Studio Visit: Aakash Nihalani

A look inside the Brooklyn artist’s studio, where two-dimensional shapes come alive through tape and a unique perspective

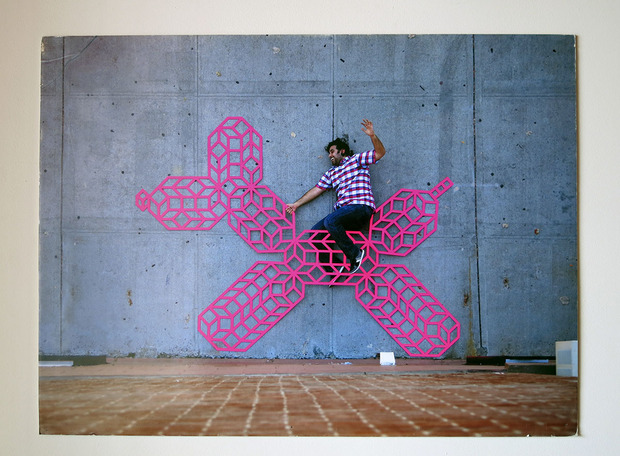

Passing by one of Brooklyn artist Aakash Nihalani‘s fluorescent installations, it’s hard to not take a second look. Then a third, and likely after that, a few photos. Nihalani uses simple materials like tape, plastics, magnets and wood to create geometric shapes that appear to be Photoshopped into the real world. Playing with dimension and manipulating the visual language of space in both gallery and street settings, Nihalani’s playfully captivating work has caught the eye of critics and been featured in numerous exhibitions. Intrigued by his signature style of integrating what are at first blush seemingly digital 3D forms in physical environments, we stopped by his Bushwick studio to learn more about his process and his degree switch from political science to fine art.

How did you get your start in art and design?

I took an indirect approach to it. Growing up, both of my parents were from India, so I guess to them career-wise, I was always sort of pushed toward medicine or law. So when I applied to college, I had all intentions of following up and going to law school. I studied political science and business. Halfway through school I was doing pretty miserably in my classes. At the same time, every day that I came home I was feverishly wanting to work with my hands and I started painting on hats and sneakers and canvas sneakers. A friend of mine in a political class who was in the art program said, “You should transfer to the art program. You’re making all this shit that looks great, and you hate school. Merge the passion and the academics. So I applied and literally my entire portfolio was clothing. They accepted me. Junior and senior year I finished out the Bachelor of Fine Arts degree.

You must have been a bit older than your classmates.

I switched when I was a junior and it was all freshmen because I was starting with ground zero with the art program. So I felt like there was this camaraderie between the freshman—I mean as there always is: you all work together, you start at the same time, it’s all brand new. So I guess in my classes I sort of stuck to myself and kept to my own projects. I definitely wasn’t the social guy in class. And I say that just to emphasize how much I felt like coming at it from the outside helped me in terms of finding my medium and finding my voice and path to follow—because I didn’t know what I could or couldn’t do in art. I didn’t go to an art high school where I had studied painting and art history, figures and things like that.

In art school, I wasn’t bogged down with notions or comparisons. I wasn’t following someone else’s footsteps because I didn’t know anyone’s footsteps. So when I started working with tape it was completely awkward and weird and new. It opened me up to experimenting and feeling free and to not compare. I think comparing and feeling like you have to follow what somebody else did can lead you into results that they got instead of your own.

Once you hit your stride at school, what field were you drawn to?

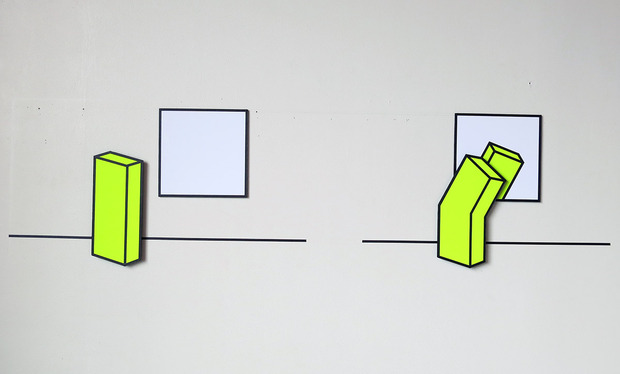

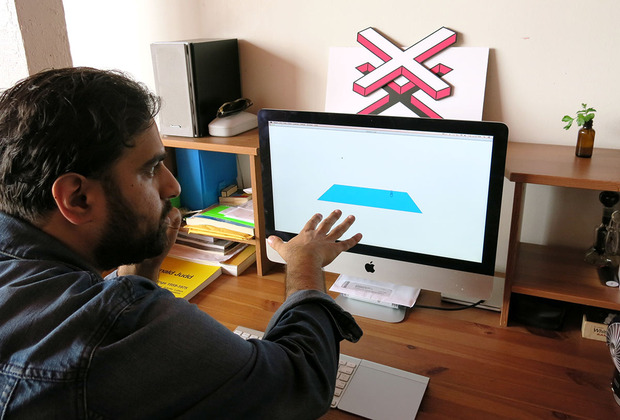

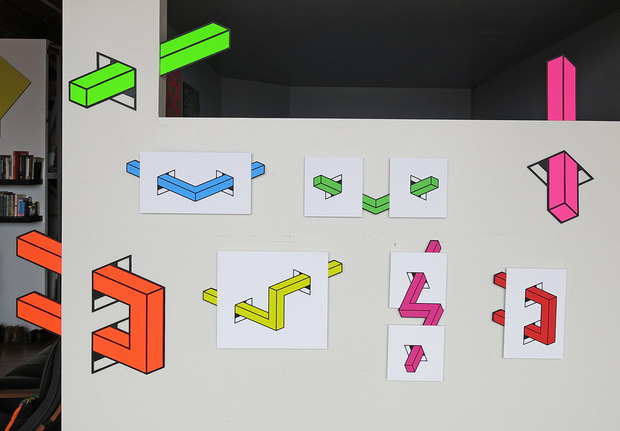

I started specializing in printmaking. I really took a liking to silkscreening with printmaking. Just because it was so quick, I could print maybe like a hundred graphics in just a few minutes and then kind of move on. The way it started, I started printing the graphic of this isometric square cube. I would print hundreds of them, cut them out and basically spend a lot of time arranging different compositions of the cutouts. That’s kind of where I started to develop this idea of spatial limitations. I was working with this really simple representation of space, but it was flat. It was all on paper and from there I started seeing the possibilities.

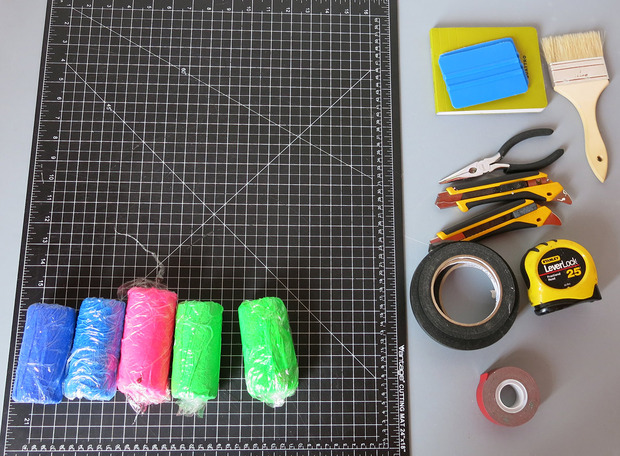

Tape plays a major role in your work.

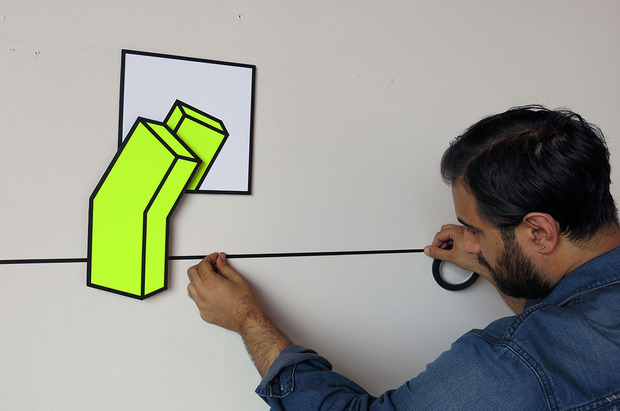

I was hanging a show of all the prints from printmaking in a really rudimentary way, and I had a roll of blue painter’s tape. I was making these rolls, sticking them on the prints and hanging them on the wall like anyone does. There was another artist in this student group show and the pedestal was in the space but the sculpture wasn’t on it, so it was just the pedestal. The shadow it cast on the floor totally matched the isometric rectangles and squares in the prints I was doing. So I took the tape and outlined the shadow on the ground and I think something clicked for me. I left that day and I left the installation on the floor. My teacher texted me saying, “Hey did you do that tape thing on the floor?” And this was a guy who didn’t really take an interest in my work prior. That was motivating to see that someone was responding to it. I can leave something out and all of a sudden someone saw it and it was super-liberating.

The tape became a great way of bridging that gap between creation and exhibition.

One of the things about being in art school, especially when you first get in, is that it’s super lonely in a way. Especially for me, because I was in the studio making things and you don’t have exhibitions all the time so you make them and store the shit and it’s this repeat process and there was this deadness about it. There was this lack of life to the process and to the creation. The tape became a great way of bridging that gap between creation and exhibition. After that first tape installation in the gallery I was addicted. I plastered the NYU buildings, the janitors were pissed off at me, but it was easy to take down.

Then you really took it to the streets.

I was always really excited about outdoor work, but I was never really comfortable with the mediums of it. With spray paint, you have to pick a fake name, work at night, always be on the lookout, never take responsibility for your work and run from cops. All of these things that seemed counterintuitive to me. But working with tape was perfect. I could use my name, work in the daylight, if the cops stopped me I could say, “Look, it’s just tape,” and I can take it down and walk away. There’s this removal of the aggression, which freed me up a lot.

How has your work evolved since you first started taping outdoors?

With anything it’s this kind of R&D process of finding something you like or a direction you like, then exploring it. Something happens in the midst of making those new works, then you can follow a tangent in a new direction. From the beginning, a lot of the work had the mentality of a graffiti artist, in that I was tagging the shape of a geometric square everywhere. It wasn’t necessarily that it was in a place that always made sense, I was just getting the graphic out there. Then I think over time, the work started to become a lot more site-specific, a lot more reactionary. It started to have this narrative quality to it, a sort of humor added. I always saw the graphics as becoming personified. You can look at this narrative and attribute your own feelings to the scene.

The mediums have also changed. I’ve had the opportunity to work with laser-cut aluminum and c-and-c-ing wood. I started working with magnets recently which has led me in a new direction. The tape has stuck as this control medium. That’s been the through-line. With tape I started getting exhibitions and gallery shows and one thing about tape is there’s this difficulty in the permanence, it’s not archival. From there it’s been how to best create the work I want to make and in what mediums.

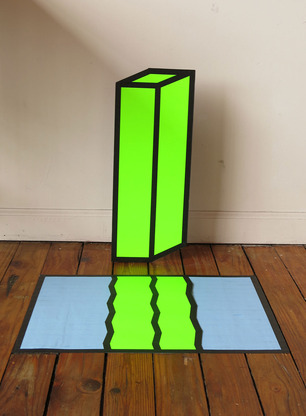

A lot of the outdoor work I did was quite site-specific. So there was this environment that caught my eye and I had an idea. So I would react to that. Whereas in the gallery space there isn’t so much of this visual, wrap-able landscape to playoff, it’s just white. A lot of the work I’m making now tends toward still utilizing that space, and creating works that are reactionary to that. Even though it’s a bit bland, the gallery, you still have a floor, ceilings and flat walls. There are things about the space that are ubiquitous and standard, that you can speak to.

That’s one of the great things about the tape work…It’s made for the act of making and for the act of sharing.

Is that more difficult than working with a dynamic landscape?

It’s not necessarily more difficult, it’s just a different process. One of the great things about working outdoors is this feeling that the work is being created not just by you but by your surroundings. In the gallery you have a set of paints, a canvas and a paintbrush. Whereas outside you have a fruit vendor, you have a dog and a dilapidating brick pattern. All these things that don’t come from an art store, but become the components that are creating the work. So in that sense, there’s a large difference. I don’t know that one’s more difficult, but I find the outdoor work to be a lot more fun. Maybe that’s because I’m able to let it go and throw it away and not attach a price or a value to it. That’s one of the great things about the tape work in general, is that there isn’t this sense of having to store it. It’s made for the act of making and for the act of sharing. From there it’s sort of left to nature.

How do you achieve the digital, almost photoshopped look of the work?

A lot of it is sort of inherent. It’s almost always straight lines. Combining that with the palette that I’m using which is fluorescent, none of it exists in nature, I think those two automatically have a sort of minimal digital aesthetic. Also beyond those inherent qualities, when I’m making the work there’s this point of perspective, a vantage point. Where the work attains this volume to it, a three-dimensional quality to it even though it’s flat. That graphic within the space of reality, gives such a contrast in the visual language. It automatically looks digital, like I placed it in there with a computer.

I’ve shied away from laser cutting and working with vendors. There are these nuances that you have control over and you have your hand in it. I was missing it over a few years that focused more on production quality object works. I’m taking a step toward having control over the whole length of the process, from idea to production. When I originally started one of the easier ways to create objects for a gallery space was to cut out shapes. So the more I’ve been growing, the more I’ve been aiming to achieve something greater than something decorative. Instead moving toward making site-specificity and that reactionary attitude of making art into the gallery space.

Check out more of Nihalani’s work on his Tumblr and keep an eye on his site for future exhibitions.

Photos by Hans Aschim