Fernando Mastrangelo’s Supernatural Lounge for Audemars Piguet at Art Basel Miami Beach 2019

Interpreting the manufacture’s Vallée de Joux home with curious textural materials and gradient tones

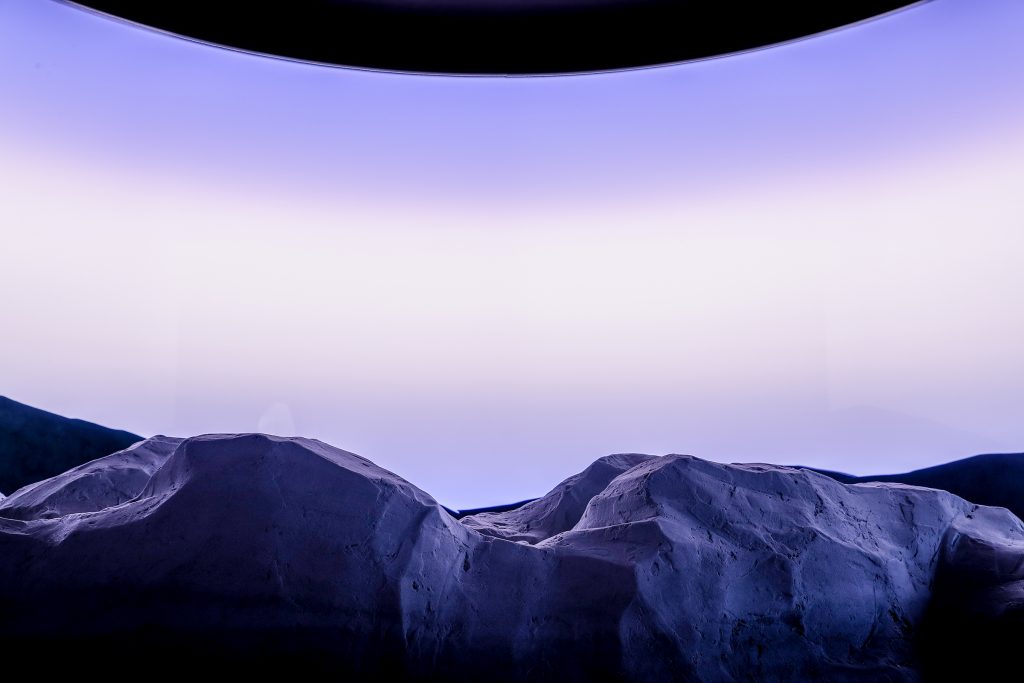

Stretching within the collector’s lounge of Art Basel Miami Beach this year, sculptor and designer Fernando Mastrangelo‘s booth for Audemars Piguet invites attendees to leave Miami for a supernatural visit to the Vallée de Joux. Mastrangelo, whose work often segues from elevated concepts to curious materials, manifests a spruce forest from crushed boulders and glass watch displays—and couples it with an “escape room” that utilizes programmed LEDs to emulate his observations of a sunset in Switzerland. Mastrangelo oftentimes weaves in metaphor, and here he even translates components from Audemars Piguet‘s Code 11.59 watch collection into fundamental, experiential attributes.

Prior to the fair, we ventured to Mastrangelo’s 10,000-square-foot studio space in Brooklyn‘s East New York neighborhood. There—among various components, occupied staff members, and completed pieces—we spoke with the designer about his career as a whole. It became evident that through all of his projects, Mastrangelo aims to imbue greater significance through a harmony of materials, the idea they’re in service to, and ultimately the final form.

At this point in his career, Mastrangelo has transitioned from sculptor to designer, but the two go hand-in-hand. “I’ve always been making sculpture,” he tells us. “When I started making furniture, I did not change my approach. I found ways to express myself in furniture that were not too dissimilar from ways I used to express myself in sculpture. The fact that the end result became something we understand as a chair or console—that really isn’t important. I still express myself the same way. That’s why furniture design ended up being an extension of my sculptural ideas.”

He’s observed growth in the collectible design category—and in an audience that’s starting to crave furniture that is also art. “This is still a fairly new concept,” he explains, “especially to art collectors… Consumers likes to assign value to things. If you are trying to sell a high-end piece of design, that’s also conceptual—you have to explain why. If you are buying a painting from an established gallery, the value has been established by the institution itself, and the market. With design, this hasn’t happened entirely.”

When I consider materials, I use them as a way to make work conceptually more interesting

Understandably, material—and Mastrangelo’s approach to it—can help define or disrupt value. “I use salt quite a bit in the studio,” he says. “Salt, to me, has inherent content to it. It was used for a long time to preserve food. It also has a destructive quality. It can make things erode. It has metaphors built in. When I consider materials, I use them as a way to make work conceptually more interesting.” And yet, salt (as well as sand, sugar, cement and more of his frequently used components) is inexpensive and commonplace. Thus, their value comes from radical elevation. “If you can use a low-end material and transform it beyond imagination—through craftsmanship—and the end product’s surprise, it becomes something extraordinary,” he says.

“In general, I’ve been thinking about this a lot: what meaning and value do artists bring besides market,” he continues. “Are artworks cultural signifiers of our time today? Why would we continue to create sculpture and paintings unless there was a market?” There’s a skepticism to Mastrangelo’s considerations, and they reflect the professional transition he’s made from art to design. He acknowledges, however, that it is through sculpture that he learned how to imbue meaning into design, and this elevates that which he produces.

“When you get to the tipping point of your career in sculpture, you’ve created a recognizable language. What you make isn’t just a discreet object anymore,” he continues. “This language can carry over brilliantly to design.” While Mastrangelo can be moved to work within design or sculpture at any given moment, his passion is in design first and foremost. “It’s a natural state of being for me to ignite my creativity there,” he says.

The partnership with Audemars Piguet (a brand that has followed his work for some time before initiating the commission) enabled Mastrangelo to explore an architectural side he wouldn’t have had otherwise. These opportunities are important for a self-sustaining studio. “I haven’t had gallery representation for about seven years,” he says. “I was able to leverage the rise of social media. I get direct inquiries. Brands reach out via Instagram. I’m doing a YouTube show to explore that audience, too. We are in an attention culture and that’s where opportunities come from: gathering people’s attention. Altogether, we are trying to figure out what the future looks like for an artist studio. For me, that’s survival.”

Courtesy of the artist and Audemars Piguet