The Mexic-Arte Museum Taps Into Underserved Artistic Histories

Resurfacing cultural richness provided by Mexican artists and encouraging visitors to look beyond the bubble

The Western world predominantly controls art institutions, most of which are lacquered with a strong history of colonialism and conquerors with little-to-no regard for the oppressed. This limited perspective catalyzed Mexic-Arte Museum founders Sylvia Orozco, Sam Coronado and Pio Pulido to create an institution “dedicated to cultural enrichment and education through the collection, preservation, and presentation of traditional and contemporary Mexican, Latinx, and Latin American art and culture to promote dialogue and develop an understanding for visitors of all ages.” This purpose, outlined in their mission statement, now acts as a foundation for the community in Austin, Texas.

Their entrance into the Austin art world began in the fall of 1984, on Día de los Muertos. 35 years later, the museum’s curator, Rebecca Gomez, addresses the current state of affairs by making clear that “because the museum has government- and city-funding, we are not able to make a statement on the president’s political views of border control and immigration, but we do provide an exhibition space for artists to make their statements. I think by us showing certain pieces, it shows solidarity for the people affected in this ongoing issue.”

She adds that for this year’s Day of the Dead parade, there will be “an exhibition… with two artists who are doing an installation on these disappearing children; the children that go into detention centers and are being detained at the border. Normally, we have very festive floats. This year is going to be maybe more somber with this very serious subject.”

She offers contrast, though—explaining the dichotomy of their existence. “Incidentally enough, on this past bond election for the city, we were on the ballot for funding to renovate the facilities and the voters passed that resolution. All of downtown Austin is disappearing, and we are the last on our block, left in this space.” Their victory underscores the importance of this institution in the community and the overarching threats of gentrification.

As for programming, for the first time ever, drawings from the museum’s collection are exhibited collectively in Crossing the Line: Drawings from the Mexic-Arte Museum Permanent Collection. Artwork from museum co-founders is displayed alongside artists Arturo Rivera, Andreí Renteria, Andrew Anderson, and Felipe Reyes. Each pushes the boundaries of drawing to reinvent the medium’s possibilities.

In Rivera’s drawing “Air” (2003), a mother figure is suspended, weightless, anchored only by the child in her waist pocket. Her hair is skewed to the right of the canvas, creating movement in a limited space. The hands of the mother are separated as her face rests in a moment of anguish. This is contrasted by the boy’s hands firmly clutching a stick. The composition draws stark resemblance to “Medea about to kill her children” (1838) by Eugene Delacroix and alludes to the legend of La Llorona. The use of charcoal and sanguine pigment draws out the nuanced symbolism of bloodshed and blood ties highlighted against the dark grit of the drawing’s charcoal base.

Felipe Reyes‘ exploration of drawing in his color-rich portrait “Figure with Black Dress Looking Inward” (1988) is subject to its erasure. The body is encapsulated and divided from the yellow background as horizontal lines blur the details of the woman’s face and body. The feeling of dehumanization is palpable when viewing the work. Here, the figure is reduced to a trace, shadowed by the lines of smeared pastels. It contrasts well with Andrew Anderson’s performance work “Ouroboros” (2018), where the artist traces a line on the walls of the gallery and then erases the charcoal marking. In this work, the line is explored and rejected, revisiting a childlike state of drawing on the walls and problematizing the aesthetics of the white cube. The documentation of the performance marks a transmission of drawing into the medium of video. The eraser and charcoal chunk are displayed in vitrines, representing them as works of sculpture.

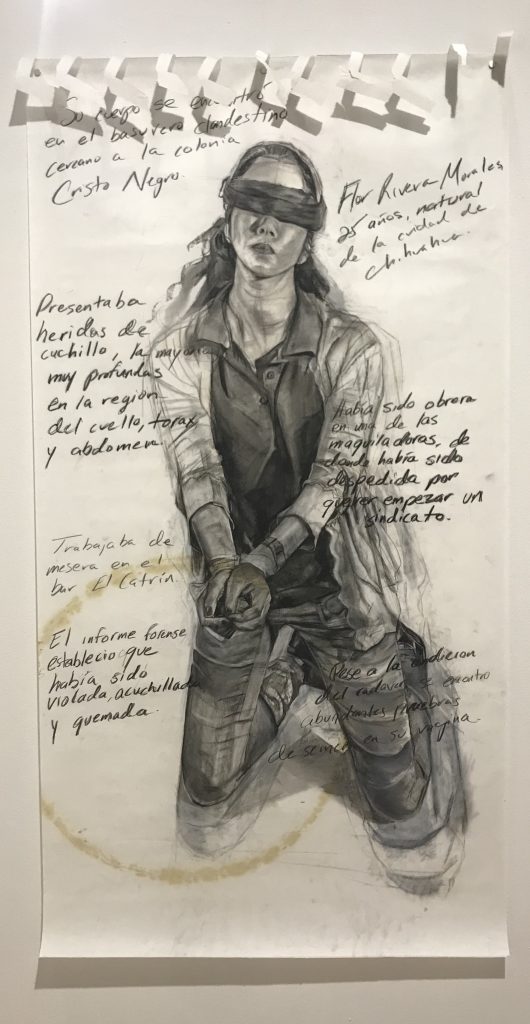

Andreí Renteria’s “Drawing Fringes: Flor Rivera Morale” (2017) depicts a Mexican woman bound and blindfolded. Renteria’s work tells the story of a young women’s violent murder, presenting her body in a state similar to how it was found. The work embodies the materiality of drawing, as the “fringed” paper torn from the pad’s spiral-binding reflect a crime report torn off of a detective’s notepad. The use of Lithographic crayon on vellum in Renteria’s drawing puts this work in conversation with Willem De Kooning’s door-sized drawing “Women” (1965); De Kooning similarly depicts a ravaged women objectified in a powerless position on vellum. The use of vellum illuminates the suspension and slippages, allowing for this style of drawing. Renteria calls attention to the crisis surrounding missing women in Mexico and the violence that corresponds. Gomez explains, “This is a huge problem that occurs along the border and especially in the El Paso Juarez region, but then nobody wants to address it or talk about it.”

This institution also offers a testament to the rapid development of historic downtown Austin. “This city was divided using the highway system from east to west, with the white population on the west and people of color on the east side,” Gomez says. “With this tech boom, there is gentrification happening all over. They are moving into spaces where people of color exist and are pushing them out.” Further, with Facebook and Google creating offices in Austin, the skyline is unrecognizable when compared to five years prior.

Discussing the role of art in this gentrification, Gomez explains, “We have these artists that are trying to make it, and survive here in Austin. It’s very much a challenge to have not only space from them to work, but also have space for them to exhibit their work. Some of these institutions that are here in town are facing displacement because they can’t afford the rent. So it’s kind of this odd cycle where this boom in the city is supporting the arts, but at the same time, it’s killing the arts. It’s a strange anomaly.”

It’s kind of this odd cycle where this boom in the city is supporting the arts, but at the same time, it’s killing the arts

Complementing the drawing exhibition, “La Huella Magistral: Homage to Master Printmakers” features works from 19 artists. Each pays tribute to a master printmaker who mentored, taught, or inspired them and then contributes artwork in their mentor’s preferred medium or recognizable style. Poli Marichal’s print “Comrades en la Marcha” (2017) explores issues of segregation and racism in its propaganda style. The signs and bodies melt together creating a mass of forms for the central figure to arise from, depicting a similar political stance of revolution and protest as seen in Jaime Montiel’s “One Social Change Begins” (2017). This work advocates for education and against oppression, using a quote from Caesar Chaves to ground the work.

Complementing the drawing exhibition, “La Huella Magistral: Homage to Master Printmakers” features works from 19 artists. Each pays tribute to a master printmaker who mentored, taught, or inspired them and then contributes artwork in their mentor’s preferred medium or recognizable style. Poli Marichal’s print “Comrades en la Marcha” (2017) explores issues of segregation and racism in its propaganda style. The signs and bodies melt together creating a mass of forms for the central figure to arise from, depicting a similar political stance of revolution and protest as seen in Jaime Montiel’s “One Social Change Begins” (2017). This work advocates for education and against oppression, using a quote from Caesar Chaves to ground the work.

“Alegoria Goyesca” (2017) by René H. Arceo interpolates “The Allegory of the Industry” (1805) by Francisco Goya. In the work of Goya, he explores a series of four allegories depicting scientific and economic progress. The exploration of industrial and scientific development is represented through the transmission of culture and community. The theme of development is shown as the family cooks together, demonstrating the preservation of traditions.

It’s crucial that visitors view these works and support institutions with missions that focus beyond traditional Western ideals. Thanks to Mexic-Arte Museum’s dedication to allowing these artists and works to speak, a sense of compassion and knowledge is experienced. These two exhibitions are open now through 2 June and provide a precursor for the upcoming festival and celebration of the museum’s 35th anniversary.

Images courtesy of Mexic-Arte Museum