Interview: IndyCar Driver James Hinchcliffe

We take the track with the Schmidt Peterson Motorsports driver to learn about training for the greatest American race spectacle

by Ryan McManus

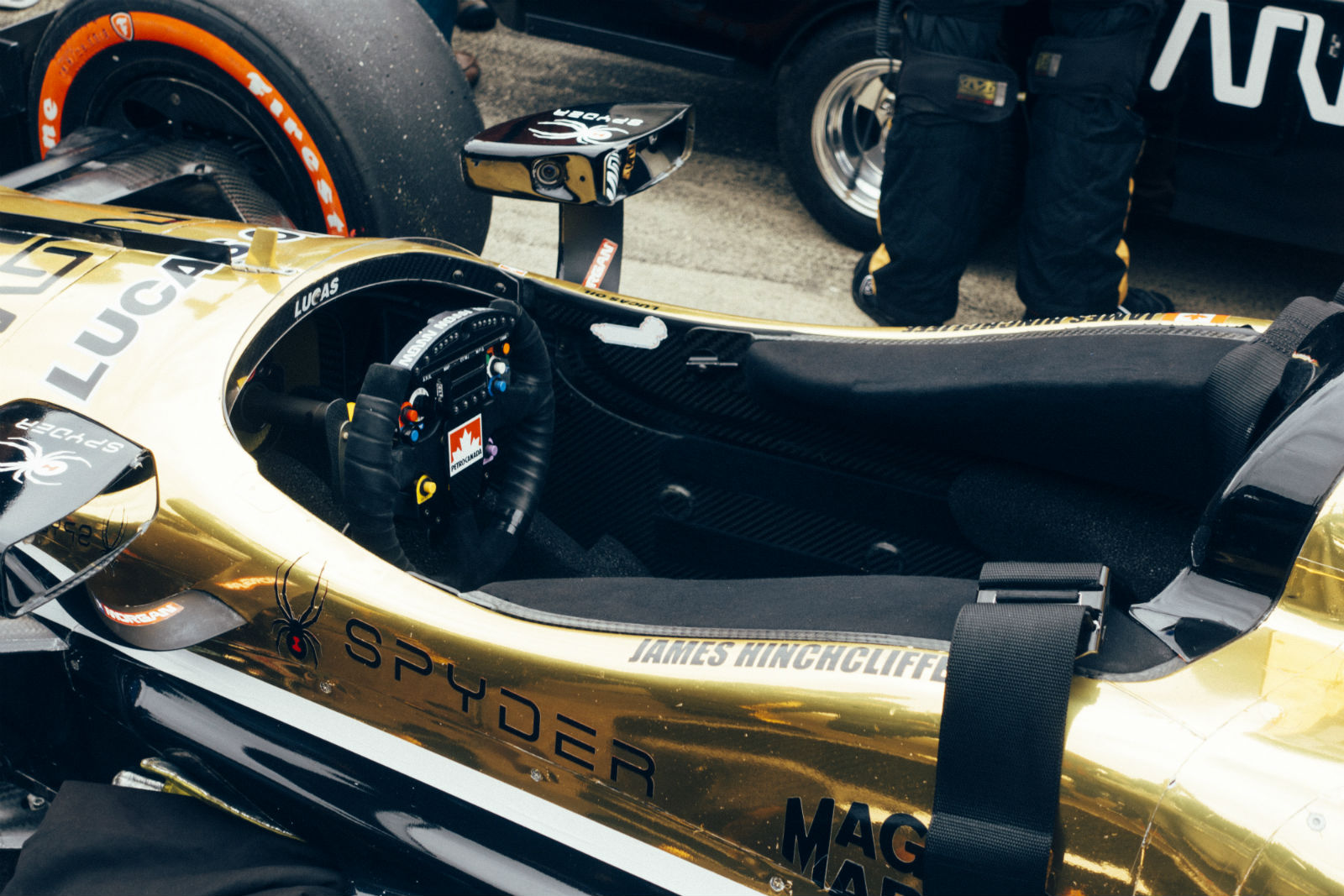

This Memorial Day Weekend marks the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500, the crown jewel of American motorsport. Despite expecting to draw crowds north of 350,000 on race day, IndyCar remains on the periphery of the average American’s motorsport awareness, eclipsed by NASCAR and the Sprint Cup. I went down to Speedway, Indiana ahead of the 500 to talk with Schmidt Peterson Motorsports driver James Hinchcliffe, who earned the Pole Position for this weekend’s race, to experience the track from inside an IndyCar, and to understand why the Indy 500 is still called “the greatest spectacle in racing.”

I arrived at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway at daybreak, the sun fighting through some ominous low clouds. It had rained before dawn, and stretches of the track still glistened. The facility at rest is like some kinetic brutalist sculpture, mixing concrete utility with an arching, mathematical grace. Even mostly deserted in the morning chill, the place buzzes with the energy of the hundreds of races that have taken place over the years, the drone of furious twin-turbocharged V6s still echoing here even while it sleeps.

Helmeted and fire-suited, I climbed into a specially designed two-seat version of the spec IndyCar. My driver Martin Plowman swiftly pulls out of the pit lane and onto the track (today, configured as a road course), blipping the throttle to warm the tires against the morning’s persistent chill. Having only spent track time in cars with enclosed cabins, the differences of an open-cockpit layout becomes rapidly apparent: this is a far more physical endeavor.

Despite being tightly cocooned in carbon fiber, I feel every burst of acceleration as a shove to the chest. The wind passing over the car is trying desperately to yank my helmet off. The vibrations and the sound of the engine fills every atom of space around us. Before I know it, the long straight ends in an abrupt 90º right turn. The rapid-fire downshifts are incredibly violent, snapping my head forward in staccato as each turn approaches. As soon as we hit the long right turn of the oval, Plowman nails the throttle and holds it flat-out through the curve, and I find myself wanting to shout in exuberant joy to the team in the pit lane as we rocket past.

Stepping out afterward, it becomes exceedingly clear how difficult piloting one of these machines must be, and also how absolutely addicting. Two laps around the track as a passive participant have left my hands shaking with adrenaline, my mind in a haze. Trying to imagine driving flat-out for 500 miles, struggling against gravitational forces to maintain composure and execute strategy with 32 other drivers inches away all trying to do the same thing… well, I realized I needed to talk to Hinchcliffe.

I made my way back down Gasoline Alley and caught up with Hinchcliffe as he was prepping for the day’s Grand Prix of Indianapolis, a road-course race that serves as a lead-in to the Indy 500. Hinchcliffe has become the de-facto face of IndyCar in recent years, as he represents an almost perfect Venn overlap of the effortless cool of F1 drivers like Senna and Jacky Ickx and the everyman appeal of fan-favorite NASCAR stars like Carl Edwards and Jeff Gordon. While team mechanics made last-minute adjustments to the cars, we spoke about his love for this sport, what it takes to become an elite driver in IndyCar, and where he hopes to see the league in the near future.

As a driver, what do you find is the toughest to convey to people about your job? How does the average fan comprehend how difficult driving an IndyCar can be?

What’s so hard for the average fan to understand is just how hard it is to drive an IndyCar, because they can’t really relate. Anyone can grab a basketball, stand at a 3-point line, miss nine shots out of ten and realize that Steph Curry is really good at his job. But the only thing people relate to driving a race car to is driving a road car—going to the grocery store, going to work—which obviously isn’t that hard. So it makes it an extra challenge to explain to people what it is that we’re doing, and what it is that we’re going through, never mind how hard it is to actually do it.

As far as the physicality of the sport, you mentioned that it’s a mix of the cardio abilities of a marathoner on top of a ton of strength training. I was wondering if you can talk about what your training regimen looks like?

Our training is pretty complex, to be honest. We do a vast mix of strength training and cardio, a lot of upper body work for sure. Core strength is incredibly important. We also tie in a lot of reaction training into it, because obviously reaction times are key when you’re traveling at 200mph, and we want to make sure that the mind and reactions stay sharp even as the body begins to fatigue at the end of a race. So we’ll mix in some high-intensity circuit training, some high intensity cardio, with trackable reaction training. We have a computer that monitors every session we do with the [reaction tracking] machine, and we can see if our scores are going down as we get more and more tired. We try to make it fun—we mix in things like rock-climbing which is incredibly good for grip strength, and we do a lot of swimming, a lot of biking. It’s a full-body workout, six days a week, two–four hours a day.

How did you start racing? Where did you begin? What was your first race like? Your first win? Your first big mistake?

I started racing when I was nine—my Dad is from England, and so I didn’t grow up with the traditional Canadian influence of hockey, I grew up with a motorsports influence. We watched racing from as far back as I can remember, and for my ninth birthday I got a go-kart. My first race was kind of terrifying—I was young and didn’t really know what I was doing, didn’t really practice a lot. We just kind of jumped in the deep end. And I’ll be the the first to admit that I was crap, I was no good the first time I sat in a go-kart. But I loved it, and was determined to get better. My first year, I came in last every single race, and I remember the first race where I didn’t get lapped was like a mini-win for me. We came back the next year and the very first race of the next season I won my first race. I’ve made many mistakes. I remember my first big crash when I got up into cars; I was running the Formula BMW series in 2004, it was the last race of the championship, and in practice I had a pretty massive shunt into the wall in turn six at Laguna Seca. It’s one of those things that’s part of racing, that’s part of learning, and you kind of have to learn to get over that and get back on track.

Can you talk about how you’ve come back from your accident in a year? How do you get back behind the wheel, both physically and psychologically?

For me, the only challenge in getting back in the car was the physical side, because obviously I had to sit around and wait for my body to heal, and as I sat around I lost a lot of my fitness. And so it took a tremendous amount of hard work to get back to a level that was required to race IndyCars at this level and be competitive. So it was a lot of long days, a lot of painful sessions in the gym and in rehab, but my determination to get back was way stronger than any physical discomfort I was feeling. Psychologically, for me, that was the easy part. I never once wavered in my desire to get back behind the wheel. My third question after waking up was “When can I get back in a car?” Not having any memory of the accident itself makes that easier, no doubt, but the minute I woke up I knew I was going to get back in a car.

What are your hopes for IndyCar in general? How do you expect it to change in the coming years?

My hopes for IndyCar is that it regains its position in the grand scheme of sports in this country, and in North America. Not that long ago, IndyCar was one of the most-watched sports, one of the most exciting sports, and it’s still one of those two things. But obviously now there is so much competition for people’s attention, for people’s recreational dollars—whether it’s going to games, going to concerts, or coming to races —there’s just so much more competition. Our sport and the product has only improved over the last 20 years, and so I really hope to try and help get that message out there and show people just how exciting the sport still is, just how good the racing still is, and get us back to where we were, and where I think the sport really deserves to be.

What was your first car? Your all-time favorite? What’s your current daily driver?

My first car was a Mini Cooper S—my dad, growing up in England, his first car was a ’59 Cooper, and he got nostalgic when BMW reintroduced the car back in 2003, so he just kind of bought one on impulse. And he already had a car, so it just sat there. I got my license at 16, and just before my 17th birthday I was sort of borrowing the Mini all the time, and one day I borrowed it and never gave the keys back. So I sort of inadvertently inherited a Mini, and that car was an absolute blast. I have another one now, I went out and bought another one because I just love that little car. It’s great.

My all time favorite is a tough thing to answer. There are so many beautiful cars out there, so many that I haven’t had the chance to drive yet that I’d love to, and definitely a lot that I haven’t had a chance to own. There’s definitely more cars that I want to drive than time or money to drive them. My daily driver is an Acura MDX—it sounds boring, I know, but it’s a great little car. It’s bulletproof. I’ve got a pretty strict rule right now of not spending a bunch of money on a supercar that’s going to make it that much more likely that I lose my license. My status in this country is very temporary, and I certainly don’t want to give anybody any more excuses to kick me out then they already have.

Are there other classes of racing you’d want to try? F1? NASCAR? WRC? Drones?

Well I’m not sure about drones, but pretty much anything else! As long as it’s got four wheels and an engine, I’m down. I’ve had some talks about trying to get into the NASCAR Xfinity Series to do some of the road course races, and it’s fascinating to me how different that machine is from what I’m used to driving in IndyCar, and would love the challenge of getting into one and trying that out for a few races. Formula 1 is the pinnacle of technology in racing for sure—the cars are very impressive, the tracks they race on are cool, but for me the lack of parity makes it tough to motivate yourself as a driver, I think. You see one team that dominates, and you know as a driver that on any given day, depending on the team you’re with, you’re going to finish somewhere between 8th and 14th. That just seems like a tough way to motivate yourself to go to work in the morning. For me, IndyCar really is the best all-around series. I like the diversity of the tracks, I like how close the competition is—it really forces you to try and be perfect every single weekend, and I really like that challenge. I’ll try anything, but I’m really happy where I’m at.

Experiencing a race firsthand, we were awestruck at the sheer accessibility of the sport from a fan perspective. Before the Grand Prix began, hundreds of fans were mingling on the track with the drivers and their teams, pausing to take selfies and ogle the cars. At several points we were within arms’ reach of a driver who was about to spend hours in a highly specialized machine, yet they shook hands and laughed without a hint of elitism. We made our way over to team Schmidt Peterson, and caught Hinchcliffe giving a double thumbs up for a fan taking a photo on her smartphone. She’ll likely be a fan for life, and if most people could experience the sport the way we were able to, they would be, too.

Images by Ryan McManus