Tribeca Film Festival 2016 Premieres ‘Magnus’

Director Benjamin Rhee on his documentary about the #1 ranked chess player in the world, Magnus Carlsen

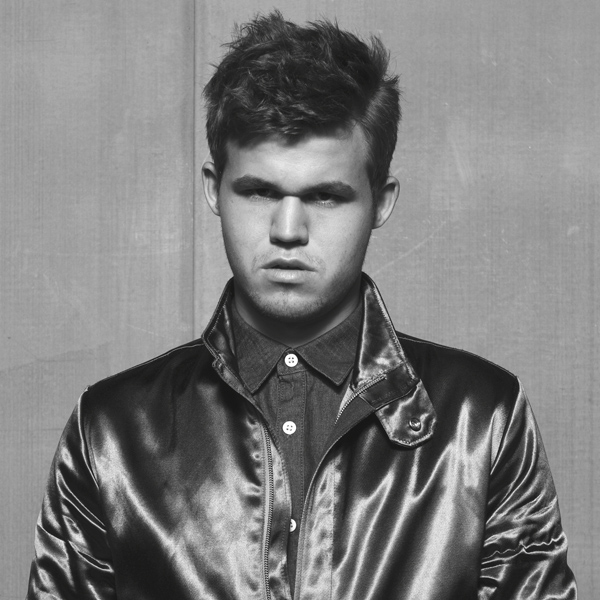

For more than a millennia, the game of chess has engaged and seized the greatest minds in the world. The game moves beyond the 16 pieces and the 64-square board, much of it a mental battle taking place within—and picking up many victims along the way. Bobby Fischer was the great chess player who never became the hero America wanted, his genius overshadowed by his paranoia and erratic behavior. This perhaps explains the fervor around Magnus Carlsen, the 25-year-old Norwegian chess player who’s captured not only records—ranked number one in the world since 2011 and the highest rated player in history—but he’s also captured hearts with his humanity and approachability.

Genius is a difficult story to tell, especially on a subject as complex (and for some, dry) as chess, but the new documentary “Magnus” (having its world premiere at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival) hits many right notes. “Magnus” follows Carlsen’s attempt to become the World Chess Champion back in 2013—a goal he set at age 13, when he became an international grandmaster. Keeping interviews with “talking heads,” omnipresent voiceovers and insider chess lingo to the bare minimum, director Benjamin Rhee takes viewers on an emotional journey—and as close to Carlsen’s mind as they might ever be. We sat down with Rhee to learn more about the making of “Magnus.” (Spoiler alert: he wins the World Chess Championship).

Interestingly, you’re a fellow Norwegian, and also the same age as Magnus. Did that help him open up in unique ways during the shooting?

I think that was a huge advantage for me because there were some Academy Award-winning directors that wanted to film Magnus, and that put some high pressure on him. If you have a hot shot director that’s going to make a big, big movie about you, you can’t focus that much on chess. I’m young, I made a lot of short documentaries but not any feature-length; this is my first feature-length. I think Magnus would have been intimidated having a really famous director following him around. When I came along, I wasn’t any celebrity director. I think that gave me access.

The great thing about starting to make a short documentary is that you never know where it will end up. “Magnus” started as a five-minute project. If I told Magnus, I would like to make a feature-length documentary about you, he would say, “I don’t have the time.” But when we start with baby-steps, it’s so much easier to get full access. That’s what I do now, because you never know where the story will end up. And some of my favorite documentaries, like “Hoop Dreams,” they started out as a small project.

What was it like being in Chennai, India, watching and waiting for Magnus’ every move during the World Chess Championship?

It was total chaos. There were so many cameramen, and they were not that well-organized. In a way, that was an advantage for the film because chess is an introverted sport, and film is an extroverted medium. The way we convey what Magnus is feeling—we can use the press people to show the chaos. And actually, what we do in the film to convey this idea: at Game One, you see the glass wall.

It felt like they were in a zoo.

Yes, like being in a zoo. We head back to the other side of the glass wall. The camera is at the point of view from the photographers. Then we go back inside, to where Magnus is. That’s Game One and you can hear the noise from a distance. At Game Two, we slowly make the glass wall disappear a bit, sound-wise. So this is all about psychology. At Game Three, we hear even more and you go into Magnus’ head, because he was playing badly.

It was dramatic, especially the moments when his hands were trembling and dropping pieces onto the board.

I did hours and hours of interviews with Magnus, of how he was feeling there. We had a version where we played this out on voiceover, but then you didn’t feel anything as an audience. You were just hearing what he was saying about him being nervous. So then we took what he was saying, and converted it to cinema. And then the photographers, the media became a visual metaphor for his inner demons. So we used sound and editing techniques to hopefully make you feel the tension Magnus was feeling at that chair.

While the film focuses on Viswanathan Anand’s use of computer programs to prepare for the World Chess Championship, it didn’t seem to detail how Magnus uses computer programs in training—which is, these days, an unofficial requirement to play at the competitive level. Is it misleading to say that Magnus is led largely by intuition and gut feeling?

Everyone uses computers, because there are so many different ways of using computers. Magnus uses computers as a reference; it’s so easy to search for games and see the patterns. Anand uses computers to find opponents’ weaknesses and uses much more complex computer programs and analyzing systems to find the exact, best opening preparations—like a tool, a weapon. You could make a whole movie about that, the difference. What Magnus really tries to do is to kind of get out of preparation, so it can be man against man. And his strength is to slowly put pressure on the opponent so at the end, the opponent cracks.

During the time you were with Magnus, through the World Chess Championship and afterwards—did you perceive a noticeable change?

Absolutely, absolutely. Magnus has never shared, or celebrated his victories before. So him running into the pool and screaming like that, that’s something he has never done. There’s been so much pressure on Magnus. It’s extremely emotional—but again, Magnus is Magnus, you know. Before he can scream and celebrate, he had to process.

It was so funny [when he won] because I was behind the camera and going up to film Magnus, and I was expecting him to start crying. Because this has been his life goal and there are hundreds of millions of people playing chess. It’s just so difficult to become the World Chess Champion. And when he finally achieves it: he just sits down and he’s not satisfied with the last game. He drew the last game, and won the whole championship, but he wasn’t satisfied with the last game. Magnus has told me, he hasn’t played a single game where he’s totally satisfied with it. He’s so critical. There’s always something he could have done better. That’s one of my favorite scenes, and something that’s really special about documentaries. We couldn’t end a fictional film in that way; it would have been rewritten. Because it actually happened, we could include it. It’s really anti-climatic, you know. You couldn’t find a better anti-climax, Magnus being unsatisfied. We wanted to include it because it says so much about Magnus’ personality. He has to process before he can celebrate.

How has your own life changed after working on this project, watching Magnus in person and in the editing room for so long?

I can compare it to… I have eaten my favorite meal every day for three years, for breakfast, lunch and dinner. And it feels a bit like, I’ve eaten it a bit too much now. I really enjoy watching the film with an audience, but for me to watch it with just a few people, it’s horrible. When you see things so many times—I’ve probably seen it 3000 times—I wake up in the morning and I hear the exact quotes from the film in my head, like, “It’s man against man now and that’s bad news for Anand.” Like how a song gets in your head, but the whole film is stuck in my head.

This must be how Magnus thinks about chess, all the time.

Yes, I think so. I can relate much better to him now, after making this film. [laughs]

“Magnus” has two screenings remaining, today and 23 April (tickets and film info available online). Rhee expressed hope that the documentary will have a theatrical release around the time Carlsen returns to New York City this November, to defend his World Chess Championship title once more.

Images courtesy of the film