Studio Visit: Lex Pott

The Dutch designer on using extensive research and experimentation to create a new language from archetypical materials

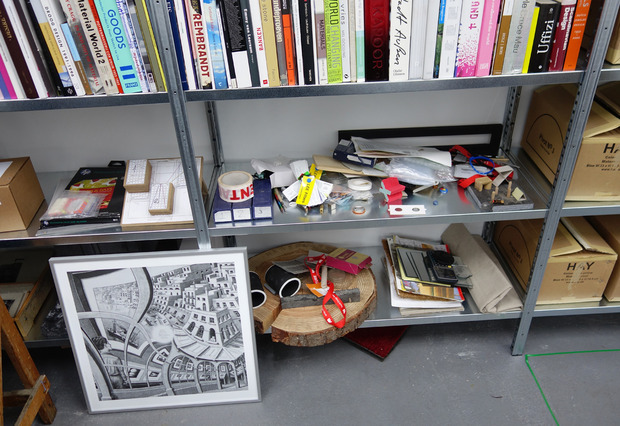

Since graduating cum laude in 2009 from the prestigious Design Academy Eindhoven, young Dutch designer Lex Pott has been very busy—first with working for Hella Jongerius and Scholten & Baijings, and then with starting up his own studio. When we stopped by his Amsterdam studio recently (which he had just moved into), Pott was working on a patina concept for Volvo and about “20 other projects”—but he still took time out to discuss his methods and interests with us. Talking with Pott is easy, but so is appreciating his work.

How do you manage it all? Do you work weekends?

Actually I quit working weekends because I did my internship with Hella Jongerius, and the first thing I noticed is that they work from 9:30-5:30. In that time they are really efficient and productive, but if you do too much overtime and over hours, you’re not productive anymore. You can work forever, because you’ve never finished all the work so you can always continue. But I just say “no let’s wait until Monday and start again.” The first three years I did seven days a week, of course yeah. You want to generate something. But now I try to keep the weekends free. My girlfriend was also getting more and more pissed. [laughs]

Do you find that you’ll end up figuring something out in a self-initiated project that then goes into a commercial project or vice-versa?

Yeah, that’s why I really like sort of a hands-on approach in making stuff and understanding what a material does and how it works. And all of the ideas come from the previous projects, or a weird experiment that failed. So I think it’s really important to work physically and sometimes for producers I need technical drawings, but I’m horrible with computers—I only know how to open my email and look at blogs—so I hire people to do the technical stuff. The funny thing is, in technical things you never solve something. You always have to see it in reality to understand if it really works. Most of the things that are being designed in the computer, you also see that they’re being designed in the computer. It’s not my cup of tea.

How do you feel about being part of “Dutch Design”?

I think the big movements are now in London and Scandinavia. I think [with] Scandinavian design—the big brands, they are doing really well. If you study in Eindhoven there are people from Sweden, from Asia, the UK. So it’s more the mentality that fits with you as a designer, and if you fit the mentality then you become a nationality in a way, so you’re a Dutch or Scandinavian designer. But that’s also the funny thing with Scandinavian design; I do work for Hay now, and that’s Scandinavian, but they also work with Dutch designers. I think for the design fields, the Netherlands is too small. Everyone talks about Dutch design, but in the Netherlands, no one talks about Dutch design. So it’s really an export product that we have, and therefore all of the designers work abroad and sell abroad. Here there isn’t a lot of demand for what we do, it’s really a niche world.

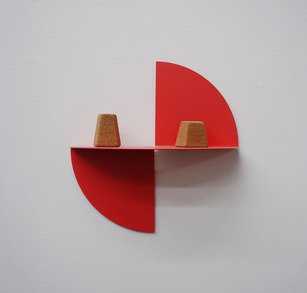

Speaking of, what are you working on with Hay?

I did some wall shelves and some wall hooks. That’s what’s coming out soon. And behind the scenes, I’m working on developing a scissor with them. More wall shelves, maybe some mirrors. Colored mirrors, colored marble, and the scissors made out of steel or different metals in different colors. It’s mostly accessories that I do for them, it’s also an easy scale to work on and develop, but hopefully in the future I can do furniture pieces and bigger pieces as well.

You do furniture?

Actually not so much, I do mostly accessories. But in my free work I do a lot of furniture. But they’re really expensive and difficult pieces to make. But now I got the assignment from a few companies that develop furniture, shelves, tables, chairs—so I will work on that from now through the upcoming year. That’s also a crazy thing, I find it impossible to work from a briefing. I really need to study myself and think “okay, this fits with this company.” So therefore it maybe takes a bit more time but it’s also a bit more authentic, because you do it from a personal necessity instead of a public necessity. But Hay was really a dream coming true. I also have Vitra on my list, but it takes forever—if you’re lucky enough to become part of it—because they only work with established designers. It’s almost impossible, they are really selective. In second place I had Hay because it’s a new generation brand, it’s really growing, expanding.

It will be great for me as such a young designer to already be part of a nice company like Hay.

Did they dictate the objects? How does that work?

Yeah, it started in Milan. I presented something. But I had worked for Scholten & Baijings for three years—first my internship and then I started working there—and so I had already met the people from Hay, but as the intern idiot in the back working on a model [laughs]. But in Milan we started talking and the good thing is, they said “That on the wall, we want it. Can you take it off the wall and ship it to Copenhagen? Then you don’t have to present it anymore in Milan because you already found a producer.” I thought, “okay, they take it off the wall, they develop it, and in three months it’s in the shop.” But it takes almost one and a half to two years from the first prototype to the shop with a barcode. It will be great for me as such a young designer to already be part of a nice company like Hay.

Was it scary to start your own studio?

Oh yeah! Because you get out of the comfort zone—[when you work for a company] you have an income, no worries, no stress, you just go to work and do your job and go home. If you start for yourself you have nothing and you have to work your ass off and it’s not secure, but looking back I really don’t regret it. It’s only getting better and better! But it was really a difficult and tough decision. I wanted to do my own stuff, and when you design for someone else you make A, B, C proposals, and I say I like C, and they go for A. And then you have to execute A and work on it for a month. When you work for yourself you say, “this is what we’re going to do and that’s the way it’s going to happen.” So it feels much more rich and much more free. I think you work more, independently, but it’s much more satisfying because you do it for your own name and for your own portfolio.

At school, how did you keep your work unique while working within a group of students?

At Eindhoven they are really good in making every designer as an individual designer, so they look at the method of working and the type of work you make. The education is really personal. I have a lot of friends from the academy and we all went in a totally different, strange direction, but we had exactly the same courses. So I think Eindhoven really trains you to be authentic in a way, and to think on an independent level. With a lot of the industrial design studies you’ll see that it’s all more similar—they all design phones or vacuum cleaners, the electronics. It’s also probably something that comes from yourself. It’s really difficult to describe the creative process, you have personal fascinations and you dive into something. It’s also a matter of good Googling, because sometimes I have an idea and if I Google for a half an hour, I know if it exists or not. Then you can decide to continue or not.

Your work has the magic of feeling really sensical but super new at the same time.

There’s a lot of insecurity. A lot of the projects that I did, my girlfriend almost made the decision. The metal plates with the chemical formulas, that was the start of a whole big project. But when I had these first samples I said, “Oh I’m not going to exhibit this, I’m a product designer and they’re all going to think I’m crazy to put something on the wall as an art piece. I’m not an artist.” She said “No, you should hang it on the wall!” I said no, but then it was at a small exhibition in Eindhoven that I presented it to test the people. That’s really the scariest moment, when you present something for the first time, you’re so vulnerable. After a week I had sold four sets or something, so I thought, “Okay, must be something.” Then after awhile I realized that people also appreciate this different approach, and sticking to the plan in a way.

This is similar to the briefings. For me it’s impossible to design something from a demand. I always have to formulate my own project and my own ideas and study on it. Maybe it’s not productive at all, because you need more time to experiment, but in the long term the outcome is—for me—more interesting.

Is it materials that mostly drive you?

Materials, processes and also qualities of materials. I work mostly in wood, stone and metal, which are super normal, cliche categories. When I zoom in and I study on it and experiment with it, I always find a nice hidden quality or something that is not being designed before. With the patina project, it’s everywhere—in churches, next to the road—but it’s not being designed from a designer’s point of view. It’s just a reality and a quality of the material. If you put it in a design context, all of the sudden it becomes a new story or a new translation. That’s what really fascinates me.

You’ve stated that you work intuitively, is that what you mean?

It’s a lot of studying, but choosing the materials and the subject is intuitive. It’s the same thing with trends, for instance. You can only define a trend in the beginning by being intuitive. Five years ago I thought, “okay copper, brass, steel, aluminum are nice to work with” and all of the sudden you see designers around the world also popping up at the same moment with the same material and the same qualities. And then it becomes like a moment in time where it becomes a trend. In that sense it’s also frustrating because after a trend is over it’s not interesting anymore, or it has less commercial value. So it’s also a little risky to work intuitively, because you can also choose a wrong direction.

It’s also daring to stick out your neck.

It’s also daring to stick out your neck. That’s one thing I really appreciate and admire from The Design Academy—you have this chairwoman, Lidewij Edelkoort, she’s really amazing. She goes through the graduation show, and sees a fucked up, weird, strange project and she goes “this is good, this is what we’re going to show to the world.” And then she puts a lot of promotion behind it, and she’s taking the blame if no one likes it. But she’s also taking the credit if it becomes the new big thing. So she’s always really one or two steps ahead, and most of the blogs—there are a lot of exceptions—are reviewing trends of the moment, maybe they want to please the mainstream and show what they want to see.

So what do you think is next?

Oh that’s difficult. I still believe in all of the natural materials, the simple, archetype materials that also have a huge historical value and have been used for thousands of years, but nowadays you can place in a new context because of new technologies and qualities.

Like with your wood Diptych project?

Yeah, sandblasting. The process and the materials were already there, but if you combine both it becomes a new image or a new language in a way. That’s what I really believe in. For me, I think that I’m a really bad designer. I can’t draw, I can’t make any sketches, I’m really bad at making shapes. But I sort of hide behind the material experiments and studying. So in that sense, if I design something without a concept or without an idea, I would fail totally. That’s also my insecurity; I know I’m not a good, “typical” designer, so I have to invest more in research and development and experiments. All my work is quite rectangular, geometric, easy, simple in a way. I can’t do anything else! [laughs] I just want to tell stories through shapes or an object.

How did you get into design then?

My parents are artists, my father is a painter and my mother was a sculptor. It’s super hard to survive and make a living out of it, and I saw this whole life of struggling. I thought “I really appreciate this artistic value but I also want to give it sort of a necessity.” Therefore I chose Eindhoven, because they are on one hand really artistic, and on the other hand it’s also applied arts. That was my theory before starting, and somehow it worked out. I can make a living out of it, people use it, and I also have the freedom to make more artist work or sculptural work. So the decision of becoming a designer really came from my parents, or it was a reaction.

If you hadn’t gone into design, what would you have done?

Actually I was choosing between becoming a yacht broker—selling yachts in a suit in the south of France somewhere—or, when I was young I wanted to become a diver.

Those are both to do with water. Do you like the sea or does that play into your work?

More of a hobby. When I was young I had little boats. I had this newspaper side job and I saved all my money to buy a small boat and to be on the water. I did a lot of fishing as well, also on the sea. That’s where it came from but I can’t really translate it or see a link into my work, it’s more of a hobby. But when I’m on holiday, I always rent a boat.

Photos by Karen Day