“The Art of Play: A Retrospective of William Accorsi” in The Catskills Urban Cowboy Lodge

Whimsical works and inclusive erotica from the folk artist at an exhibition during Upstate Art Weekend

A few weeks before the Upstate Art Weekend opening of William Accorsi‘s retrospective at Urban Cowboy‘s Lodge in the Catskills, the imaginative 90-year-old folk artist died. Leading up to the powerful, playful exhibition, Accorsi spent time developing new pieces and plotting his future. Accorsi knew that death wasn’t far, and yet his empowered vision was to continue crafting sculptures, complete an autobiography and reconnect with some of the institutions that exhibited him earlier in life.

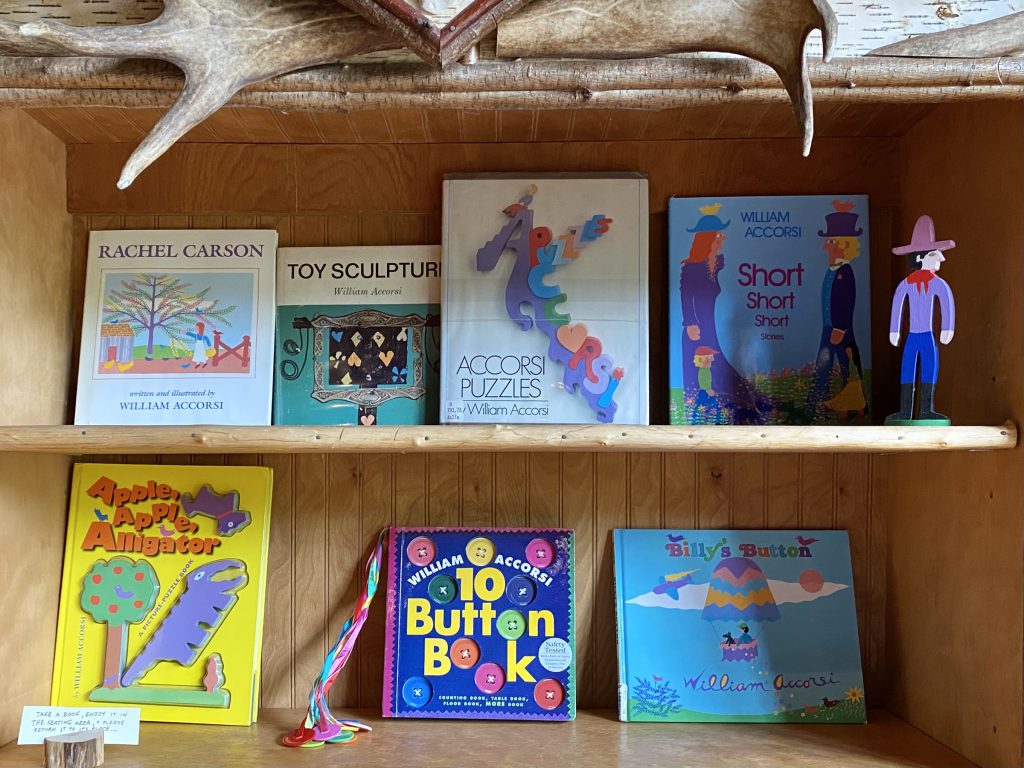

Though Accorsi isn’t a household name (except for those who may have read his beloved 10 Button Book as children or to children), his resume is a mighty one. He produced hundreds of wooden sculptures in NYC over the course of decades. These colorful, childlike works were shown at the Smithsonian and NYC’s Museum of Arts and Design, among many other places, and the artist and art teacher began to make a name for himself. Then, he seemed to step out of the currents of the city scene and settle into reclusive creation. All the while, he continued to produce a wondrous artistic collection which varied from toylike mobiles to erotic pieces that present all types of sexuality.

About six months before the retrospective, curator Kayleigh A Myer met Accorsi for the first time. Myer lives in the region and recently (with her boyfriend) refurbished a liquor store in the town of Hunter, introducing everything from natural wines to Japanese whiskies to its shelves. Myer was the person to propose the Accorsi show to Urban Cowboy, but the reason is steeped in chance and charm.

“I was hired to photograph his collection,” Myer tells us, as we walk through Accorsi’s colorful, balanced and compelling works together, “by William’s friends Barbara Isenberg and Paula Silver, who were like his family, and helping him during his last few months.” Though her background aligned more with fine art photography and recent gigs had brought her to food photography, the Bard alum took the job. “He had tons and tons of pieces that he was storing in his apartment toward the end of his life.” Immediately, she was enamored with the art and the artist.

“He wanted people to surrender to their feelings of intuition about his work,” she says. And as she did so, they became friends. Myer and her boyfriend would visit Accorsi several times a week to learn more about his life and his collection and observe him working on new pieces. “Sometimes,” she said, “he would be so discreet about creation—he would hide his scroll saw in his bathroom so that when caretakers came in, he wouldn’t disturb anyone. He would sit in his bathroom and make pieces.”

Erstwhile, Myer began spending more time at Urban Cowboy’s Lodge. Her boyfriend was a beverage consultant there—and as the rustic and stylish hospitality venture tried to navigate opening (and staying open) in a pandemic, Myer herself also joined the team, taking on everything from bartending to making floral arrangements.

As her relationship strengthened with Accorsi, so too did her relationships with his friends Isenberg and Silver. In fact, Myer invited them to stay at the Lodge and toured them through the gallery that Urban Cowboy creative director and fine artist Nate Fish had built. It was then that they realized this would be the perfect location for a retrospective. Fish and the Urban Cowboy crew fell in love with Accorsi’s work and were determined to host a show, only in a second location on the grounds, with a stunning view of the Catskill Mountains in the distance. Though Accorsi never visited the site, he was aware of and excited by the unfolding plans.

“I wanted you to feel like you were walking into a playful toy store for adults,” Myer explains. “It was less of me methodically placing things and more like playing with the artworks themselves, building a scene, telling a story. I wanted it to feel like him. I did not want there to be a division of pieces—or a separation of the erotic—because that wasn’t him. When you walked into his apartment, it was filled to the brim with all of these works together.”

The plane strung in the show’s center has been exhibited in numerous exhibitions already, dating back decades, but much of the work on site is recent. Some of the pieces, however, are reproductions by Accorsi of classic concepts he introduced decades ago. Roughly the half the works in the show came from Accorsi’s nearby apartment, and half originated from Accorsi’s Provincetown gallery, Woodman Skimko.

“He was making items for the show up until the week before he passed,” Myer says. “It was fascinating to watch because of the dexterity necessary to make pieces like these. He was so drawn to creating. He couldn’t stop. It was an impulse for him.” Isenberg and Silver asked Myer to act as curator, and she began to read his years of press and excerpts from his journals and manuscripts. She also remembered her own experience reading the 10 Button Book as a child.

Regarding installation, Myer says, “I tried to lean into William’s tendency to build these seemingly precarious desks and shelves around his home and studio that were somehow actually very practical and just worked perfectly. In this show, I really tried to channel his personality and process as much as possible, as opposed to utilizing the typical white columns/fixtures found in many gallery spaces. I wanted to build a portrait of a life in this space. To the best of my ability.”

From Accorsi’s hat and scarf hanging near a replica of his work station (which Myer packed up herself), to the sheer number of pieces that are featured, visitors do get a sense of the artist—of the many personal dimensions constructed by his exploration of disparate themes through a signature style.

Accorsi’s erotica is truly joyful. It’s silly and spontaneous, mature and magical. The exhibition succeeds in reminding all who see it (or learn about it) that an abundance of Accorsi’s art exists and must be preserved and presented.

“He wanted to live forever,” Myer tells us. “When I met him, he had terminal cancer and was already 89 years old. There was the feeling that he would pass, but we did not expect it to be so soon. That was the hardest part. There was hope that he had a year or two left, and in that time he was going to do so much.” Now, of course, his work allows him to live on and it shares one clear message: joy must be expressed at all ages.

Images courtesy of Kayleigh A Myer