Pioneering Immersive Artist Lucio Fontana at LA’s Hauser & Wirth

Timeless experiential artworks from the avant-garde Italian artist

Installation art isn’t new, though it’s perhaps been garnering more attention over the past few decades, as technology rapidly improves and expands. Light and Space artists have been concerned with the transformation of physical environments since the 1960s, tapping into a centuries-old practice through inventive uses of glass, neon lighting, and various other techniques and materials. One could be inclined to include Lucio Fontana in that movement, but his work mostly predates it. Fontana built his first immersive work in 1948 and passed away in 1968, as the Light and Space movement was truly solidifying.

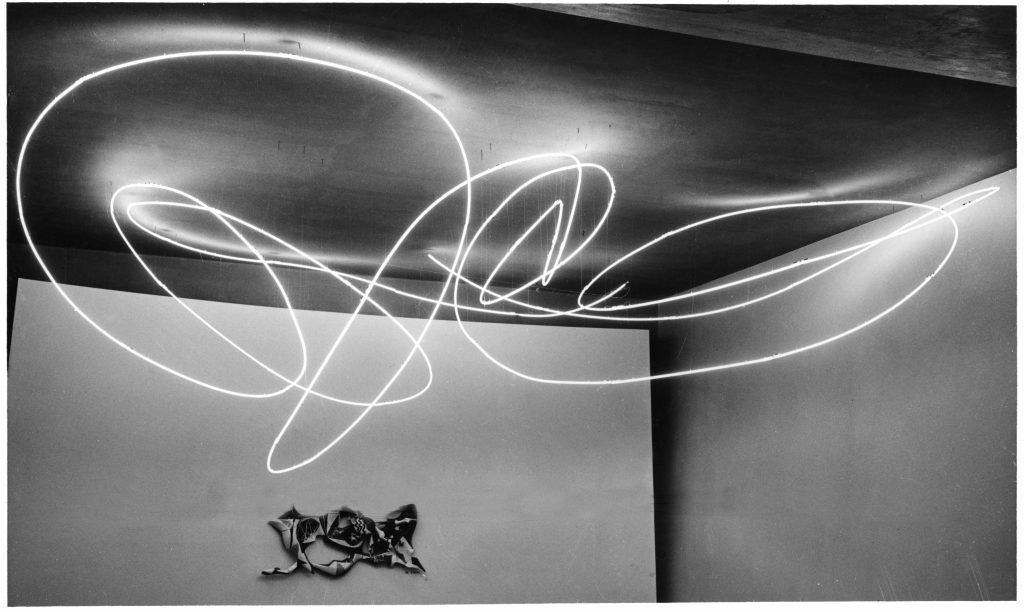

A selection of Fontana’s ahead-of-their-time works will be on display at LA’s Hauser & Wirth later this month, as part of a curator talk with Luca Massimo Barbero. These immersive works are detailed reconstructions of the artist’s creations from 1948 to 1968—works that were designed to be destroyed at the end of their exhibition. On display will be like “Ambiente spaziale a luce nera” (1949), a piece that used wooden lamps to create black light that cast paper-mâché as fluorescent objects, as well as “Ambiente spaziale” (1966) which was a space that had small holes punched in the walls and ceiling to create the illusion of a glowing dotted line square.

These pieces revolve around technology and may appear like contemporary works, but when they first debuted they were confusing for many viewers. “Fontana really was a scandal then,” explains Barbero, the curator of the broader exhibition, too. “People were saying he wasn’t an artist. They couldn’t understand that he was building the spaces for an experience. That’s very contemporary.”

According to Barbero, Fontana set off in this direction in the 1940s after spending time in Argentina with a “very futuristic bunch of young kids” who fomented ideas about technology in his mind. “Fontana writes about the power of neon light, radio, radars, and TV,” Barbero says, alluding to how he prescribed this notion to art, saying “we don’t need to sculpt anymore.” Fontana was suggesting that, in the post-atomic, post-WWII world, physical space was the area to broadcast thought, not objects you place in space. “The dimensions of the world changed,” Barbero says.

What Fontana was doing in the 1940s revolutionized the experience of “viewing” art through inventive uses of light and space that had never been seen before. “This is the first time, after WWII, where the viewer became a performer,” Barbero says. “The visitor wasn’t a visitor… [Fontana] was saying forget about objects: just walk with me in the space.”

The Los Angeles exhibition of Fontana’s works captures this feeling of timelessness—even as many works approach the 60-year mark. But Barbero reminds us that we need to keep in mind that historical context when encountering these works. “We have to be simple and humble enough to understand that we’re looking at someone pioneering,” he explains. “We have to understand we are looking at a primer, something really radical… Fontana is really showing us the incredible future viewer. We’re looking at the roots of the future.”

Lucio Fontana’s Walking the Space: Spatial Environments, 1948 – 1968 opens 13 February and runs through 12 April at Hauser & Wirth in LA.

Images courtesy of Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milano