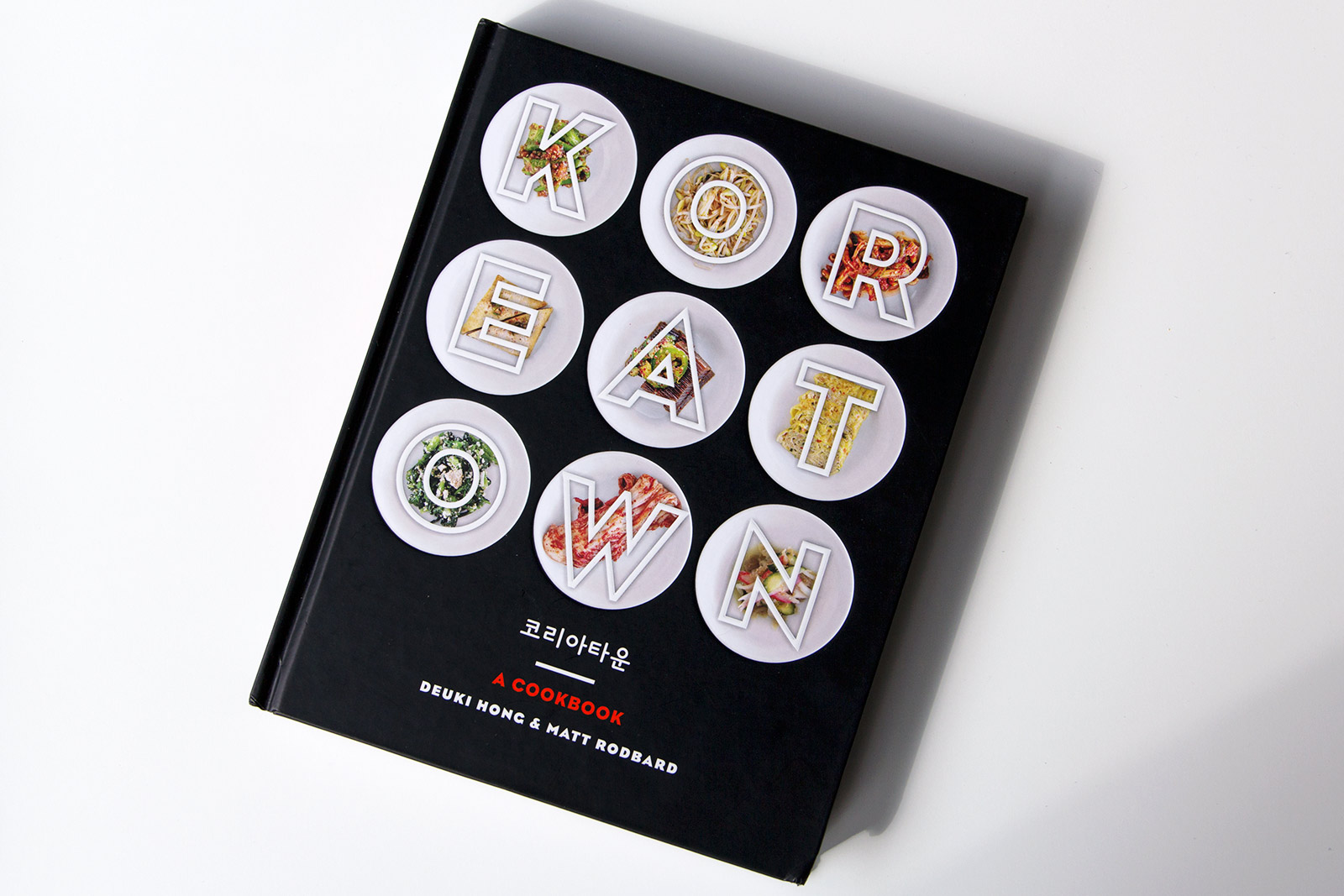

Koreatown: A Cookbook

Getting the lowdown on Korean food and culture, beyond BBQ

The paradox of Koreatown for someone like me, who calls Seoul home outside of NYC: you avoid it as long as you can—save for the occasional trip to H Mart for their affordable bulk kimchi. Yet once that inherent craving for hard-to-cook-yourself dishes like samgyetang or naengmyun strikes, I find myself once again armed with low expectations, waiting in a long line to be seated (and it doesn’t matter which restaurant on 32nd Street, as they have nearly identical menus), yelling at friends over the din, lamenting the outrageous prices and mediocre flavors, all the while gobbling down the endless banchan, or complimentary side dishes. It never tastes like home.

This love/hate relationship with K-town(s) is expounded upon in Deuki Hong’s intro to “Koreatown: A Cookbook.” The chef—who trained under Jean Georges Vongerichten, David Chang and Aaron Sanchez and now at the Manhattan branch of insanely popular BBQ chain Kang Ho Dong Baekjeong—knew that for many non-Koreans, barbecue is their first taste of the funky, mysterious world of Korean food but there’s so much that lies beyond the fire.

“Our cookbook is written in the perspective of someone who’s lived here,” says Hong, who co-wrote with food writer Matt Rodbard, currently Contributing Editor at Food Republic. “It’s not one of those ‘101 Best Korean Recipes’ or ‘Korean Cooking Made Simple’ books. It’s really two kids from New York, who have very different backgrounds but we both love Korean food. And we just wanted to tell the story—not only of Koreatown, New York, but everywhere. We travel to Minnesota, Houston, all these places that you don’t think Koreatowns or even Koreans even exist, and we learned a lot from that.”

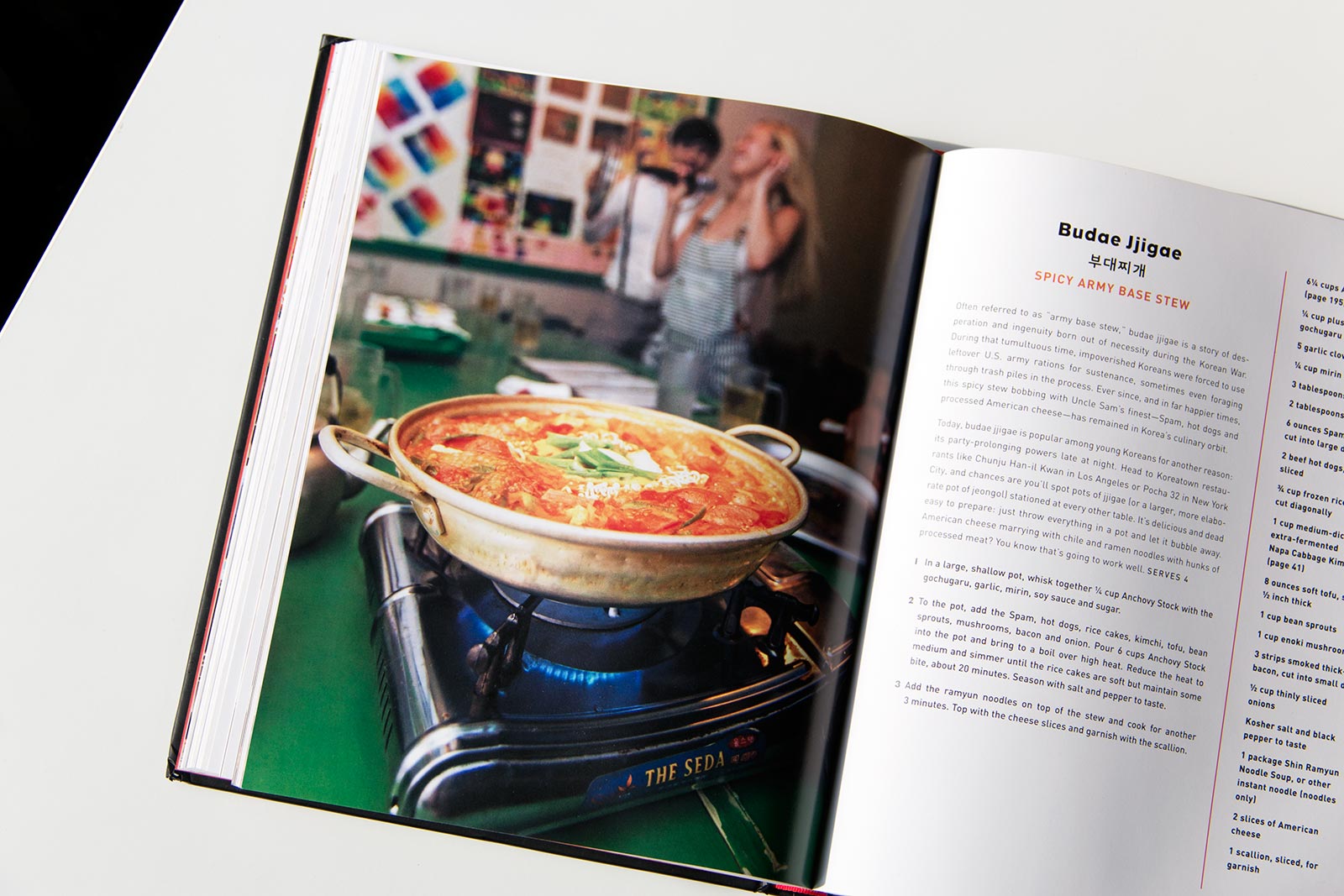

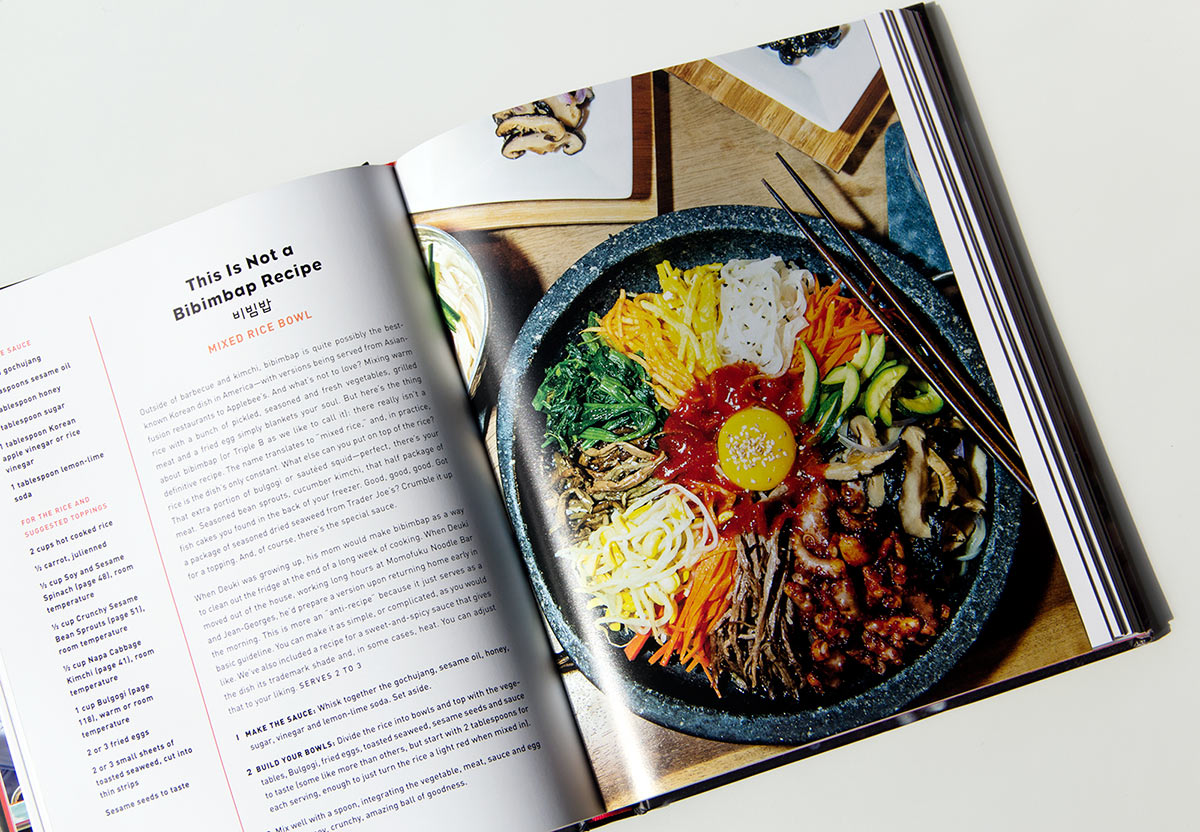

All the classic recipes are here, some tweaked a bit to accommodate contemporary pantries and tastes, like taken-for-granted japchae (clear sweet potato noodles), miyeokguk (birthday seaweed soup) and hearty stews like gamjatang (a spicy pork neck and potato stew that’s a favorite hangover cure). Peppered between are interviews and anecdotes, guest recipes from restaurants like Mission Chinese Food and The Meatball Shop, plus two in-depth chapters covering drinks and “drinking food”—a significant part of Korean culture. From the best way to make Shin Ramyun instant noodles (it can’t reach its true potential without additional ingredients: one egg and a slice of cheese) to why two-year-olds need to eat kalbi off the bone, “Koreatown” so far has been one of the most accessible and entertaining tomes on Korean cuisine we’ve come across. Hong confesses that his picture of the future is simple: that years down the road, Korean food will join Italian, Chinese, Japanese and Thai as one of the frontrunner suggestions to, “What do you want for dinner?”

Unlike a lot of cookbooks that focus on one country’s cuisine, “Koreatown” steers clear of fetishizing the foreign. In lieu of artificial, angelic lighting and pristine plating (Korean food, they acknowledge, is more fiercely in-your-face than it is Instagram-pretty), Sam Horine photographs, for example, an auntie server lifting a pot of steaming kimchi stew or karaoke singers in the background. His documentary-style approach captures the energy and community of the kitchens, restaurants and culture and along with the rest of the book, Korean food’s complexity (no shortcut to making beef bone noodle soup from oxtail bones) and even flaws are embraced tightly here. David Chang of Momofuku, Hong’s former boss, sums it up best in the interview inside: “Korean food is a weird thing, man. It’s just a highly neurotic cuisine. There’s no other food that is loved and hated at the same time by the people who adore it the most.”

Koreatown: A Cookbook releases next week online and in bookstores. Also peep the events calendar at the book’s official website.

Images by Cool Hunting