Interview: Renato Preti

The founder of Discipline talks refined design with “some Italian tomato sauce”

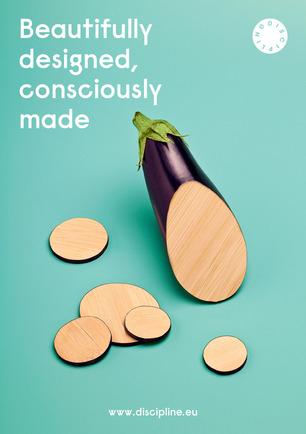

In the panorama of Italian design, Discipline is one of the youngest and most interesting newcomers. Its motto, “beautifully designed, consciously made,” underlines the ambitious goal to meld aesthetics with the consideration of environmental issues from a contemporary and innovative point of view. The mind behind the project, Renato Preti spent years investing in design companies like Moooi, B&B and Skitsch before deciding to start from scratch with his own company. We recently caught up with him for an exclusive interview to discuss good design, sustainability and, as it happened, food.

How was the Discipline project born?

The project originated from a long trip around the world. Last year I tried to understand the common needs of different markets—consolidated ones such as the US, the emerging ones such as China and mature ones like Europe and Japan. This resulted in a series of ideas that have been added to previous reflections on the world of design.

I have long been convinced that the field of design, if faced with innovation, offers great opportunities. Design as we know it today, when it exploded in Italy in the late ’60s, was a highly innovative sector—think about what Mario Bellini, Vico Magistretti and the Castiglioni brothers did. Since then it has gradually fallen asleep, it has become conservative, probably by death or aging of the pioneers, both designers and entrepreneurs.

The shift toward conservatism is in my opinion the very antithesis of the true nature of design. It must by definition be contemporary, based on research and development. For example, 80% of design products sold today from Italy have been designed more than 25 years ago. This figure illustrates how this world has stopped, perhaps because no one wants to take risks anymore, perhaps because inside of the design world everybody knows and controls each other, and this has led to a stalemate. Another example: the two leading groups in the Italian market, Poltrona Frau Group and B&B Italia, make just over 100 million euros per year with their branded products, which is equivalent to the turnover of a single Vuitton store. The volume and numbers of design when compared to fashion are ridiculous. So I think there is a huge opportunity in the sector, but only if you revamp the spirit of the past with innovation and excitement in distribution, product design, marketing and brand identity (which is virtually unheard of in the industry). This sector has simply forgotten to be an innovator.

These thoughts have been with me for many years; for example, when I decided to invest in Moooi, Unopiù and B&B Italia. Those investments have been very positive, but I still had simply a financial role. At one point I thought it would be a good opportunity to make my own company, because—unlike finance—design has always been my passion and it’s my origin too—my father was a small manufacturer of furniture for great architects like Caccia Dominioni and the Borsani brothers.

So I started with Skitsch, but I was in the minority and I did not feel free to make the choices that I really liked. I came out and founded Discipline, which is the result of years of thought and the long trip around the world in which I realized that the market wants two basic things: natural materials and a form of discipline.

What does it mean to work on nature and discipline?

Relying on natural materials should not be intended as a strained search of sustainability, but as pleasure, beauty, durability and authenticity. Discipline starts from these desires. We would never make a product just because it is environmentally friendly, but we’d do it because it is beautiful, lasts longer, is a pleasure to touch—because it excites, makes you feel better, because it gets better with age. The consequence of these choices are infinitely more low-impact, and this becomes a clear choice of sustainability which is realized as a happy consequence of rigor. The proof lies in the fact that we all wear linen, wool, cotton and silk, and refuse synthetic fibers. I do not understand why we should be in contact with objects that have an unpleasant feel and smell, that grow poorer as they get older, that depend on temporary fashions for their intrinsic material quality.

As a second point, we all desire to rediscover some discipline, understood as the search for positive values. Weirdness for the sake of weirdness has bored us and creates risks and problems. “Strange” is fine for breaking the rules when you need to throw it all away, but at some point that has to stop. Design can not live only by bizarre objects, limited editions, imitations of contemporary art and so on. We want to go back to discovering objects with a sense, a function, things related to how they were designed and thought out.

Discipline’s philosophy is described in a manifesto, almost as if we were dealing with a revolutionary artistic movement.

In the noise that accompanies everything we do (business, politics, journalism, entertainment, etc.), either you have something to say, or you’d better stay silent. There is no need for another design firm, another performer or another newspaper unless you really have something very strong to say. With Discipline we wanted to state something and wanted to show it, make it manifest. The manifesto was conceived by me and my staff with great passion and hard work, through an intense exchange that led us to meticulously refine every word and concept. In summary, we have something to say and we are proud to try.

What is the basis for the sustainability of Discipline? What does it mean to be “beautifully designed, consciously made”?

When you address these issues, it’s necessary to clarify where we start—we start with pleasure, and then get to sustainability. We increasingly need emotions, but they should be “disciplined.” Our choice is to not put anything back into the production cycle, using materials that already exist or can grow again, such as wood and cork. We try to use only local materials, and as far as possible the production is completely Italian, except for some glasses that come from the Czech Republic.

We are imagining for the future to concentrate some phases of production at a local level. For example the Drifted stools with the cork seat—the best cork comes from Sardinia and Portugal, and must be worked with special equipment and techniques that are difficult to replicate elsewhere. However, if you send the cork tops to Brazil—they’re lightweight and easily transportable—we can make the legs in place, perhaps using a local wood.

We are not oriented to radical ideological choices (all sustainable, all local, etc.) but we always care about the maximum reduction. One of my university professors said: “Better a soft light than absolute darkness.” If I choose to do everything organic, I risk making low-quality products. If I force myself to go completely local, then the risk is being constrained to choosing the wrong materials, limit the development of the products and not to please anyone. If, however, every time I ask myself how can I reduce weight, volume, waste, time, then I get to sensible improvements, that gradually can lead me to make a real difference.

Take our Kami, a table made of bamboo—it is robust, fully interlocked, no screws, no glue, and can be delivered in a thin box. I have not completely solved the problem of transportation, but at least I can send five in the space that would occupy one single table already assembled.

Since the first collection Discipline has counted on a “dream team” of designers. How did you choose them? Have they been free to design whatever they wanted?

For some aspects designers did not have much freedom. We gave everyone a very clear briefing about the identity of the brand, a 40-page document that was titled “Hello, I’m a new project.” We did not ask for specific products from individual designers, but we gave precise and careful indications about what we wanted in terms of materials and style, but also what we did not want.

I was surprised that the vast majority of foreign designers have responded in line with the briefing, while the Italians have proposed many things that were not consistent: it is an approximation, a superficiality that well represents the Italian condition in recent years. Some even sent us plastic products, when in the briefing was expressly forbidden. We invited about 50 designers: nine out of 10 foreigners have complied with our instructions, nine out of 10 Italians have not done so. In the end, only two Italian designers are present in our catalogue: Mario Bellini, a great maestro and friend, and Luca Nichetto.

From which countries comes the more interesting design today? To which countries does Discipline look?

Surely Japan and countries in northern Europe, but also in London, which is always an interesting crossroads. A summary of what we want to be and what I’d like to develop is summarized in a sentence by Mårten Claesson of CKR: “Our goal is to follow the values and the rigor of Scandinavian design, with the addition of some Italian tomato sauce.” The typical dishes of Italian cuisine are of rare simplicity, but they are masterpieces—everyone likes them, they are healthy, they are based on the excellence of the ingredients. Our spirit is just that, namely extreme simplicity that meets extraordinary refinement. If we’re be able to translate the values of Italian cuisine to Italian design, then we will succeed. Our aim is to thrill through simplicity, to party using the most essential things.

Discipline products can be purchased online and in a selection of the best design stores in the world, like Gallery Bensimon in Paris, The Conran Shop in the UK, Cibone in Tokyo, La Rinascente and Spazio Pontaccio in Milan, Design Within Reach and MoMA Store in New York.