Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa

The Vancouver-based artist’s 12th solo show at NYC ‘s David Zwirner gallery melds fiction and documentary through a six-hour film set

by Charlotte Anderson

The recording studio on East 30th Street in Manhattan was once holy ground. Carved out of the abandoned remains of an old Armenian Church, it was a place where musicians shared in a mutual, perhaps now lost, struggle—to record that singular, perfect take. Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, and Billie Holiday all made music there. Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue there in 1959. Pink Floyd created The Wall there in 1979. In its hey-day, the space was generally thought to be the best studio in NYC for its impeccable acoustics, high level of tech and good juju. The studio’s nickname, “The Church,” spoke to both its strange architectural history and its reputation as a place of cloistered work.

Currently on view at New York’s David Zwirner Gallery, Vancouver-based Stan Douglas‘ new video art piece is an ode to this lost artifact. Entitled, “Luanda-Kinshasa,” his film is a rare work of speculative history—a hopeful documentation of a recording that never happened, featuring a band that never existed, situated in a place and time long gone.

The film is an odd synthesis of American, Angolan and Congolese culture that takes place in the year 1974—the year Nixon resigned the presidency following Watergate, the year of Stevie Wonder’s Superstition, the year Muhammad Ali came to Kinshasa for his famed Rumble in the Jungle and the year the Angolan civil war broke out. These subtle associations are what make Douglas’s film somewhat subversive.

Douglas’s piece owes a great deal to Jean-Luc Godard’s situationist-documentary film, “One Plus One” (also known as “Sympathy for the Devil”). The aesthetic similarities—color, setting, and the arrangement of the musicians—are deliberate. In “One Plus One,” a film at least partially about The Rolling Stones, the musicians lurch and sputter forward as they record the song “Sympathy for the Devil.” Godard interrupts his footage of The Stones (taken just after the political events of May 1968) with readings from revolutionary pamphlets and shots of a woman defacing public property. So the recordings just seem, after a while, impotent. In some versions of the film, “Sympathy for the Devil” never comes to fruition.

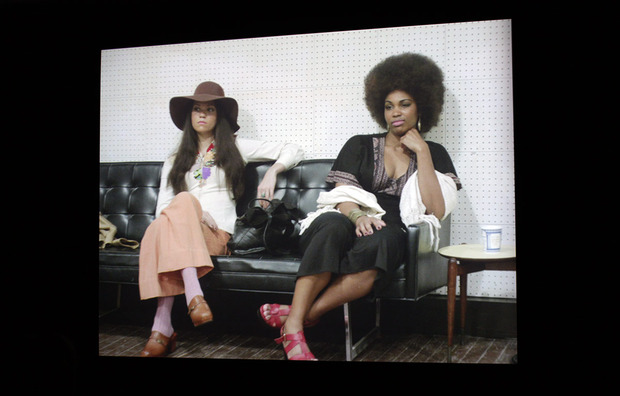

But in Douglas’s work, there is no such dissatisfaction. The band plays on, the sound is virtually seamless. “Luanda-Kinshasa” reads more like an extended jam session. The band improvises over 60 permutations of two distinct ‘songs.’ And in the course of the film, consisting of approximately six hours of footage, the musicians rarely pause. They appear too involved, men in suits line the walls alongside obligatory girlfriends, everyone’s smoking cigarettes that aren’t made anymore. And the band plays. It is in this way that Douglas melds fiction and documentary.

As an artist, Douglas is known for his explorations of history and myth, how these interact and tangle. In his series, “Disco Angola” (currently on view at Victoria Miro Gallery in London until 18 January) he takes on the perspective of a photo-journalist working in the 1970s who splits his time between disco era New York City and Angola. Here, Douglas’s photographs are not simply artworks unto themselves, but are contrived and juxtaposed to one another to create a holistic vision in which the photographer himself is an actor.

Through these invented historical scenarios Douglas offers a solace of sorts—an alternate reality. “Luanda-Kinshasa” is a work of time travel and optimism. Douglas breathes life into a landmark and records an album that was never made, by a band that never existed. And somehow amidst all these falsehoods “The Church” reemerges. A moment in history is synthesized and we’re forced to re-imagine that time and place as something a bit different, and perhaps a bit better.

The video installation constitutes the entirety of Douglas’ solo show at David Zwirner. To enter, visitors walk past reception, through an empty gray room and down a long hall, which opens up into an enormous exhibition space. The overwhelming size of the room begs viewers to take their time with the artwork, which is projected on a single wall. It wouldn’t be difficult to sit in the dark and listen to the entire six-hour-long jam in all of its variations.

“Luanda-Kinshasa” is currently on view until 22 February at David Zwirner Gallery in Manhattan.

All photos by Charlotte Anderson