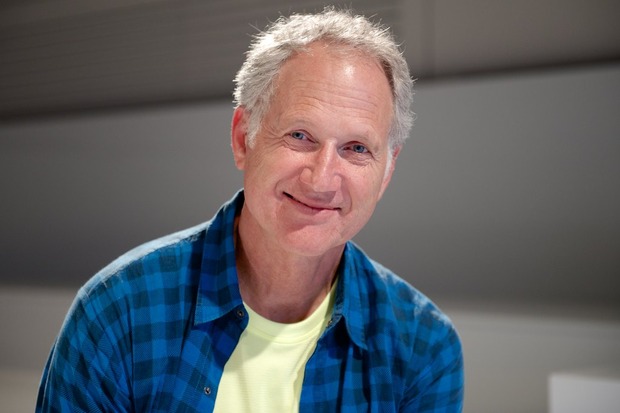

Interview: Tinker Hatfield of Nike

A one-on-one talk with the Vice President of Creative Concepts about facilitating innovation and inspiration

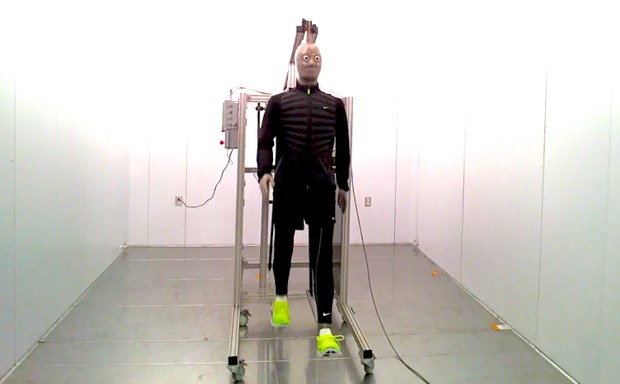

During Nike‘s recent Nature Amplified summit at their Beaverton, OR headquarters, we were presented with a series of innovations that comprise the next palette for product development from the sportswear giant. A visit to the Nike Sports Research Lab meant a deep dive into the methodologies used to understand human mechanics. Of course, all the latest footwear, including the supportive-yet-sensitive Hyperfeel and and the slipper-like Free Flyknit, were observed, handled and tried on. The highlight, however, was a brief one-on-one with Tinker Hatfield, the company’s Vice President of Creative Concepts and Nike veteran of 30+ years.

Hatfield made his start at Nike as an illustrator, but somewhat quickly began designing footwear. Over the years he became widely known for the AirMax and Jordan series of sneakers and earned a cult-level of respect for his collaborations with Mark Parker and Hiroshi Fujiwara on their HTM line of limited edition interpretations of mainline styles. He has always focused on an individual athlete and his/her needs to lead the design direction for a new product, recognizing that meeting their needs would likely result in a product that’s both useful and desirable for a broader audience. Comfortable reinventing his process, today he uses an iPad for sketching and sharing drafts with various constituents.

Upon meeting, Hatfield quickly remarked that my shoes (multicolored Nike Lunar Flyknit HTMs) matched my tattoos. His quick wit and charming personality are infectious, which might be one reason he’s such a great leader. I wanted to know how he manages and motivates such a large design team and how he works with the palette of Nike’s innovations. But I was also curious to find out what makes him tick as a human—not just a shoe designer.

Josh Rubin: Great to meet you, Tinker.

Tinker Hatfield: Your arms match your shoes. You realize that, right?

JR: It’s all planned, yeah. It’s all planned, but the shoes came second. I’ve never actually met someone who got tattoos to match their shoes.

TH: If somebody ever did that, that would be a good story.

JR: I love these. They’re probably my favorite of the year so far. So, I guess where I want to start is thinking about your role in some ways being about the facilitation of creativity and innovation across the company. There are hundreds of designers—it’s a massive design team.

TH: 650. Yeah, a little over 600.

JR: How do you go about that? How do you inspire and facilitate creativity and innovation across such a huge organization?

TH: Well, we have this group called the Center of Design Excellence and they’re really trying to give people some direction, like seasonal direction, but it’s also to kind of remind people what we’re all about. They have, and we have, a way to get information to people via the Nike sponge, there are different design sessions and little design charettes to share ideas.

I like to look at design as being really unique to a particular athlete or group of athletes and really unique to a time and place—rather than a corporate or an institutional kind of mark or direction.

And that comes from John Hoke, who’s our VP of Global Design. It’s his job really just to keep everybody rolling, keep everybody more or less on the same page corporately. But my role is quite different in that I really don’t think of our design efforts as being in a corporate direction. I think, for me, I like to look at design as being really unique to a particular athlete or group of athletes and really unique to a time and place—rather than a corporate or an institutional kind of mark or direction.

So I work more individually with people. I talk about design direction and people come to me, I go to them. My work is quite visible, so people see my drawings and/or maybe hear me speak. I can be a little bit more on a unique, and personal and provocative side.

I don’t sit down and sign-up like 600 people and go, “This is how we design.” I actually, as a designer, never appreciated being too directed by somebody else, so I try to respect that with others. So I wait for people to come and ask me, or I just do what I do and people react to it the way they react to it.

JR: At this point, the palette of innovation that designers get to work from is massive. In terms of the creative process, where do you begin figuring out which of those innovations you want to use, or when it’s time to invent—to create a new thing?

TH: That’s a tremendously important and good question because you know, you have this sort of quarter-to-quarter need to keep and get product in the marketplace that people can use. It works well; it works better than before. And we can get our bookings and anniversary business and then grow. There’s that side of it and that’s kind of, I don’t know—I guess that’s just the hardcore world of business and I think that I try to stay away from that. I used to be in that business where I was trying to work with the business units and design products.

Now, for me in particular, it’s much more about being a part of a more protected innovation society or group—which is the Innovation Kitchen, the Zoo, NAIT in apparel and NSRL. So there’s a little bit of a firewall between that group and the rest of the business. That that group has been given a little bit more leeway or freedom to then invent new ideas. The people who are in those categories—the designers—they’re being innovative and they’re being really creative, but their timelines really suggest strongly that they have to pull from that existing menu.

Mainly we’re trying to create the classics of the future by trying to design really new, new ideas.

So we have that going on and that’s good because a lot of interesting new combinations can occur even with an existing menu of components and ideas. But all the while we have a significantly large group—numbers over like 150 people that are working on what those next ideas are. And they’re both fun, but they’re both quite different. I crossover between the two a little, but mainly we’re trying to create the classics of the future by trying to design really new, new ideas.

JR: What is something you’ve never designed that you would like to design?

TH: Motorcycle.

JR: That’s great! Previously you’ve mentioned Renzo Piano’s architecture as inspiration for the original Air Max, is there an architect right now who’s inspiring you?

TH: An architect? There’s one who’s no longer with us who I go back and look at his work all the time—and he’s not that famous. He was a professor of architecture here in the United States, and his name is Sam Mockbee.

What was great about him was he had a great sense of design, and architecture in general, and he was teaching—in Alabama. He would take his students into the rural parts of the southern part of this country and build homes for people. They would use materials that were available, that were inexpensive, or they could just find. And they would build these incredibly beautiful pieces of architecture for, for example, a poor family living on share cropping.

I’m really inspired by not only his—I guess you could say—philanthropy, but his ability to design, and have the students design, and then build real stuff for real people. It’s extraordinary. I would encourage anybody to look him up.

JR: Yeah, I haven’t heard of him. That’s awesome. I definitely want to check him out now.

TH: He’s been gone about, I’m gonna say six to eight years, but I still look at his work. Sometimes you can pull up some big fancy names in architecture, but he’s special.

Sneaker image courtesy of Nike, all others by Josh Rubin