Design Indaba 2019: Dong-Ping Wong of FOOD

From vertical parks in Chinatown to Kanye West projects, the NYC-based studio is all about ideas

Questioning if the design process can be faster or more meaningful, during his speech at Design Indaba, Dong-Ping Wong of FOOD offered a glimpse into advanced and sophisticated ways of thinking about architecture. Based in NYC, FOOD has a unique way of approaching architecture, through a creative approach that appears almost as a performance. Very often, they spontaneously develop their own ideas, through a process that Dong-Ping Wong demonstrated during the Cape Town event.

After presenting some of the firm’s concepts and projects (such as Chinatown’s Golden Tower, Off-White stores, a stage for Kanye West, the Hudson River’s + Pool and a radio station), Wong called Virgil Abloh, who was in Paris preparing for his Off-White fashion show. The two brainstormed in front of the audience and designed a “15 Minute City”—their ideal town. It took shape under our eyes as Dong was drawing it with skyscrapers, parks and more. The drawing, dubbed Nature City, was then turned into a poster, printed in a limited edition of 250 copies and distributed for free to the Design Indaba crowd.

Such a quick process is far from what we expect from traditional architecture and we met face-to-face with Dong to understand it a little better.

Is there a method that you apply to your creative process?

I’ve noticed a pattern, and it actually started happening when we started sketching—like I did on stage. I started sketching as part of what we do in the office, maybe only three years ago. We spend a day or two of learning about the project—the site, understanding the size, the scale—really baseline stuff. Then we go straight into ideas. What we’ll do lately is involving whoever’s on the team or whoever in the office is free at that time, literally around the table, trying to come up with ideas as quickly as possible. It’s really, really intuitive. You don’t think about it very much. They’re not necessarily great ideas, but there’s always a spark in some of them and then we’ll take much more time to develop those, of course.

Half the time that you’re researching or trying different options, you’re just delaying your own intuition

I think it was a reaction to a lot of my training at OMA, where the model is you research, research, research, iterate, iterate, iterate and you have a thousand options down the road as you go. I realized that half the time that you’re researching or trying different options, you’re just delaying your own intuition. You’re just delaying a decision basically.

In the worst cases, sometimes you get to a point where you don’t even remember anymore what you thought was important—you have too many inputs, too much information. At FOOD, we want to put something visceral on the table. I think that’s really important for us because whatever that visceral thing is—maybe represented through a sketch or model—I feel is the thing that communicates the best and resonates the best with the people that are going to use the building. It’s that immediate experience you get when you use it.

The + Pool project was just that you want to cool off in the river. It’s as simple as that. You’re sweaty, you want to jump in and you want to feel the cool water. And that’s what’s driven everything, every decision was driven by that initial reaction. Then we end up developing in very different ways once we figure it out. But I’ve noticed that fast sketch has been really important for us.

An impressive element of your work is how you approach different fields and use different talents at the same time.

There’s a proliferation of people that do a lot of different things, especially in the creative world. Part of me thinks that when we end up doing something that is not strictly architectural, it’s actually not for a desire to do that thing. The desire to do architecture is not purely because I want to build a building, it’s because I want to build a building to create a space for a community of some sort. So there’s always an interest of bringing people together or having an effect on the city.

Today, designers often work in global and fluid groups—extreme versions of the Warholian factory or the Renaissance workshop. I’m thinking about the interconnections that you must rely on—many seem to revolve around figures such as Virgil Abloh and Kanye West.

Kanye is definitely a central connector. He’s incredible and I legitimately think he’s an artistic genius. But what’s amazing also is that he is so incredibly good at finding people and bringing people together. Now, obviously, he’s in a position he can call anybody and say, “Just be here tomorrow” and they will show up, but he had to get to that position. For one: he knows who to call. But it’s more exciting that he’s always interested in finding new talent. And I think it’s not so much about giving kids a chance, that’s not really his core interest. Rather, he wants to know if that kid is actually doing things better than the established person.

Both in Kanye and Virgil’s studios, there’s always a ton of people working on every aspect of things. There is something Renaissance when you go to their studios. There’s five tables or one big table and different things going on at once. There are people doing clothing, there’s a radio thing happening here, there’s architecture stuff happening there, there’s a book being designed.

It’s never one thing at a time—from ideas to research and beyond. Maybe some things will happen immediately, maybe they’ll be great, maybe they’ll stay there for years, maybe they’ll be trashed.

This is also an issue I have: being smart or having an impact in real life? I feel like the only way to test if something’s going to work in real life is to make it. Test it try it, look at it, feel it, see if anybody cares about it. And then do it again and again and again. Virgil is a great example. He is so prolific because he just makes it, makes it, makes it. And he’ll probably be the first to tell you it’s all in one long project, one long prototyping. Everything is a test, everything is the next thing, let’s try that.

That’s similar to traditional scientific research. One key moment for the success of a research is peer review—you might think you have achieved a great result, but that’s not up to you to say. You need another scientist to validate or refuse your achievements. Do you feel like that’s similar to what you’re doing—since you are constantly reviewed by your peers and the public?

I think we do that all the time. I think it’s a way to get an idea out there, but it’s also a way to see if an idea is going to stick, or if there’s interest in that idea even. For + Pool, we did not expect that much press and it didn’t mean that a lot of people were interested. But it had some sort of resonance with a wider audience and that was huge validation. So instead of one big peer review, at the end, it’s all these little ones that hopefully build up.

I’m curious if success also makes it harder to do that kind of constant production and constant public display of things. I feel like I’ve seen people getting incredibly successful and then have a huge concern over peer review. It’s like they can’t put anything out unless it’s the greatest thing in the world. Which you can’t always do.

What do you foresee for the future of FOOD?

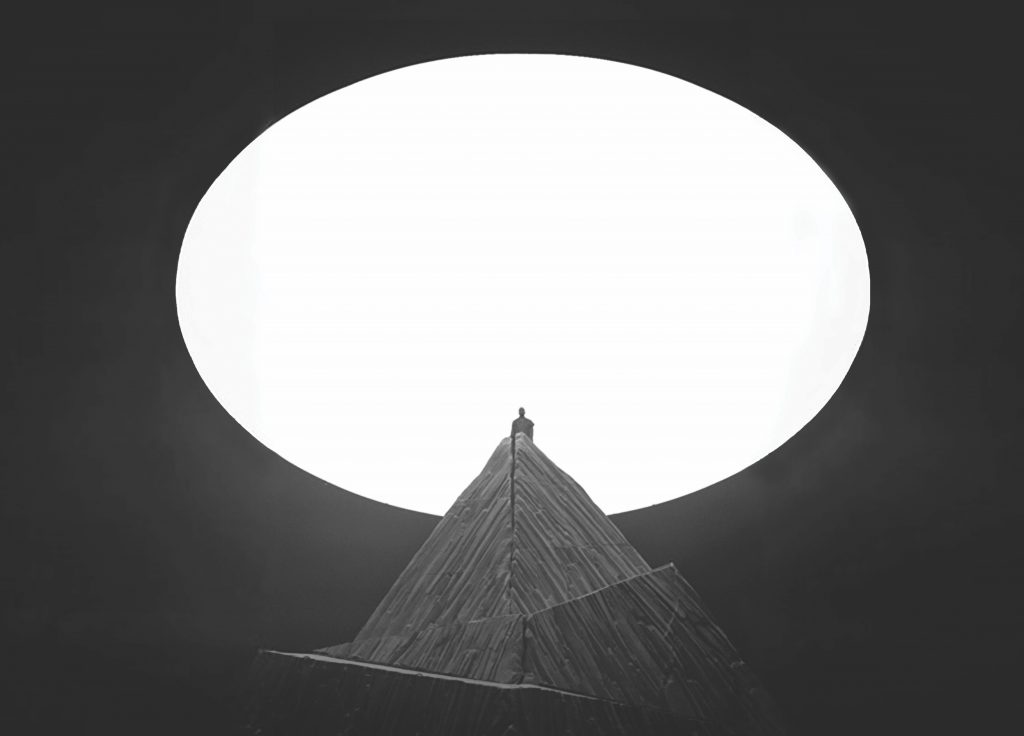

We’re working on the Golden Tower of Ascension right now—a tower that’s also a park. We look out the window and there’s an empty space, so we decide to put a tower there. It will be about 40 stories in height, but only about 10 floors. The floors are very tall in between because it needs to feel open. It’s because in Chinatown there’s not a lot of green space, not a lot of nature, not a lot of public space and it’s all very dense. We’re basically trying to bring a lot more public space in Chinatown.

I had this conversation with our studio director at the beginning of the year—what’s our business development strategy, typical office stuff. We’re talking about it and I say I’m actually really bad at going to fancy parties and schmoozing to find a client. But what we are really good at is actually putting out ideas, compelling ideas, and now we have tools that allow us to put them on the road. So we decided not to do business development and instead just make ideas that are convincing.

Images courtesy of Design Indaba + FOOD