Stockholm’s Artistically Accessible Photography Destination, Fotografiska

We speak with founder Jan Broman about the brand’s DNA, an NYC expansion and more

Rising from the northern edge of Södermalm Island in Stockholm harbor, an Art Nouveau building bustles with Swedish cognoscenti. It’s early evening and the former customhouse, built at the turn of the 20th century, crackles with the sort of anticipation a marquee exhibit opening promises. The nearby quay overflows with well-dressed locals eager to see the work of Kirsty Mitchell, who is exhibiting for the first time Wonderland—a fantastic, tripped-out ode to grief, escape and relief.

Inside the main gallery of Fotografiska the walls are painted a deep forest green, with real trees and branches spread out over the pillars and ceiling. Rose petals are sprinkled on the stairs. All over, Mitchell’s photographs hang like quiet windows into another dimension, a fairytale of witches and queens, of bright colors and baroque dresses and hair and flowers and ships. “My work is all very linked into the landscape,” Mitchell tells us. Her deep forest connection is evident not only inside the frames, but also in the bucolic vibe of Fotografiska’s transformation. “The woods are my church, that’s where I process; it’s where I connect with my mother.”

When Mitchell’s mother was diagnosed with brain cancer in 2009 and subsequently passed, the trauma subconsciously moved the former fashion designer to pick up the camera. The entire work was unplanned, a seeming force of subconscious will. The elaborate, fanciful photographs unexpectedly resonated with strangers far and wide, quickly gaining worldwide recognition.

Although a momentous evening for the British artist, it is not Wonderland but the institution itself—Fotografiska—that Cool Hunting is here to visit. And it is no coincidence that an artist with the global audience of Mitchell (when launched on Kickstarter, Wonderland skyrocketed to become the highest funded photography campaign in the history of the crowdsourcing site) chose Fotografiska as the home for her first exhibit ever. Whether it’s the great detail the curators commit in creating the precise vibe Mitchell was looking for, or the great care they apply in their signature style of lighting the pieces, Fotografiska has gained worldwide respect in the photography space for its profound connection with the artists who elect to show there.

“Kirsty’s not a photographer, she’s an artist using a camera,” Jan Broman, Fotografiska’s founder, tells us that night amid the din of the packed space. “Her images are perfect for this environment.”

Along with his brother Per, Jan first imagined the idea for Fotografiska when the duo organized a David LaChapelle exhibit in 2006 and nobody in Stockholm knew quite what to do with the idea—including the local media. Harboring a deep love of the art (their father was a printer for Dagens Nyheter, Sweden’s main newspaper), the brothers built a business plan in 2008, found funding and the four-story building, and finally cut the ribbon on 20 May 2010.

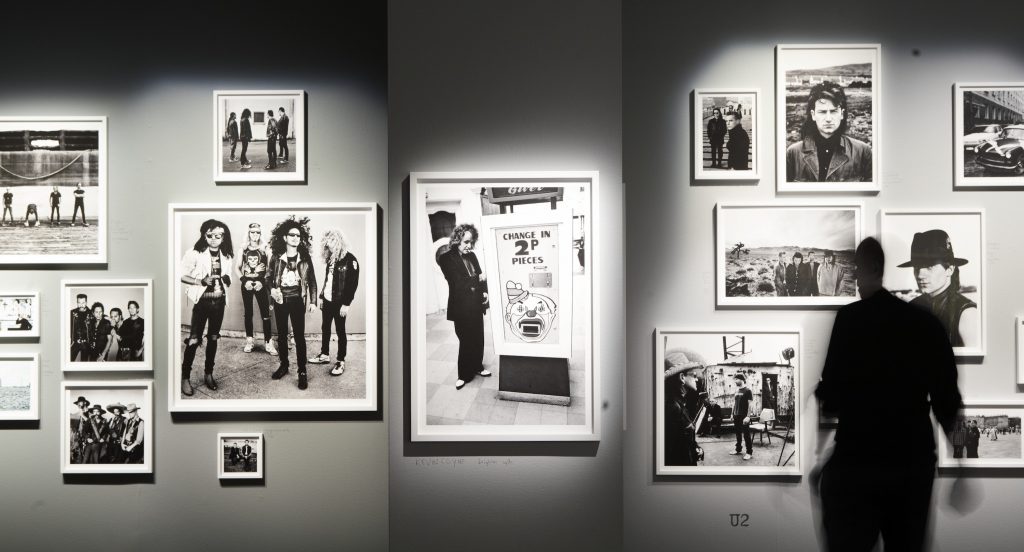

Since then they’ve opened some 185+ exhibits, hosting some of the biggest names in photography—from Annie Leibovitz to Gus Van Sant to Martin Parr. The estates of Herb Ritz, Weegee and Robert Mapplethorpe have deemed Fotografiska worthy of hosting their namesakes’ work. Last year, more than half a million visitors walked through their doors, making Fotografiska the most popular art institution in all of Sweden—even more visited than the venerable Museum of Modern Art across the channel.

Despite its robust popularity, Fotografiska is a bit nebulous in its categorization. Neither a museum nor gallery, it is more accurate to call Fotografiska an experiment in photography—a self-branded “meeting place with the world’s best photography.” It lacks the rigidity and self-importance of a museum while eschewing the overt commercial aspirations of a gallery; anything but your regular museum.

The idea of Fotografiska is not to wonder along its halls silently with earphones on, taking an insular guided tour through works of noted artists. At its core, the brick hall is a dedicated hub of human interaction, creating a space that nurtures thought, discussion, and exchange of ideas.

“Face to face interactions are so important,” Jan says, “Especially in the digital age—perhaps even more so.” To foment this visceral human interaction, the brothers had envisioned from day one a multi-pronged approach to the space. They knew it must be more than just a labyrinth of walls and photographs, so they opened with their mom selling coffee and pastries to customers. The culinary vertical evolved until culminating a couple years ago into an award-winning plant-forward restaurant under the purview of chef Paul Svensson that preaches “Sustainable Pleasure.”

They grow micro-greens in hemp in a cellar below (seven kilos every week), and use a compost machine that transforms all organics—including their menus—into warm soil in 48 hours. They’ve developed a signature beer with Brooklyn Brewery made from their kitchen’s old bread, and then recycle the yeasted mash used to make the beer to bake the next round of bread. Even the ceramics are made of food scraps: the brown butter potatoes, smoked sour cream, fried onion and roe we ate came plated on dishes fired with a glaze made of mussel shells.

But it all must start with pleasure, and in this they excel: the multi-course menu we enjoyed was superb even by lofty Scandinavian standards. There was a puréed potato and beet salad drizzled in truffle oil, and seared octopus with autumn cabbage and aged sourdough. A fine foie gras on toast was actually constituted of haricot, apples and quince. While plant-forward, animal proteins are available as side dishes. Dark and intimate, with cozy wooden tables and landscape views of the harbor outside, the hygge-embracing establishment was voted the Best Museum Restaurant in the World by Leading Culture Destinations. The attached Fotografiska Studio Live bar follows suit, serving excellent cocktails and an ample selection of local craft beer.

Every night both are packed with friends and dates, business dinners and anniversaries buzz with lively conversations. In order to ensure that visitors don’t consider the dining areas divorced from the art, everyone has to pay the entrance fee even if you’re just having a drink at the bar (they also offer membership for about $5 per month, boasting over 15,000 members). This further foments an interaction of art and space; you already paid to get your craft beer, might as well take a stroll through Paul Hansen’s Hand to Hand clean water exhibit.

The building also hosts photography classes, poetry readings, stand-up comedy nights, book readings and even battles of the teachers, a contest that is as much philosophical salon as actual competition.

You cannot be a true meeting place if you’re closing at 6PM

Perhaps Fotografiska’s operating hours are the most salient evidence the Brothers Broman want to create a nexus of ideas as opposed to a silent temple of navel-gazing. It’s probably the most accessible museum in the world: open 364 days a year (only closed during the summer solstice) until 11PM—Thursdays to Saturdays until 1AM. “You cannot be a true meeting place if you’re closing at 6PM,” Jan says. “You need to be open so people can stop by after work to have a drink with colleagues, or meet with friends, or visit on a date.”

Despite its fame in Sweden, the art brand is barely known outside of Scandinavia. All that is about to change, however, as Fotografiska will soon be branching out from this cold archipelago across the pond to New York City. And soon after Tallinn in Estonia, and then London to a glorious Fletcher Priest-designed space in White Chapel. When open the London facility will become the largest photography gallery in the world.

But right now all thoughts are on the move across the Atlantic; it is a major deal not just for the Swedes but also for the city itself: Fotografiska will be the first major cultural museum opening in Manhattan since Marcia Tucker’s New Museum in 1977. The project will take over all 45,000-square-feet of the 19th century building located on the corner of East 22nd and Gramercy Park in the Flatiron District. Three of the six-stories will be dedicated exhibition space, while others will house offices, classrooms, a photography bookstore and of course a plant-forward restaurant. Part of a small church next door will house their speakeasy.

“It will have Fotografiska’s DNA, no question,” vows Jan, “but it is important that we embody New York City as well. That is critical.” When asked to delve deeper into what will make it a New York establishment, Jan keeps some secrets under his hat. But expect a wide variety of artists to show when Fotografiska New York opens next fall, a roster that reflects the cosmopolitan and polychromatic appeal of the city.

Fotografiska will bring a new type of cultural experience to New York

Geoffrey Newman, Fotografiska General Partner and one of the minds spearheading the new outpost, is a bit more revealing. “Fotografiska will bring a new type of cultural experience to New York,” he promises. A long time local and fan of Fotografiska’s Swedish roots, Newman notes the space will encompass exhibition galleries, restaurant, bar, and event venue all under one roof. “It will be a central meeting place for New Yorkers—where people can gather after work for a drink or dinner, catch a talk or live performance, and see some incredible photography in a highly immersive environment.

“We also aren’t beholden to any institutional legacy,” he continues, noting the collective’s small brain trust and nimbleness in action. “Our exhibition schedule allows us to respond quickly to or lead conversations on important societal issues.”

Visiting the Stockholm space it is evident the Fotografiska’s team has developed—through hard work, innovation, and a tireless pursuit of impactful curation—into one of Scandinavia’s most important and powerful artistic magnets. It has clearly grown into a very big fish in a small pond. The only question will be if the team can replicate that magic in the biggest cultural pond there is.