’s really hard not to cheer up yourself.

“Animal Madness” is available on Amazon for $21.

Images courtesy of Laurel Braitman