Studio Visit: Balint Zsako

The Brooklyn artist’s vocabulary of universal symbols speaks to common human encounters

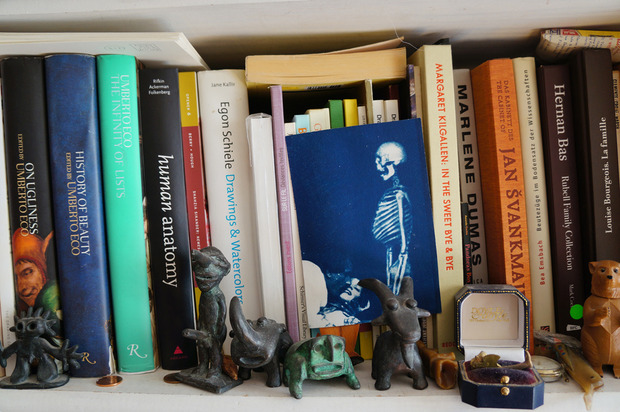

Balint Zsako, whose work first caught our eye in 2007, disrupts the language of Old Master painting, with a vocabulary of modern symbolism and technique. In his view, “Everything changes, it’s important to have things of your own time.” Several lamps surround the Brooklyn-based artist’s work surface, the most prominent light enters through a street-facing window. The studio is otherwise lined in shelves, stocked with books on art, anatomy and influential curios. His father’s sculpture, Indian miniatures, and cyanotype developed on Zsako’s Williamsburg stoop, form tableaux. The allocation of space, to a compact drafting area and abundant references, is echoed in Zsako’s oeuvre; collage and paintings that engage viewers in dense narratives realized at an intimate scale.

The majority of Zsako’s collages exist as bodies of work commissioned by patrons, who furnish the artist with a basis of classical prints and engravings to reinterpret. One collector, fascinated by mortality, proffered the anatomical drawings of Albinus, Vesalius and later, a damaged and incomplete set of Audubon Birds. Zsako, eschewed clipping the originals, purchasing instead 15 copies of Audubon’s Birds of America for use in reimagining all 435 plates.

While thought of as the father of the conservation movement, Audubon was also notably a compulsive huntsman and gourmand whose subjects were posed in “lifelike” positions through the use of wire and thread. Under Zsako’s knife, sequestered in a ground of Old Master paintings sourced from auction catalogs, each bird enters the human world, realizing “a wholly more complicated narrative.” “This kind of painting has a history,” says the artist who knowingly distorts its conventions, “and most people are familiar with it.” The Double-crested Cormorant perches on one of two nearly indistinguishable images. In the second the bird departs, creating a sequence that takes on a filmic quality. There is a similar layered meaning in a violent scene erupting into a banquet while beneath the table a still life of a deceased goose mills between the diner-victim’s legs. The Black-Throated Bunting (or Dickcissel) observes from a planter in the foreground. “There’s the frission of ‘Why, how does this go on? How does it end?'” says the artist who models viewers’ thought processes, but insists there are no objective meanings. The imagery doesn’t go much past early Impressionism, when the artistic voice became so pronounced, it no longer blends with the style of the birds.

Zsako is a student of the paradox of collage imagery, “When it’s disjoint it’s still seamless.” The work can become so complex that Zsako’s wife, photo editor Natalie Matutschovsky, will run her finger across the images to understand the cut. Having completed collages for the first 400 plates, ways of seeing and technique have expanded. Zsako has returned to improve on a selection of earlier works. The artist borrows, not only from the narrative approach of Victorians and Surrealists but the fragmentation and geometric abstraction notably explored by James Rosenquist, John Baldessari, and John Stezaker. All are visible in an image in which Wilson’s Storm-Petrel dives past ships towards the image of a woman reclining. In gamboling through the history of collage, Zsako learned the power of “a certain element and edit, a cut.”

The artist’s hand-rendered pieces are also conceived with an eye on the Old Masters. Zsako prepares a series of canvases, capturing classical figural poses, painting colorful bodies without their hands or feet, in order to retain narrative freedom. When ready to iterate a work, a process viewed akin to writing a short story, he draws from these prepared canvases and sketchbooks of brief notations where he’s recorded resolutions for working gestures. The narrative unfolds over a day or two in a “focused” and “controlled” process. As much time is spent on looking as is on rendering.

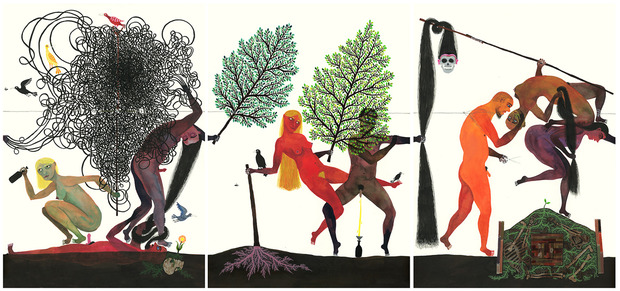

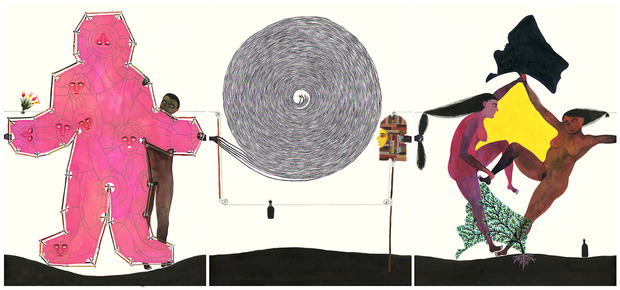

Zsako was attracted to the idea of “a narrative extending over a larger landscape” but discovered that many days pouring over a canvas led to the fear of losing the work to a spill—the hazards of watercolor and ink—so, he’d retreat to familiar gestures, hindering an otherwise fluid storytelling arc. The medium forced conservatism on an artist impelled to take risks. Zsako realizes his characteristic flow, while deepening audience engagement, with his series Modern Dance. In it, every painting is connected at the ground by a hand and a string. Recurring elements such as bottles, birds and skulls add continuity. Connections are forged in inked tangles of hair, words and “machine drawings”—industrial motifs the young artist began exploring at 10 years old. It is a vocabulary of symbols, for a painter who gathers an awareness of how imagery is read, though he commits to no narrow scope. Figures are rooted to the ground and reaching skyward, rendered in every state between ecstatic and abased, with all the bodily realism of the human condition. For many, it’s an invocation of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthy Delights.

With Modern Dance the artist has invited his audience to partner actively in the creation of narrative. The works are tightly framed and, at first like the collages, appeared “too seamless.” People had to be “encouraged to handle the work, told they could be rearranged.” Each is a story fragment from which collectors hew meaning by assembling their own linked, personally relevant narratives. The work is sold, several panels at a time.

“I want the work to be generous,” shares Zsako, who eschews a specific reading, insisting that as an artist, each piece captures something ephemeral. “In a way it’s just a feeling,” he shares. “I don’t verbalize what a story means, or articulate the narrative the ways a viewer might. People bring what happens in their lives.” Zsako shares a profound appreciation for his audience’s interpretations. “If you encounter something that fits your life at that moment, than there is something special.” The aim here is to render what is at once universal and subject to interpretation, but in a timely language. Zsako creates with the intention of partnering with his audience. “You,” he suggests, “fill in the second part of the work.”

Images courtesy of Balint Zasko, portrait by Natalie Matutschovsky