Smriti Keshari + Eric Schlosser’s 59-Minute Immersive Multimedia Experience, “the bomb”

An experimental film that warns of impending doom from the more than 13,000 nuclear warheads globally

the bomb—created by Smriti Keshari and Eric Schlosser—debuted in 2016, on the final night of the Tribeca Film Festival. The audience, standing huddled, watched as electronic band The Acid performed an album-length sonic experiment over a 360-degree visual accompaniment: archival footage and apocalyptic (yet informative) animations about nuclear weapons. Then it toured other festivals—the Berlin Film Festival, Glastonbury—and eventually appeared online for at-home viewers. Now, a reimagined version is on view at Brooklyn’s Pioneer Works.

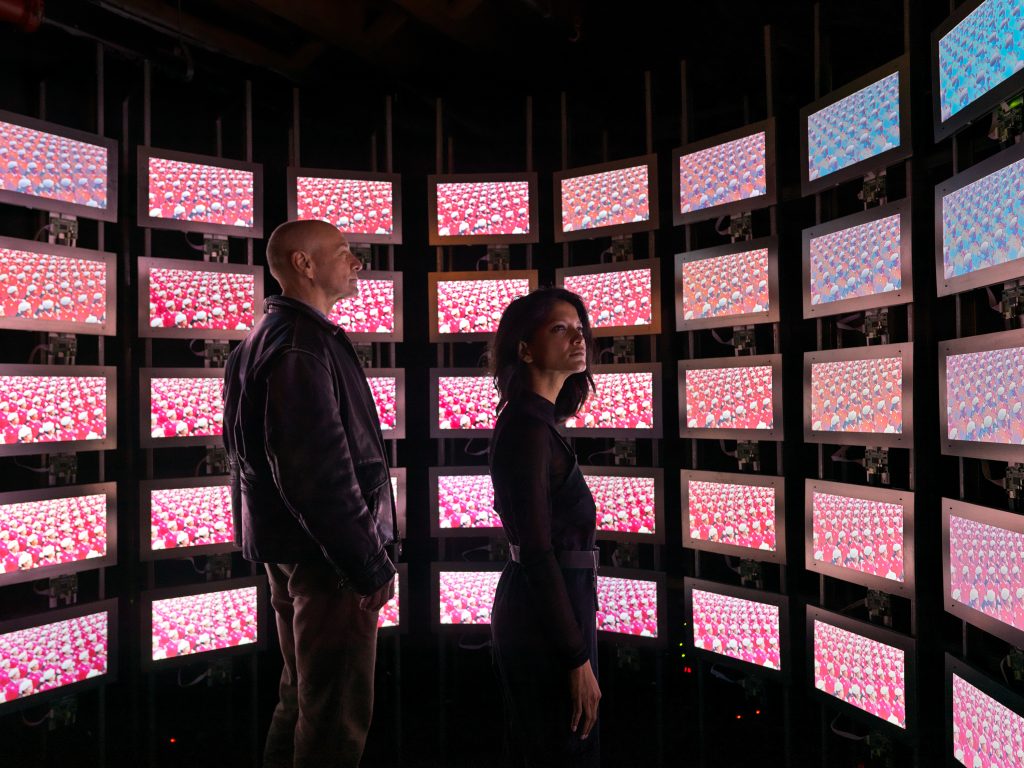

“We feel really proud of the film, which is a linear version. It’s heavily structured, even though that isn’t always obvious,” says Schlosser, the author and investigative journalist whose book Command and Control inspired the work. “We never anticipated anyone would see it that way. We created that film [the bomb] for a multi-screen experience. Then Netflix saw it, and Netflix bought it. It was very helpful to us that Netflix bought it because we were able to use the money to help get it staged, but we never thought of it as a film that would be streamable or something like that. We always thought it would be multi-screen. The museum installation is a variation of the live version that we did, in trying to take these images and divide them up and surround you [the audience] with them.” The installation features a lot of exposed wires and cords, which Schlosser says is “a comment on the technology, which is not only one of the major themes of my book, but also what’s Smriti and I wanted to bring to this kind of installation.”

Director and artist Keshari approached the creative endeavor with the intent of educating viewers on the dangers of nuclear weapons. While they fascinate millions in the same way fireworks or action explosions do, their potential for destruction is far greater. In fact, the duo warned us during our call that an international balance of nuclear power is a perverse death wish with guaranteed doom, and immediate action is necessary to deescalate. In the Pioneer Works installation, the film and soundtrack surround the audience, heightening the sense of urgency. Screens bend around viewers like that of a command center. The chaos—the film playing from different starting points on 45 different screens—evokes the panic of an impending nuclear attack or the surefire destruction that comes as a result of a malfunctioning reactor. The Acid’s crescendoing musical element (available now on vinyl) amplifies the experience.

Viewing the bomb in person truly penetrates, with viewers leaving puzzled as to how we’ve gotten here, and how another catastrophe or (in the case of Hiroshima) terrible crime against humanity hasn’t happened again. Watching the full 59-minute film on loop feels like a forecast of future disasters—as nations around the world enhance their nuclear arsenals.

“Something about nuclear weapons that has always surprised me is that you think that someone who’s wiser is in charge of it, and that it must be the smartest, highest up of the government,” Keshari explains. “But when you really get to understand these ideas, such as Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) or deterrence, it logically—at the beginning—seems to make sense. Then, as you dig deeper, you’re like, ‘How could this be?’ Everything kind of falls apart.”

“These weapons are out of sight, out of mind,” Schlosser adds. “They’re in silos, they’re in submarines underwater, they’re hidden away in bunkers. A big aim of what we’ve done with the bomb is to make them visible, and to not only show them, but show what goes wrong with them.”

Despite the expansion of stockpiles all over, nuclear weaponry relies on old, rapidly outdating technology. In our discussion with Schlosser and Keshari, we loosely reference the lifespan of a laptop whose features will deteriorate even with updates; the core eventually working more slowly and with less power. Work is being done to keep these weapons in check, but are we (the audience or, if war were to break out, the victims) in a position to trust those bearing these responsibilities?

Conversations about nuclear weaponry are also less prevalent and less piercing with younger populations. Not only are those who designed such devices older now, but so too are those that were initially impacted—the generation that underwent nuclear fallout drills in classrooms and considered building bunkers in their backyards. The creators hope that the bomb reinvigorates younger audiences with the same oppositional energy.

Keshari recalls an informal poll she and the bomb artistic director Stanley Donwood did in a bar after a day of production duties. “We just started asking people, ‘How many nuclear weapons do you think there are in the world?’ We’d ask anyone who would walk by,” she tells us. One said 14; another said 190. The actual number is well above 13,000. “No one could believe that,” she says. “And to Eric’s point, they’re completely out of sight now… and culturally, it doesn’t penetrate in the same way. But just last week, the UK announced that it’s going to increase its nuclear warheads to 260—by 40%—and the fact that everyone’s not marching on the streets, it goes to show how much further we have to go in creating work that can touch people, that can really connect with them.”

In its current iteration, the bomb does an excellent job of conveying the seriousness of the subject. Archival footage of accidents, training clips, possible outcomes and beyond is interspersed with animations of an atomic bomb’s structure, its potential failures and the roots of our obsession with such a powerful weapon. the bomb, if nothing else, strives to strip audiences of that affection. “There’s a sort of seduction of them,” Keshari explains. “If you love Jaguars or hardware, this is the most powerful machine ever built… but the bomb is, at moments, quite confronting. Our hope is that it definitely leaves a mark with the audience, no matter how they saw it.”

Timed tickets for the bomb, on now through 23 May, are free through Pioneer Works.

Images of “the bomb” by Smriti Keshari and Eric Schlosser, courtesy of Dan Bradica