The 2013 Aperture Benefit with Jakob Trollbäck

A preview of the installation at this year’s event and an interview with its mastermind

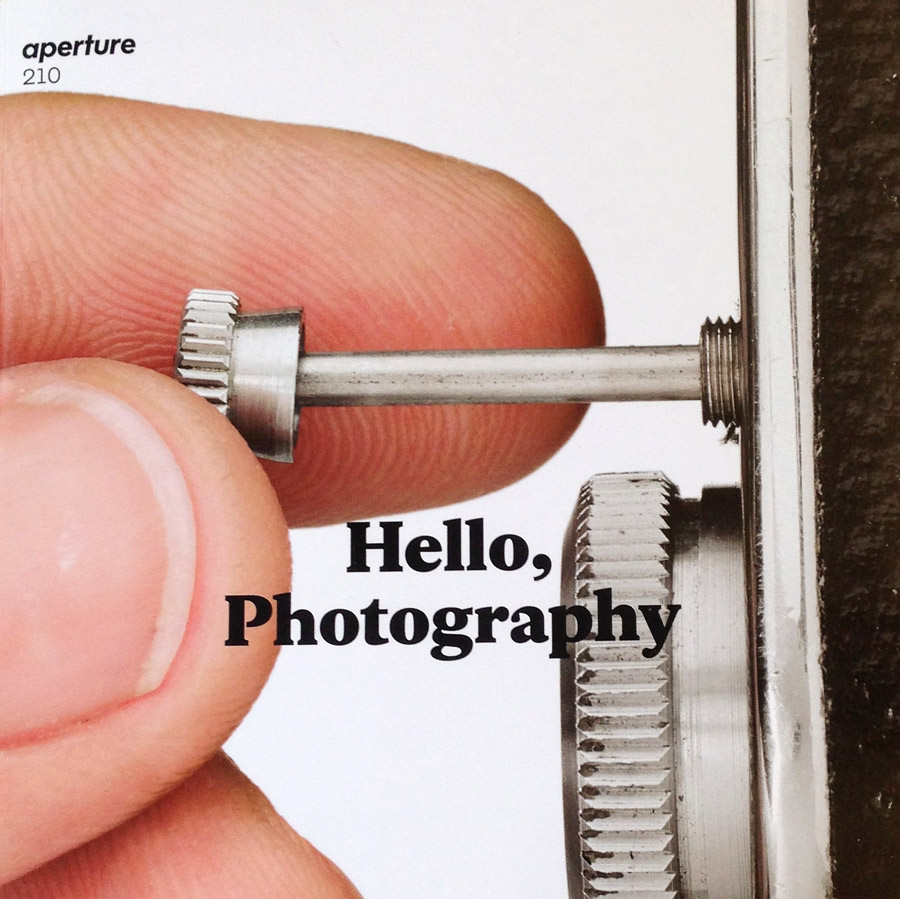

For this year’s benefit, Aperture is hosting the work of Swedish designer Jakob Trollbäck on 28 October at the Frank Gehry designed IAC‘s New York City headquarters. For the first time, the not-for-profit photography foundation will throw its annual benefit party featuring unique performances and 1/1 commissioned works in support of the Aperture Foundation’s education and visual-literacy programming. Trollbäck, the graphic-savvy designer of NYC-based Trollbäck + Co., has created an exclusive feature for the event that’s been specially designed for the IAC’s video wall that spans almost an entire city block. The visual program explores a series of slow moving, microscopic vignettes that examine a world of photography never before seen at this scale.

We got an early peek at Trollbäck’s stunning graphic feature and have stills to share to preview the photo-filled event—and we can only imagine what the experience will be like on a wall as massive as the IAC’s. Trollbäck kindly met with us before the big night to discuss his work for the 2013 Aperture Benefit and Auction, as well as his path as a self-taught designer and lover of all things creative.

What was being self-taught like for you?

This time, I want to take a different angle on this. I think you can split self-taught people into two groups. There’s the kind of loonies who are just crazy and get obsessed by one thing—that’s a thing, right? Well I think for my category, I took for granted when I was younger that I could do anything. I felt that when it came to school, that most of it was just dumb, so undynamic mostly. It can get dull. After high school I was just like, “I don’t want to do this anymore.” I was a DJ and really into music, and I was into electronics, building synthesizers and stuff like that. Then I met a guy who had a gallery, and he had parties on Saturdays and he asked me if I would DJ there. It went really well, and then he took over a movie theater in Stockholm. And at this time we were making flyers for events with what we had, you know typewriters, rub on letters—and then I came across a computer. And well, I was like, “Whoa.”

I think what you need to have is some sort of drive just to say, “I want to do this.” Since I was self-taught, no one wanted to hire me in Sweden. Back then there was just a path. It wasn’t like America, where everyone I met was like, “Screw that! If you’re talented, there is always a job for you.” No one would say that in Sweden. A lot has changed in 20 years, of course. So I just moved here and it was kind of by chance that I ended up doing things in motion.

What is so fascinating to you about what you do—music and motion?

OK, this will be a long answer. I think ultimately, the driving force behind humanity, besides these reptilian instincts for food, shelter and reproduction, besides all that, I think what the frontal lobe has given us this self awareness, and with that we are always figuring out ways to better our lives—always finding new solutions to things. So I think that it is sad that people, when they talk about creativity, often just talk about the arts. Because when you get a new job or start a new school, you’re going to spend the first few weeks figuring out a routine—it’s all about figuring stuff out and learning what you can do better. So that whole thing is just driving us, and I guess for that I’d be very happy being creative in any medium. I wouldn’t be good at all of them, but at the same time it’s like [Malcolm] Gladwell, if you do anything for long enough, it’s going to get better, if it’s not something you totally suck at. What was the question again?

What’s so fascinating about what you do every day?

So creativity is all about transformations. And ultimately if you can distill them, it’s about the moments when transformations happen. Some of the things that can be very linear; you can be friends with someone and then suddenly you realize you’re in love. If you really think about it, that’s when it happens—that’s when you look at him or her and know. To find moments, that’s fascinating. And the difference with other mediums I’m fascinated by—like photography is huge for me—when we put a time axis on them we can tell mini stories and create a mood. You’re looking at this, and suddenly it’s something else. It’s no coincidence that the first special effects were performed by magicians. You’ve seen those guys; they have a little ball they’re holding and then, woosh!—it’s four balls. That is so lovely, you just want to live in that moment of “Aah!” It’s just because our brains get so excited that things can be different. Why not do it differently?

So how does photography factor into what you do?

OK, I’m going to name-drop. I once worked with Richard Avedon, and the amazing thing when we were at a shoot involving just a woman jumping was with every shot—he got her at the top of the jump. And if you look at his photos you wonder how it happened. It was just that moment, and he was just amazing at seeing a moment before it even happened, with reaction time and all. It’s about finding those moments—I like that idea—capturing the mood, the light. My biggest revelation when I started with photography was that light is volumetric. It’s easy to see it as something flat through the view finder, but it’s really a volume.

I had a creative partner who was an amazing photographer, and it annoyed me because I was a shitty photographer. The best driving force was to show people that I was good. I know that’s not the best way, but sometimes that’s all you have. I know I’m a perfectionist—I want the satisfaction of doing something perfect, but I could never be driven by just some zen-like, “Oh I’m going to work on this for 45 years until it’s perfect.” What I did was I started a Flickr account and published a photo every day. I didn’t really share it—just with two or three people—and I felt like I couldn’t disappoint them by putting up something that wasn’t good, so I worked really hard on it and, after a while, you start to learn what works and what doesn’t. I took 20 to 100 photos a day, just on my way to work and stuff. It’s amazing what you can learn. I think for a lot of people, the biggest problem I see is that they fall in love with what they are doing, and I’m the opposite of that. I actually don’t like what I’m doing. I’m critical of it and that’s a big driving force to be better.

What’s the difference between doing creative work, like for Aperture, and doing work for clients?

It’s very different. I think were at a level where clients expect us to give them our stuff, but of course bigger clients with bigger budgets get anxious and start to second guess everything. That’s why I’ve always loved work we’ve done for conferences, pro bono, because those jobs are free and the people just want something really cool. What are they going to do? They are just going to eat it. When I was a new designer, my brother asked me to do a brochure for him and it probably wasn’t very good because it was early on, but then he asked me to change this and that, and I was like, “Dude, that’s not part of the favor process.” Ultimately you do some of your best work like this.

For Aperture I was thinking of how to transform something and look at it another way—something in the universe of photography that wasn’t an actual photograph. We are doing eyes because they are very central, and part of their little symbol, part eye and part lens. We also found a slow motion lightbulb, and were like, “That’s awesome, no one has seen that.” Then the lens. You see how deep they can be in camera beauty shots, so why not explore the aesthetics of its glass and craft. It’s all observations, or meditations of different things. Meditations.

Are you still learning from what you do every day?

Yeah, I am. But within this field, I already know how. It’s not so many revelations now. Imagine you like to play music, and then you play something, you’re like, “Oh my god, I wrote a song.” Then you put together a band, and you’re like, “We’re a fucking band, this is really great.” And then after a while, all you’re doing is new albums and you want to do something new with it—look at life, looking at different things. Like Joni Mitchell when she did Blue—she pulled off her skin and was so naked and sang about how things suck. So anyway I feel like what I’m trying to do more. I feel like I’m having more revelations in understanding how I work. Ultimately I’m so much better at understanding people, and that’s a strength for us when it comes to branding. I meet people and get feedback and understand things—what’s going to excite them. And that’s something that you can really use when you’re in any creative business. The difference is that we’re still not doing art. You can look at that thing, like it could be an art installation, but at the same time it really has a message. If you’re an artist, you tell people, “This is how I feel right now, look at my canvas. I don’t care what you feel as long as it’s something, whatever.” This is so much more about understanding people, opening doors. Now we’re going to have something exciting to tell you.

This is more purposeful?

That’s the fundamental difference between art and design.

Tickets are available online for the special event, starting at $250.

Lead photo by Lauren Espeseth, video stills courtesy of Jakob Trollback