Piloting a Super Aviator Personal Submersible

Our underwater flight training trip to Vancouver with Clerc Watches

by Steph Yin

Today—after a storied past involving crafts shaped like bells, powered by oars, equipped with flame-throwers, and designed after whale bodies—there’s a new sub in town, and it’s unlike any of its ancestors. Orcasub is a one-of-a-kind, personal luxury submersible—available to anyone who longs to freely roam thousands of feet under the ocean’s surface and can afford a $2 million-and-up price tag. Orcasub is sleeker than the average submarine—most other personal submersibles feature a giant bubble dome, which makes them hard to sink and steer (imagine trying to plunge a balloon into a pool). Orcasub, however, is built like a plane: complete with wings, directed thrusters, and two cockpits. With joystick piloting that would be second-nature to any gamer, the vessel is highly maneuverable. Flying in it feels weightless; more like slicing through air than water.

Cool Hunting traveled to Vancouver to visit where the Orcasub is produced and to test drive its immediate predecessor, a sub called Super Aviator that also sports an airplane design. There’s much in common between the two, more than just design elements, and our underwater adventure shed light on what to expect from the Orcasub. In its current iteration, modeled in the late 2000s, Super Aviator has been used for hundreds of dives, including expeditions with National Geographic and the Discovery Channel and offered an underwater flight experience unlike any other.

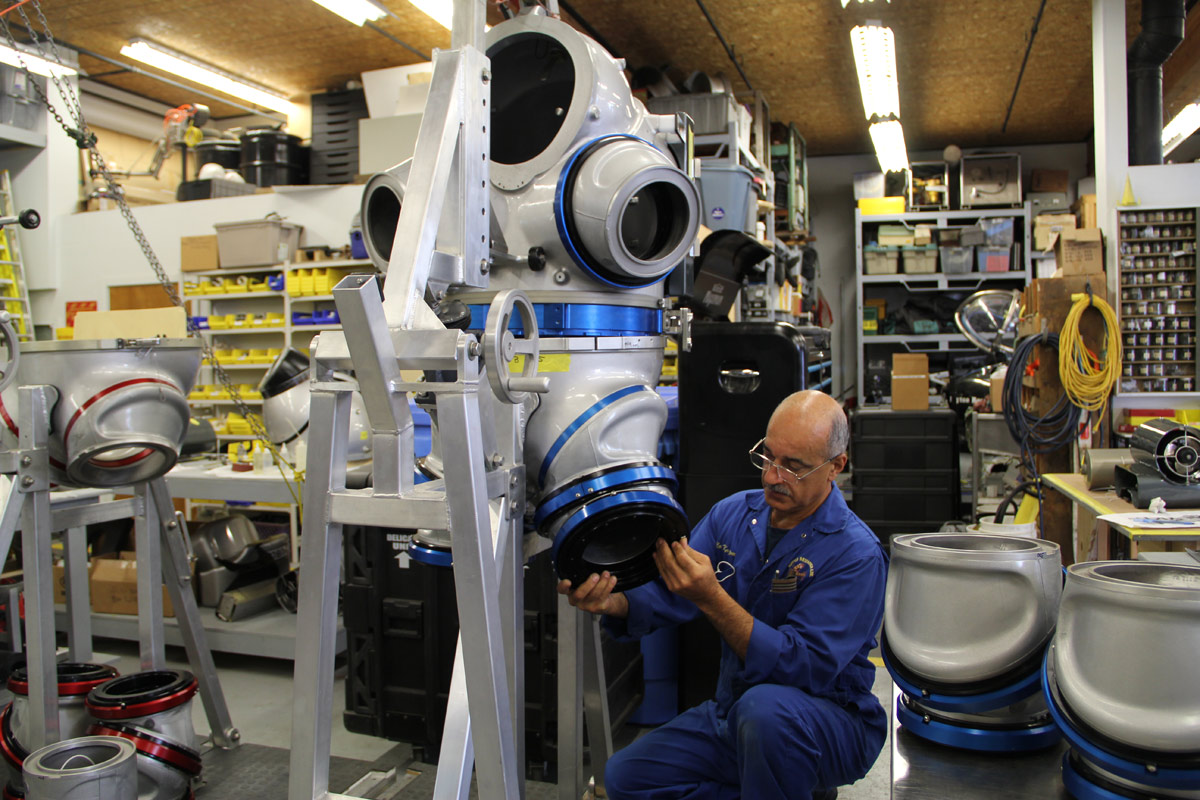

Vancouver is home to Nuytco Research, a pioneering manufacturer of undersea technologies, and one of three organizations collaborating to produce Orcasub. The other two are Sub Aviator Systems, founded by a team that helped build the original Super Aviator experimental model, and CLERC, a family-owned Swiss company that designs and manufactures powerful luxury diving watches. The unique, three-way partnership merges technological prowess, commitment to deep-sea exploration and conservation, and expert attention to craft.

Climbing into Orcasub feels like climbing into the seat of a serious roller coaster. A member of the flight crew makes sure you’re harnessed, then lowers a glass dome over your head. As the cockpit is vacuum-sealed around you, your ears pop slightly. The pressure in the cockpit will stay relatively constant for the rest of the trip, and even as you descend thousands of feet underwater, your ears won’t pop again. After a final sequence of adjusting air pressure and oxygen dials, it’s time to brace yourself for a ride.

A truck backs the submarine down a ramp and into the water. As the water level comes flush with your eyes, the urge to blink (and realizing you don’t have to) is strong. Your field of vision is half sky, half water, like a rippling Rothko painting. In the sky, mountains roll by. In the water, plankton swirl past.

Finally, it’s time to descend. Any claustrophobia in the cockpit gives way the minute the submarine is completely submerged. The glass of your dome has the same refractive index as water, so it disappears entirely once you’re immersed—so much so that fish sometimes bump into the glass. It looks, and feels, as if nothing is separating you from the sea.

Pushing the throttle, the sub will nose-dive. The deeper you go, the darker the water gets, transparent to aquamarine to light green to dark, dark green. Diving deeper and deeper, the water turns black—and then it turns pitch black. Somewhere in the blackness lurk orcas, from which Orcasub borrows its name.

With no visual reference, it’s hard to tell which way is up except by checking the gauges on the dashboard and the degree to which your body still feels like it’s falling. Climbing to visible waters, it’s fascinating to see all the different kinds of life as curious creatures swim up to investigate the sub.

The thrill of observing the ocean is matched by the thrill of flying the vessel itself. The joystick is sensitive to touch, but once you get the hang of using it in conjunction with the rudder foot pedals, piloting becomes intuitive. John Jo Lewis, one of the founders of Sub Aviator Systems, and an avid motorcyclist, calls the experience of piloting an “extension of one’s will” and compares it to driving a high-performance motorcycle. Unlike motorcycling, however, you have the added privilege of being able to experiment with acrobatics in the water, smoothly casting, yawing and drawing spirals.

Both Orcasub and Super Aviator are neutrally buoyant, meaning their pilots can pause and stay in one place to enjoy a deep-sea view. With both streamlined airplane designs and neutral buoyancy, OrcaSub and Super Aviator are able to provide unparalleled underwater experiences, combining the maneuverability and precision of a fighter jet with the stop-and-hover capabilities of bulkier subs. Orcasub, measuring 21′ in length, can travel at speeds of up to 10 knots or almost 12 miles per hour. Cruising at a steady speed of three knots, however, is ideal for observing sea life. The craft is electric, powered by rechargeable battery, so it’s non-polluting and quiet. With a battery life of over 72 hours on a single charge, the limiting factor for how long you stay underwater is how long you want to stay underwater. Prices range from $1.8 million for a craft that can go 1,000 feet underwater to $9.8 million for one that can descend to 6,000 feet.

Each member of the trifecta behind Orcasub brings a distinct profile of values and skills to the collaboration. The mission of Sub Aviator Systems is to promote ocean exploration and conservation. Lewis was a real estate entrepreneur before deciding to devote his career to deep-sea exploration. He dreams of Super Aviator as a vessel for intrepid citizen naturalists, pointing to Charles Darwin as inspiration.

Nuytco Resesarch was founded by Phil Nuytten, an inventor, entrepreneur, deep-sea explorer and member of the Métis, a Canadian indigenous group. As a teenager, Nuytten carved totem poles to make money, and became interested in the ocean after receiving a commission to make a totem pole with sea creatures on it. He started diving, building his own breathing apparatus from scratch and opening a dive shop at just 13 years old.

For decades, Nuytco has designed pioneering diving suits, submersibles, rovers, and other deep-sea technologies, including ones that have been used by NASA, Jean Michel Cousteau (Jacques Cousteau’s son) and filmmaker James Cameron. The company brings certified, patented components to Orcasub, which makes the sub eligible for insurance coverage and ensures standardized manufacturing of parts.

CLERC, which has a 140-year tradition of making handcrafted watches, brings luxury to the Orcasub experience. They advise on interior finishing, customization, and creature comforts, elevating Orcasub as a piece of art and craftsmanship. Furthermore, with Orcasub, CLERC gains access to the most exclusive underwater laboratory in the world. Starting with their 2015 Hydroscaph GMT model, CLERC will affix their luxury diving watches, which they call “exploration machines,” to Orcasub vessels to test the watches under conditions of extreme speeds and depths.

Despite their differences, all three parties involved in the making of Orcasub are enchanted by the ocean—and curious about how much of it remains unexplored. They put deep-sea exploration on the same plane of urgency and importance as space exploration, comparing their efforts to that of SpaceX. Nuytten, who has already crafted plans for future underwater civilization, is fond of pointing out that all of Earth’s life exists in just about a dozen miles—from the deepest parts of the ocean to the tallest mountain peaks in the sky. He believes it’s human nature to wonder at everything that exists in those dozen miles—to push the bounds of our experience. Orcasub is a vessel to help us do so.

Orcasub and Hydroscaph images courtesy of Clerc, all other images by Steph Yin