Interview: Designer Es Devlin

Design Indaba 2018’s keynote speaker on the process of creating a visual voice

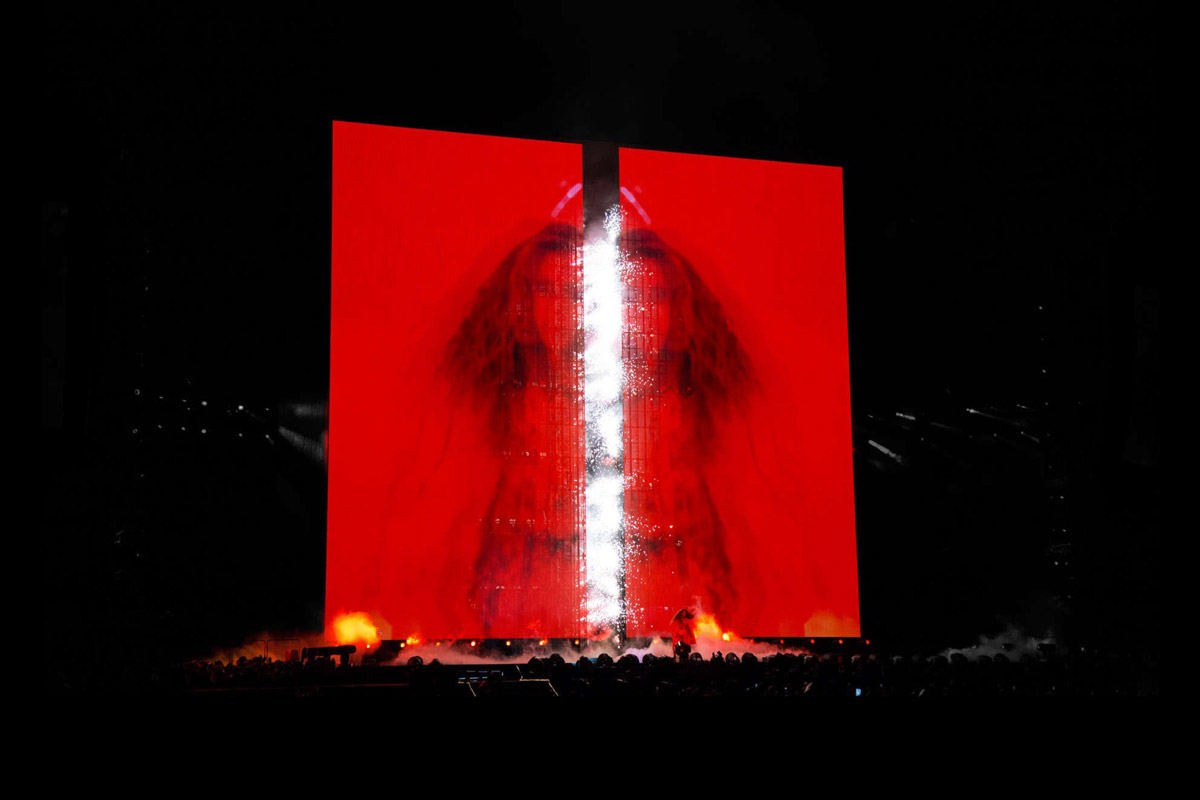

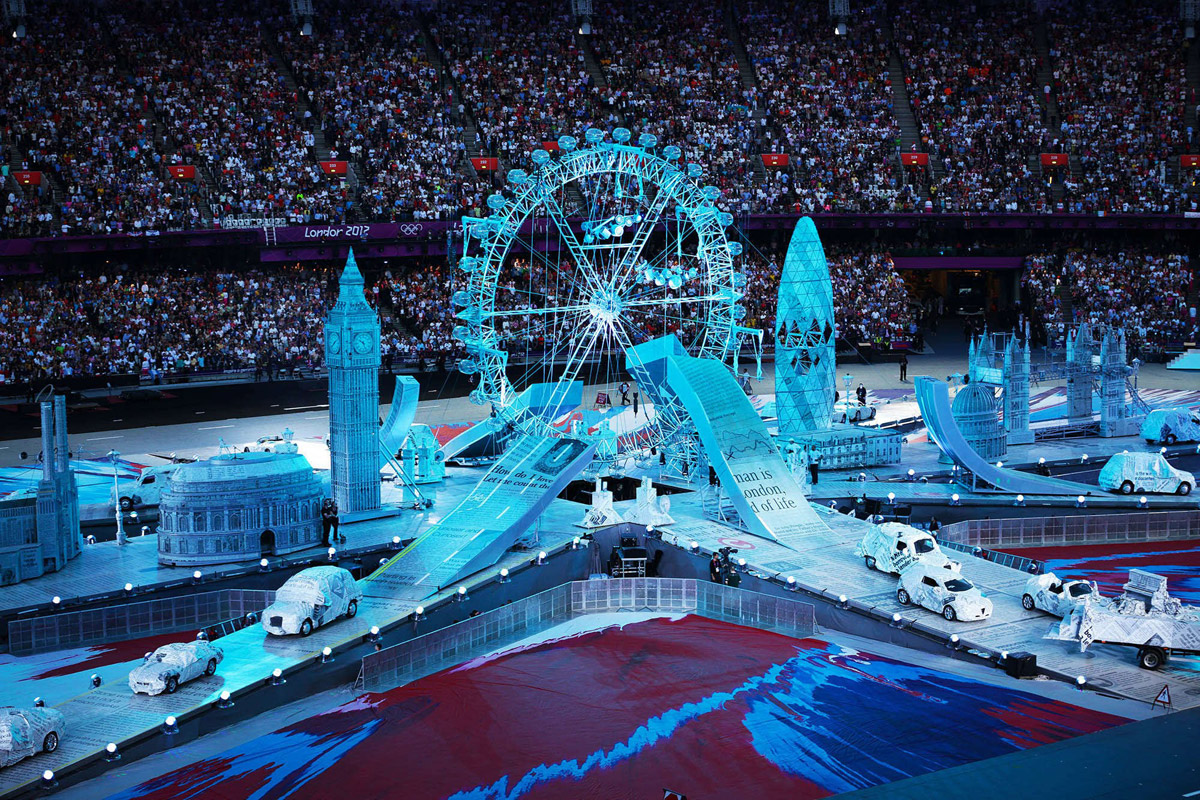

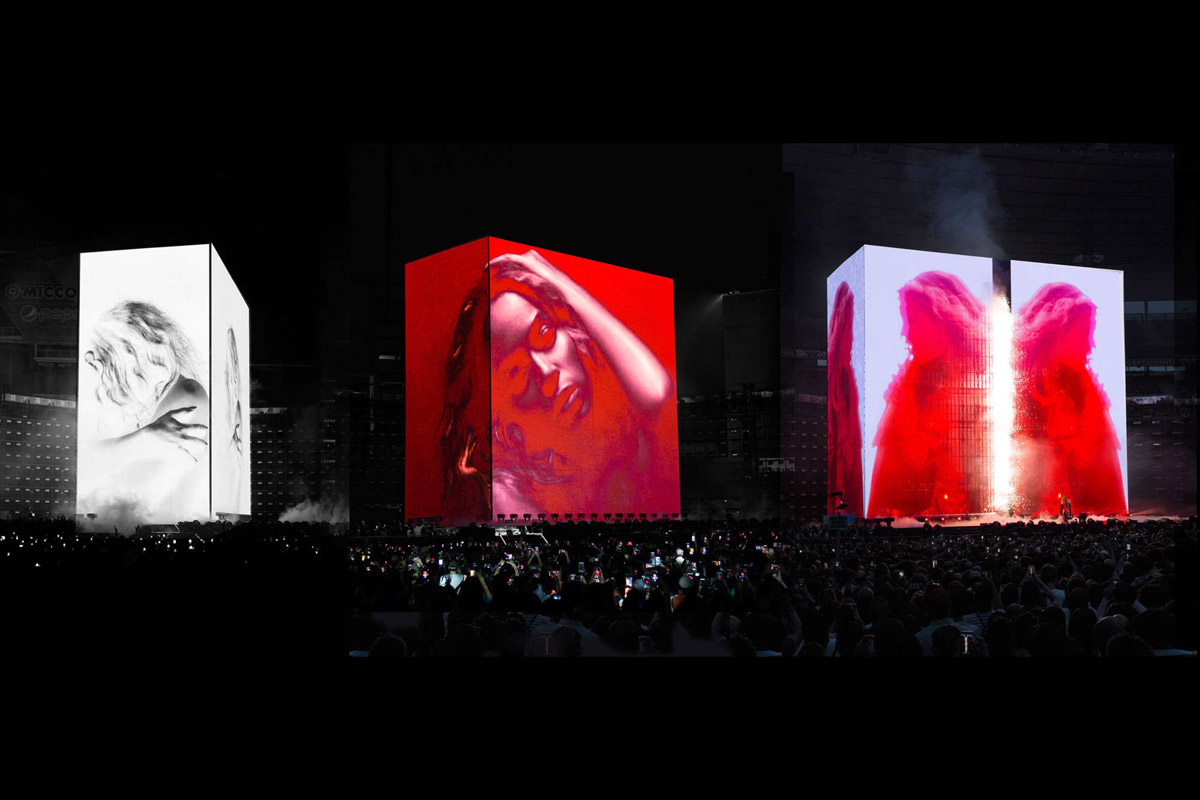

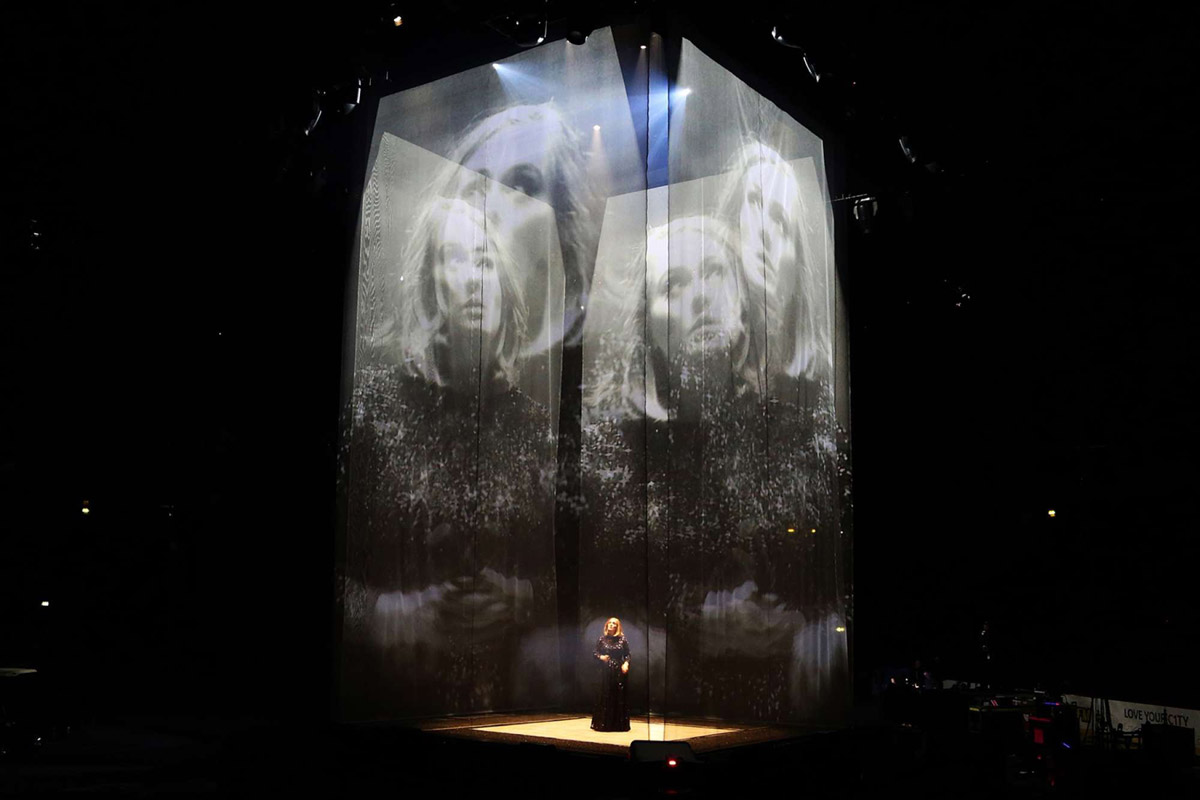

Es Devlin played the violin while growing up in East Sussex. But, the British designer told the crowd at Design Indaba’s recent conference, she also drew pictures of her violin. With instruments, she was always curious about “what went into it visually to make it sound like that.” After her career designing sets for experimental theaters in London took off, she returned to thinking pictorially about instruments, but as they related to human vocals. “I was keen to see, ‘Is there another way to translate from a singer’s voice to a visual manifestation of that?'” Devlin has since become the go-to designer for artists seeking what she calls a visual voice. Her remarkable talent for building such an instrument has seen her create sets for Beyoncé, Kanye West, Adele, and the Olympics in both Rio de Janeiro and London. Dedicated to her craft, she continues to work across disciplines and collaborate with fashion designers, theaters, museums and more.

Her keynote talk at this year’s festival shed light on the real depth of her work, which she equates to something else she learned from playing the violin: the importance of practice. She noted, “Doing it again and again means you get better; the word practice isn’t just about rehearsing, it’s about understanding that the rehearsal for your life is your life and your daily practice to get better becomes your practice, becomes you.” We sat down with the artist/designer/stage sculptor to learn more about her creative process.

Tell us about holding onto Bob Geldof’s foot at your first-ever concert.

I didn’t think about the look of it. It was all about intimacy and proximity, being near the voice. My relationship with the voice was just, “I want to touch the voice, how can I touch the voice?”

And did the voice match what you had expected?

No, you know, the problem was the sound was shit and the voice wasn’t the same as it was on the record. You loved the difference because it was real and it was live, but it wasn’t what you expected. So it was at once disappointing because it didn’t match what I’d heard on the record, but it was immensely rewarding because I was close to the source of the voice and my instinct was just to reach out.

What’s been the hardest thing you’ve done career-wise?

Probably the more collaborators I have, the harder it gets. The more potential for dilution there is and the more potential through dilution to humiliation. To still have my name on something and know that it’s been so diluted through collaboration; projects that fall within that category are the ones with a lot of voices, the Olympics would be one. I’m really glad I did it, it was a really fun time in London, but in terms of the work it’s a long distance from the initial intent.

In terms of collaboration, do artists come to you with an idea or do you present to them?

Ultimately, it’s all their voice, but when I don’t do peoples’ shows they look different, so I guess what I try to do is I bring my voice into their voice. It’s a meeting of voices. Their medium is not visual—it kind of is to a degree because they’re a fine artist as well, but a lot of the musicians I work with, their medium is music, so I am translating from their core medium into what is mine. I’ve had more than 100,000 hours making visual things, where as obviously, I wouldn’t even dream of singing a note. So I think there’s a sort of understanding of hierarchy and equality there. I never feel like I have a boss.

Is there anything you’d like to do that technology hasn’t caught up to yet?

Yeah, I don’t want screens anymore. I want to make films in the air. (Don’t we all?) It’s becoming more possible. You can hold your phone up and, on a trigger, if you look through your phone or through the glasses, you’ll see film scenes happening in mid-air. I’m not sure quite why, but in a minute that will feel as normal as watching a film on a screen. It would be wonderful because it would be behind the artist and in front of them; it would be around them.

Is your process different in designing for a pop concert compared to a theater production?

The process is not that much different: understand the voice, read the words, enjoy what the visual manifestation or augmentation or environment around the words should be. The difference is in the reach. I’m a little bit like Adele saying I want the message to reach people right away. The refinement I can achieve in a theater is way beyond the refinement I can achieve within the parameters of a touring rock ‘n’ roll concert with all the collaboration time, dilution, parameters and logistics. I can achieve so much more in terms of perfecting the sculpture. I could make much more beautiful things if I stuck to theater and opera, but who the fuck would see them and who would care?

Are you a person who seeks inspiration, or catalogs it? Do you look at other work?

None of the ideas that I have would’ve ever happened if I hadn’t drunk the culture around me, like nutrition through culture. I’ve been lucky in London, I see everything. Now with Instagram, I see everything. I draw, I hopefully digest, and everything goes through my person, I hope things I make don’t look derivative, but everything stands on the shoulders of everything else—of art, of day-to-day life, of my kids, of their stuff, of films. I’m a junkie, a culture junkie. I live for it. The older I get, the more I live for art and culture.

Did your work or the way you think about work change after having kids?

It got better because time became more precious. I became really fast; “Gotta get it done, got to feed the baby.” You just get more efficient and better, and also you have this extraordinary time where you stop working weekends to be with the kids. If you’re quite fastidious, if you’re a person who wants to do things well, then you will want to do parenting as well as you do work, so your commitment to your work won’t falter, but you will only have that many hours in your day and you’ll want to show your commitment to being a parent. So what will happen is you’ll stop working weekends and start putting your children to bed at night.

Most concerts are at least 90 minutes long. How do you sustain the excitement?

It’s really hard. And normally you don’t, right? They start great and then they go a bit shit. I have to say who is really brilliant at that is Willy Williams, the creative director for U2, who really is a master craftsman of the arc of a show. I do my best to start with the audience anticipation as the prime material. If you think of a rocket, that’s the launch, that’s what gets it off, so don’t fuck that up. Do not squander it, meter that out. Don’t deliver the artist straight away.

First, deliver a glimpse of the artist. Start with a shadow or a film of the person—anything but the person. Then delay and deliver finally the person, but bring the anticipation to the max. Let the audience feel like they’re the rocket making this thing go off. And then it’s like an aircraft on a flight path, once you’re up you have to not let it come down. Then at a certain point you have to take it to climax and you have to crash it, and let everybody feel the misery. Neil Tennant said to me, all gigs are the same shape; they’re like an amazing Saturday night out with tears in the toilet and the redemptive finish. And Bono would call it a cataclysm with a redemptive ending, you know, different performers who have gone out and felt it every night, they know what the arc of the show is, and it is a flight path. You have to just be sensitive to the flight path and place the songs—the running order is critical. I’ll work closely with the music directors who know the work in and out in terms of the key changes and when you modulate from one song to the next.

What’s the downside to your craft?

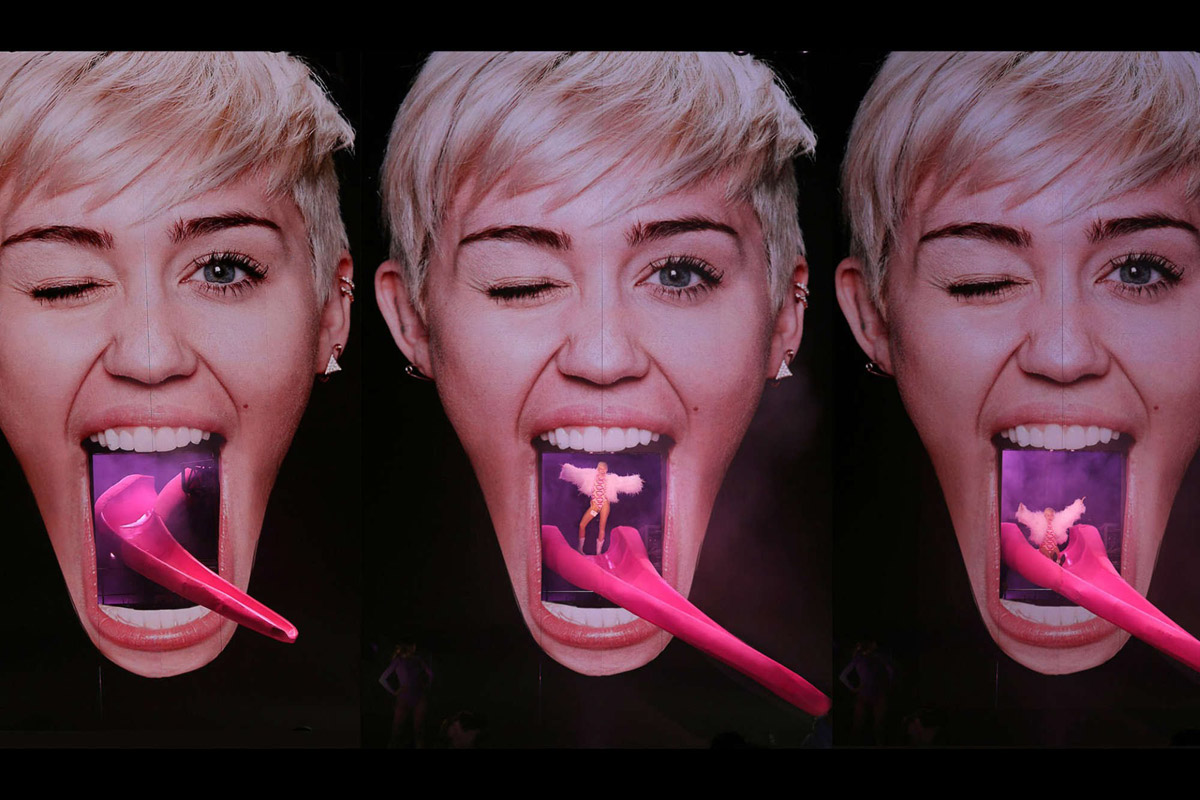

Humiliation. If you’re a designer, if you’re someone who’s been used to making things to a certain level of your own personal standard, what is visually right or wrong, when you make things of all conscience that you know are visually not good enough, they don’t meet your own rigorous standards but that you know is the right gesture, you remain scarred by the fact that gesture in the parameters couldn’t be realized to the correct level of execution. You don’t want to abandon the gesture because you know the gesture’s right, in the end, fuck it. Getting the right gesture is more important than getting the perfect level of execution. And I think there’s an equivalent need just in gestures that needs to be communicated to people. If I need Miley Cyrus to come out on a tongue, it might be a bit shit, but it’s fucking great. It can be a bit shit and be great, right?

Do you have any dream collaborators?

Often it’s music I didn’t know before. I’m obsessed with music. I’m working with ABBA at the moment which is polyphonic, choral harmonies that I love. I’d love to work with some more big choirs. I love layered choral music, Bulgarian choirs, African choirs. I’d love to work with many voices. I just get moved by them. The older I get, the more I just want to be moved. Wake me up, please move me. Please move me.

Images courtesy of Es Devlin