Mark Dorf’s Alternate Landscapes

The photographer on perceiving surroundings with our digital state of mind

Whether behind a camera or behind a computer screen, Mark Dorf finds himself returning to the subject matter of landscapes—both the natural and the digitally construed. “I tend to travel a lot to find these remote areas that feel as though they’re untouched, but, of course, they are—every landscape is affected by the hand of man,” the Louisville, Kentucky-raised and now Brooklyn-based photographer tells CH. Dorf also lends his own hand, digitally altering landscapes and creating an alternate universe in which skies coexist alongside bright color gradients, wooded trees and sunlit clearings, next to 3D-rendered apparitions of a house, a couch or data visualizations. His surprisingly serene artworks (uncommon in the world of digital media) ask for more than just a Facebook or Instagram like; they stir up questions about what it means to have previewed the Grand Canyon, for example, hundreds of times through Photoshopped and VSCO-filtered images online before even stepping foot in Arizona.

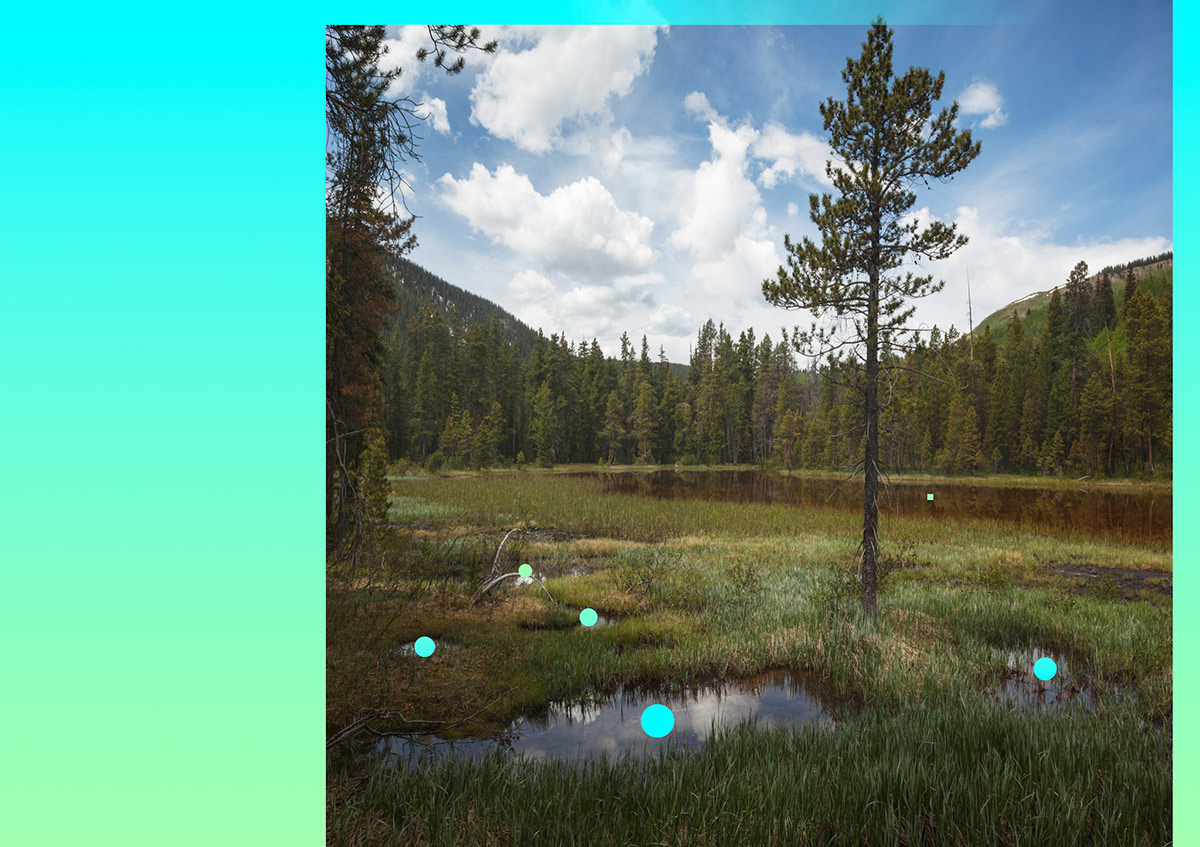

While the word “escape” is used often during travel, Dorf recognizes that we’ve developed personal filters (stemming from our dependency on the internet and technology to navigate the every day, as he puts it) that result in searching for the expected, rather than discovering the unexpected. We chatted with the artist to learn more about two of his recent series, “Emergence” and “//_PATH,” and on seeing and perceiving surroundings through the eyes of technology.

What do you think attracts you so much to these remote landscapes?

I grew up in Louisville and it’s a good sized city. It wasn’t like I was out in the Boonies, but the Kentucky landscape is really beautiful. The Appalachian Mountains in the east and then down southwest, Paducah. There’s also lakes and of course, rolling farmlands. But as far as my attraction to the landscape, I was never a kid growing up that just plopped down in front of the television. We had this beautiful park in Louisville, designed by Frederick Olmsted, the same guy who did Central Park. It’s massive. I was always outside, scrambling around, climbing trees. That sense of adventure, it’s never really left me. I’m always trying to figure out where I can go, what I can see, what I can climb still.

So you’ve got some really roughed up knees.

Yeah! When I was a kid I was always, always getting hurt. But also, the landscape is sort of where I feel the most comfortable, and not like in a sort of hippie-dippy way, but you know, I find ease in sort of the loneliness that’s involved with it. “Loneliness” might be the wrong word, but you do feel singular out there when you’re so far removed from a major urban center. And I find that to be easing to my brain.

It allows me to think clearly and really listen to things and see things specifically. And living in large urban centers like New York and Louisville, and tiny ones like Hudson, it gives you this sort of spectrum of contrast that I find really important. It allows me to make realizations better than I do when I’m living in a highly constructed urban environment.

When you are in the Redwood Forests, for example, shooting photos, are you alone?

I like to do everything myself and for the most part, when I am shooting, I am alone. Sometimes I’ll take little expeditions with friends and stuff, and we’ll go out and look, but most of the time when we do that, I don’t even take photos—I like to go and see these places with my eyeballs first, you know, to really examine the landscape, see what it feels like rather than hide behind a lens.

I’m not the photographer that carries the camera with him all the time and captures every single moment. I’m much more about capturing very specifically what I want that perfectly reflects the vision that I have for the piece itself.

For the “Path” series, how long were you in the forest?

That was actually one of my shorter bodies of work; I was only out there for around two weeks. I flew into San Francisco and then we drove up the Pacific Coastal Highway and we were just kind of going around there. We got more or less to Oregon and then turned around. That body of work was really different for a lot of reasons, actually. I knew what I wanted to put into the landscape, and the tools I wanted to use, like 3D renderings, these sort of collage effects, 3D scans, and stuff like that. But usually I know exactly what it’s going to look like, where this thing is going to go, how it’s going to interject into the landscape, but in this sense I was much looser. I relaxed a lot in this body of work.

I knew that they were all going to be central compositions. And after shooting a while, I understood that I wanted a certain sort of quality of mysterious light—a sort of God-like light. And then later, after looking at what I had captured and figuring out what works where, and what composition does what—then I started adding in everything else.

I wanted to photograph the sort of scenes that would allow me to tuck things into little sort of nooks and crannies or in between trees, like in the house and stuff like that, but I didn’t know exactly which would go where. So I was trying to force myself to loosen up a little bit because before that body of work, I was like widely uptight and specific, which is a good thing too—it’s just different.

The West Coast does that to you, right. What do you feel your message through the “Path” series was?

“Path” was an exploration of how we look at our surroundings within the context of sort of contemporary technology. I’d just moved to New York not too long prior to that body of work and I’d been hanging out with a lot of digital artists and this community that was heavily based within the internet. I too, obviously, became interested in this after having many long conversations with these guys. So this is an exploration of how we see our surroundings through the eyes of technology.

When I saw Path for the first time, it made me think about when people are on a trip and they see breathtaking scenery—everyone’s first reaction is to take out their smartphone and try and take a photo of it. And it never looks exactly the same, but remote landscape photos always seem to be so popular on Instagram.

You hit the nail on the head, exactly. For the most part, I’m not the guy that carries around a camera at all times and captures things. I think it’s totally absurd, especially within the context of internet these days. One sort of anecdote that I would tell when I was working with “Path” is the difference between now and for example, even in the ’70s or ’80s—you can go to the Grand Canyon now and it’s going to be breathtaking. But more likely than not, you’ve done a Google search.

You’ve seen hundreds of photos of the Grand Canyon. And I’m not saying it’s going to make you want to go less, but it is going to affect your perception of it once you get there, whether it be that you’ve seen hundreds of HDR photographs of sunsets going down over the Grand Canyon and you find out the sky is not purple there. Not to say that someone would be so silly to think the sky is purple there, but it is this sort of hyper-romanticism that exists now with the landscape.

More often than not, the landscape can be quite chaotic and garish. It’s not always these sweeping vistas and stuff like that. It can be very aggressive and very violent, and that’s something that’s not really a popular perception in landscape right now, but it’s still a very real one.

Do the “Emergence” and “Path” series complement each other?

They are different, but they do feel like a natural continuation of the other one. They’re about understanding surroundings but “Path” was much more about understanding surroundings in context of contemporary technology and consumer technology and sort of aggressive capture, like cameras, and 3D scans and stuff like that.

“Emergence” was made out in the Rockies while I was an artist-in-residence at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory. So I was working with ecologists and biologists while I was out there and helping them with their field research and their analysis—on very, very basic levels, obviously, with those scientists. But that was much more an exploration of science and how science directly quantifies everything in front of us, and how general perception of science is that it’s a 1:1 relationship and it’s absolutely 100% accurate, which is by no means the case. Not to say that science is bad—that’s quite the opposite of what I’m suggesting, but it’s not as perfect as people might perceive it to be. It is very accurate, but it’s not.

Kind of like a photograph, right?

Exactly, which is why photography felt so perfect for this project. The photographs in that series actually acted like my sort of collected data. When working with these scientists, I’d go out and do my “field research,” which was me going out hiking by myself, climbing a mountain, photographing the entire time.

Then I would return back to my cabin, which was my studio at the time, and I’d “analyze my data.” I’d look at the photographs, and understand what the places were, their significance, and I’d create sort of compositions that were based on data analysis coming from them, so a lot of these photographs you’ll see are directly referencing means of analyzing data and data visualization, science, and at some points even creating my own sort of experiments in sort of understanding surroundings.

“Emergent 10” has got this blue gradient, and the photograph that fades into it at the top. Then there’s this square that looks kinda like static. What that actually is, is the exact same photograph that is behind it, but there’s been code that’s been applied to it that rearranges all the pixels in it by hue saturation and brightness. So it’s just a different means of understanding the same subject in the same composition.

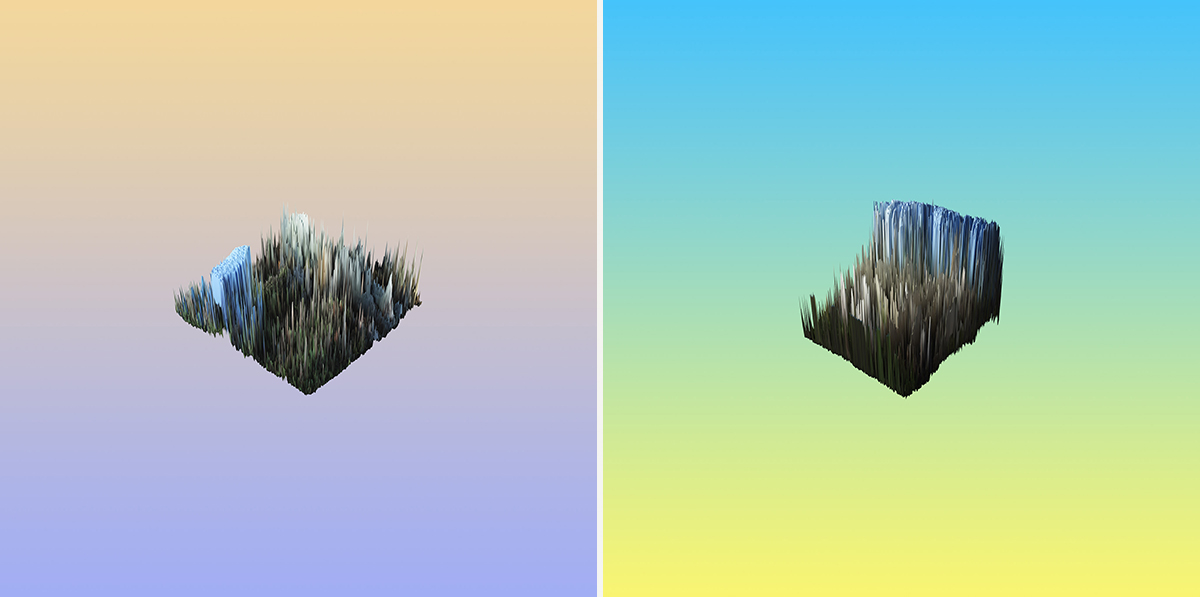

In the mesh translation pieces, those are photographs that have been applied to 3D meshes, just a plane—if you imagine this plane that’s cut up into hundreds of squares in the center of it, and the photograph applied to the top of it, the brightest pixels will make the vertex rise and the darkest pixels will make the vertex fall.

It’s really just creating a sort of map of luminosity that determines height, so it’s this alternative means of photography, in that you can take any photograph you want—whether a picture of your grandma, a landscape, a dog, a cat, a mom—and apply this transformation to it. And you can look only at the way that the light falls in the photograph, so it’s again the same subject matter but translated completely into something more foreign.

Visit Mark Dorf’s website for information on upcoming exhibitions, and recent commissions for DIS magazine as well as a room in the digital gallery Panther Modern (created by anonymous net artist LaTurbo Avedon). For a peek into Dorf’s online sketchbook, visit his Tumblr.

Images courtesy of Mark Dorf