Interview: Afroditi Krassa

The interior designer on the true meaning of sustainability, gender politics and how she works like a chef

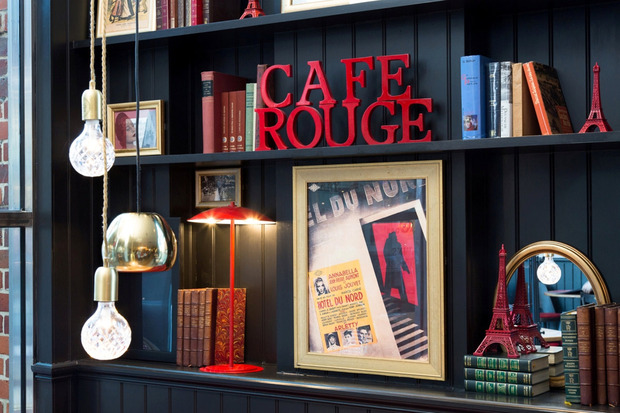

Based in London, with firm roots in Greece, Afroditi Krassa has established herself as a prominent designer of her generation—particularly in interior design. Her clients range from the highly lauded furniture design house Ligne Roset to Italian interiors leader Bonaldo, from Cassina IXC to mainstream clients like Topshop. Her studio is behind some of the most awarded restaurant designs of the past few years including London’s Itsu, Café Rouge, Oriel and vintage-style Indian café Dishoom. CH met Afroditi and discussed being a female designer in a male-dominated industry, the true meaning of sustainability and the evolution of the food frenzy.

How did your start your career in design?

I studied product design at Central Saint Martins because I loved the whole idea of working in something very creative. But when I started working I found the world of commercial studios extremely uncreative and I couldn’t see myself loving what I was doing on a daily basis. It was all about getting as much work done as quickly as possible. It became anonymous as well, and also very much about styling and resurfacing objects. I worked on highly commercial product designs, like watches, cameras, mobile phones. It was basically beautiful technology on the inside we had to box up with a different aspect every time. I thought there was no research, no time to understand, no time to disrupt or really think of something new. It was only about the surface of things, not about the core of things. It was styling, so I decided to leave.

I went to the Royal College of Art of London to do an M.A. and I knew from the beginning that I wanted to setup my own company. I had fantastic tutors like Konstantin Grcic, Jasper Morrison, Sebastian Bergne, Tord Boontje, Ross Lovegrove; the top of the top-tops—it was a star lineup of tutors and teachers. I graduated and set up my own studio and the main reason was doing what I really wanted to. I’m not against the idea of having commercial clients, but I think it’s really important that there are parameters to what you’re doing; that there is a brief, and a precise budget. If you have constraints, sometimes these are the most challenging and interesting projects. If the client says, “There’s no budget, do whatever you want,” it becomes self-indulgent. I love those kinds of challenges and I don’t mind that as long as the constraint is not on the creative side.

Can sustainability be one of these constraints?

Absolutely, yes. Although I think that sustainability is very complex, a difficult kind of world. Shigeru Ban, the Japanese architect, recently said that he hates the word “eco,” since it’s a marketing term that everybody uses, but nobody really understands. He said it should be all about finding new materials and using them in an interesting way. I think ecology is not a fashion; it’s a real issue. But the problem for designers is that we’re not educated and actually it’s very hard to access what’s truly sustainable and what’s not. You almost need a doctorate to be able to understand if something is truly sustainable or not.

Today for designers, it’s not enough to think about the birth of a project, you should also think about its life and the death.

Actually, you should think of not even giving birth. That’s the most sustainable approach. The minute you start a design project, it’s by definition not sustainable—you’re creating things that will become eventually rubbish at some point.

How do you approach sustainability at your studio?

We design spaces and I think the best way to be sustainable is working on something that can last for as long as possible. As a designer I’ve never had the experience of seeing one of my designs being destroyed. I know it will happen; it’s just a matter of time. At some point they will go and knock our things down, refurbish it. It’s the natural side of things and I’m curious to see how it feels, because I think that, as a designer, you hope that your work surpasses you, survives you and lives longer than you do.

They told me in the interview I was being employed for three reasons and the first one was being female. I didn’t know whether to take that as a good or bad thing, because I don’t want to be treated in a different way or considered a minority.

Do you think there a “female” way to design?

I don’t know if there is a female way to design, at least not in terms of styling. I’d hate it if our work became female as such, if it was genderized. We’re an all-female studio, which is quite unusual. We’re six women working together, which is not on purpose by any way, it just happened. I don’t work with a signature style of things; it’s totally against what I believe as a designer. I very much respond to grounds, to briefs, to specific problems. I usually tell my clients that people come with the problem and we try to solve it, whatever that problem is. And the response might be completely different every time, but in terms of questioning things, perhaps there is a female way.

Anyway, I think there is a slightly different response when you’re a female in design. Straight up out of college I went to work for Seymour Powell, which was one of the biggest product design agencies at the time and still is. I was their first female designer employee ever, and they were there for 14 years already. They told me in the interview I was being employed for three reasons and the first one was being female. I didn’t know whether to take that as a good or bad thing, because I don’t want to be treated in a different way or considered a minority. A lot of these guys at Seymour Powell were designing products that were used predominantly by women, chosen by women, selected by women. It was like 40 boys designing bikes and cars and other things. They think every car is bought by men, but actually 60 percent of decisions in car sales is done by the females rather than males.

Would you design a motorcycle?

Yes, I would actually. I ride a Vespa, so why not design one? Can we call Piaggio to let them know? But it would depend on the briefing. The product is not my concern, it’s more about the brief and the process as such. You can have the most interesting product or category, but the most boring brief within that. Designing a whole system, rather than an outcome—I would be interested in doing that.

Your interiors are based on reflections, shades, layerings, superimpositions. Can we define your work as an “organized complexity”?

A few days ago I was thinking to which work I relate more to. I do like simplicity, but at the same time I don’t. That extreme level of simplicity, I find it almost unemotional in many ways. Sometimes with our projects we really struggle because we try to connect so many dots. We start from a really, really rich perspective. When we start a new project I sit in the studio for days and just collect, collect and collect—then come up with more, and more and more ideas.

Sometimes I find it harder to edit than coming up with things. The plurality, the masses I find much easier than narrowing down, but it always worries me that perhaps it becomes overcomplicated for people to understand. It’s really important that there’s a clear message at the end, one linear approach that connects everything from many different levels. This layering has always been part of me, from tiny details to the biggest things.

The general perception of your interiors is still organic and harmonious, like it the work done for Itsu.

Also at Itsu it’s always about finding a balance. If your message is all about health and happiness, eating beautiful, the way it looks and the perception of what people see needs to be exactly that. A big part of what we eat is visual, since we look at something and automatically make an assumption about its taste. What was interesting with this project was that we even developed new models of Japanese-inspired food that can become portable. Turning the food into something that people can eat on-the-go was a very interesting exercise.

How do you see the evolution of contemporary food culture?

I think chefs are the new rockstars; I really believe that. We work with Heston Blumenthal and we’re designing his next restaurant. You always have busloads of tourists outside his office in his village, just there to take pictures with him. They don’t even eat at The Fat Duck. If I wasn’t a designer, I’d want to be a chef. I love cooking and I come from a culture of food. I used to cook from the age of 10 and I cook passionately even now. When I used to teach I found it easier to explain the process of design to students by making analogies with cooking. You’ve got ingredients (your materials) in the world of design. Then you’ve got processes, which is like frying, boiling, grilling. In designing it would be cutting, stamping, folding. It’s all about putting things together and creating something new.

The design process is an alchemy, a chemistry that happens somehow when you apply heat, you apply light, you apply other elements and in the end comes out with this combination of all these factors into one thing.

In design, the whole idea of senses and how they often layer each other is under-explored.

It’s a creative transformation of matter in both ways.

And although we think food is very much about taste, it’s actually not. Food is strongly visual. On the contrary, we think design is just visual, but at the same time it’s not. There are other sensory elements in how we experience design that we might see as insignificant, but subconsciously are very important.

I think that in design, the whole idea of senses and how they often layer each other is under-explored. Unfortunately you don’t have many projects in the commercial environment that allow you to go really into depth in this kind of research. It gets ignored because in the end it’s all about how does something look as a picture. From my point of view, when I design environments, the key question is not, “How does it look?” but “How does it feel when I walk in?”

This goes back to the beginning of what we were talking about: sustainability. I think the minute you go for all these other levels, hopefully you produce a design which is more classic, which goes beyond the appeal on the picture. Hopefully you’re designing something that has the qualities to last longer. The more we grow as a studio, the more confident we become, and also the more we have a choice on not working on projects that don’t give us this ability.

Visit Afroditi Krassa online for a closer look at her full design portfolio and info on upcoming projects.

Portrait by Paolo Ferrarini, all other images courtesy of respective venues