L’uomo che Firma il Legno

A rare look inside the studio of master woodworker Pierluigi Ghianda

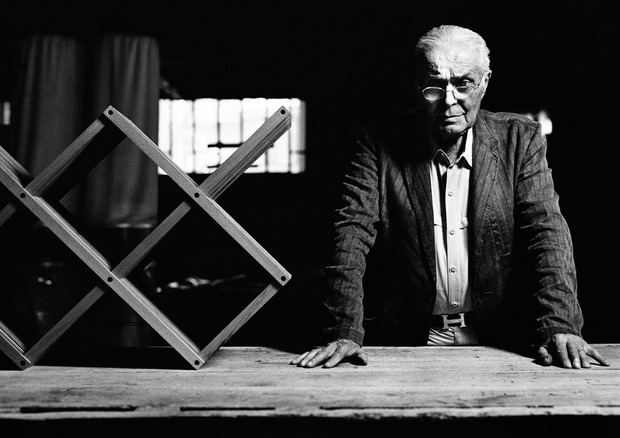

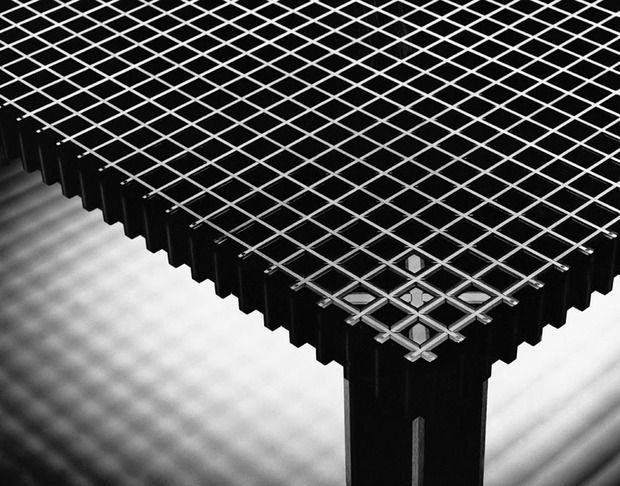

Pierluigi Ghianda, known to many as the “poet of wood,” has in his career left an indelible mark on the world of design. The master ebonist was born in Brianza, a region that is considered the real factory of the Milanese design—if Milan can be considered the head, Brianza is the hand. His experience in craftsmanship was pivotal for the success of products by Gae Auelnti, the Castiglioni brothers, Ettore Sottsass, Massimo Vignelli, Bob Noorda and Aldo Cibic, just to name a few. Recognized among his peers for an innate ability to understand wood, Ghianda is a master of realizing simple but unexpected solutions to apparently impossible design conundrums.

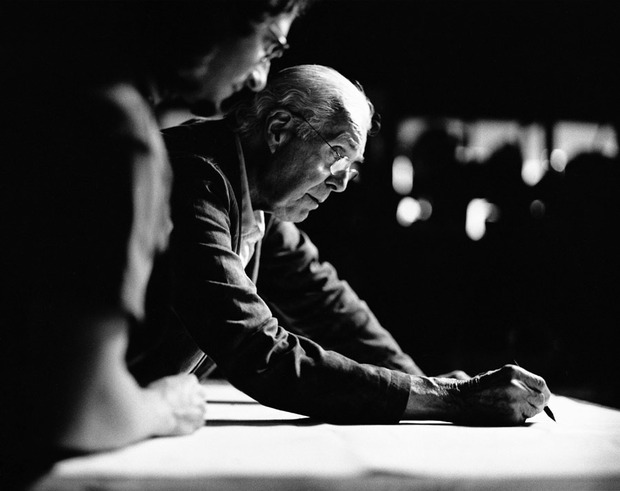

Italian design firm Studiolabo has spent the last few years filming Ghianda at work in his unique laboratory for the documentary entitled “L’uomo che firma il legno.” Translated to “The man who signs wood,” the film aims its lens at Ghianda’s breathtaking skill, as well as his traditional practices in serious risk of disappearing. To learn more we caught up with Studiolabo founder and the documentary’s screenwriter, Cristian Confalonieri.

How did you meet Pierluigi Ghianda?

I was born in Seveso, in the heart of Brianza. In the postwar years, this area had the highest density of carpentry in Italy, and, I assume, beyond Italy. In this area of high craftsmanship even large design firms were born—those that helped create what we know as “Made in Italy”. In this context Pierluigi Ghianda is considered the master. We were lucky—the father of my copartner Paolo has worked in the Ghianda workshop for many years and officially introduced us to Pierluigi.

How was this film born?

Each year Studiolabo invests some spare time (very little, thankfully!) in a cultural project. After getting in contact with Pierluigi we embarked on the journey of making the film that took us from childhood in Brianza to the true passion for design that defined his adulthood. We agreed that we had a moral obligation to introduce the world to Pierluigi Ghianda, a craftsman who has spent his life studying, manipulating, playing with one material—wood. A man of great charisma that has attracted the best Italian and international designers, becoming a designer himself, with an approach to work and life that today is obsolete but from which we can only learn.

Thanks to our dear friend Patrizio Saccò, a very good director of photography, we were able to experiment with the language of the documentary, which we felt was the best way to represent the world around the Ghianda workshop.

Is this the beginning of a project or a unique case?

We would like this to be just the beginning of a larger film project. The theme is that of manual labor, not seen with nostalgia but as the origin of design, a patrimony of knowledge to be disseminated. The craftsman does not know how to communicate what he does, he just does it. We would like to get immersed in the passions of these men and to create a dialogue around the aspects of production that often remain hidden in the substrate of the creative process. The next project, on which we are already working, will address the theme of the movable type printing today and its re-interpretations with digital.

Given your experience in the design field, what do you think is the role of artisans in the future of the industry?

Craftsmen as we know them are older people and probably their trades will end when they stop working. The craftsman is a man, a knowledge, a belief, a way of life. Is not transmissible to posterity as simple know-how, is deeply linked to the roots of the people and places.

Design, like any creative process, cannot exist without the production component. Also, industrial production cannot exist without the prototypes, the prototypes cannot exist without a hand that creates it, the hand cannot exist without the gesture. And that gesture is the craftsmanship—a gesture that is never equal to itself because it is always trying to improve. And this is the role of the artisan-craftsman, even though the model of the 1950s to 1970s cannot exist anymore. Today there is a new nebula of craftsmanship made of makers, self-producers and prosumers, which is struggling to gain consistency. It seems like if the need for craftsmanship is obvious but still not able to be channeled into something concrete or able to be reproduced. I hope for a future in which the craft will be knowledge and no longer a dumb know-how.

Contact Studiolabo directly to order the documentary. Images by Giancarlo Pradelli