Interview: Eat Offbeat Founder, Manal Kahi

With a new cookbook and a reimagined approach to catering, this profit-with-purpose company continues breaking down borders

In 2013—during the conflict that displaced millions of Syrian people, around a million of whom sought refuge in Lebanon—Manal Kahi left Beirut for NYC to attend graduate school. She planned to work in multilateral or environmental affairs, but her concern about the crisis back home and her dissatisfaction with grocery store hummus (clearly two very different issues) started her on a different journey. “You can only imagine the amount of discrimination that was ensuing,” Kahi tells us about the influx of refugees in her homeland. “And I had left, with a little bit of guilt in the back of my mind about not being able to do anything. But there it was,” she says, “when I started thinking.”

Her own homemade hummus, made using her Syrian grandmother’s recipe, had been a hit with friends, and she thought about how many magnificent family recipes were being cooked all over the city. With that, the concept for Eat Offbeat was born.

Located in Long Island City, and initially launching as a catering company, Eat Offbeat works with the New York branch of the International Rescue Committee—a non-profit, non-governmental organization—to create opportunities for refugees and asylees. But Eat Offbeat isn’t a charity; it’s for-profit, and the chefs—from Iraq to Senegal, Sri Lanka and Venezuela—are employees. (Each staff member, already a talented home cook, receives on-the-job training that includes everything from navigating an industrial kitchen to specific New York laws around food preparation.) Eat Offbeat proves itself to be profit-with-purpose, and as Kahi explains, “You can be profitable and successful, and also be impactful on a social or environmental level.”

The company hinges on three foundations: “The first is to create quality jobs for talented refugees who want to be in the food industry. The second is to build community and build bridges between us cooking in the kitchen, and our customers having our food at home or at the office,” Kahi explains. “And the third goal for us, ultimately, is about changing the narrative around refugees by showcasing a different and a more positive story.”

That narrative centers on refugees, asylees and immigrants adding value to the cities, communities, culinary scenes and the economy—rather than the misguided, one-dimensional trope that immigrants and refugees drain government resources. “This is a very important thing for us to showcase,” Kahi says. “There’s some sort of a narrative where it’s always—whenever you think of refugees, it’s always sad stories. And, it’s true, I’m not trying to deny the fact that there is a lot of suffering that happens. But there are also cases where there are a lot of success stories, especially here in the US. We talk a lot about the American dream, we talk a lot about people rebuilding their lives, and that happens a lot in the US or abroad with refugees who come in, start their own businesses, make changes around them, and basically end up making their communities better and stronger.”

This is true of Eat Offbeat’s team in New York. “It’s a story where refugees are the chefs, and they are the heroes,” she says. “They are the ones helping New Yorkers discover something new and something different, not the other way around.”

Kahi says beyond creating jobs and sharing food, she hopes Eat Offbeat inspires others to be more thoughtful with their own business models. “The dream is to inspire more and more businesses to try to find a viable model that’s also impactful—or the where impact is kind of embedded. We’re lucky in a sense, because impact is really embedded. We like to say it’s baked in our DNA,” she says. “This is a very viable model. Every business should start having a socially minded component rather than the other way around. We shouldn’t be the special model out there, it should become common practice.”

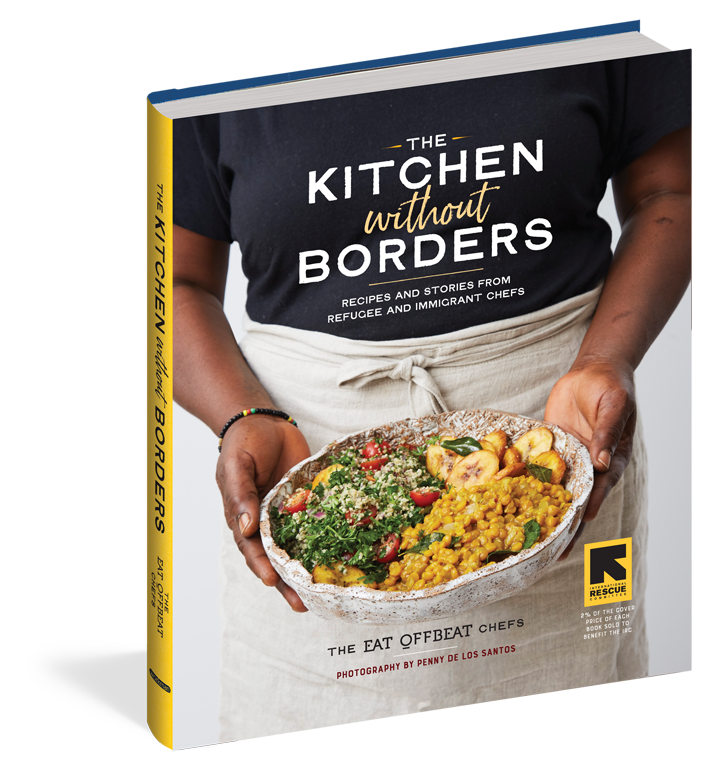

The pandemic forced Kahi and her team to rethink, reimagine and relaunch. Almost overnight in March last year, they lost 100% of their business as a catering company. “It’s been a really rough year for us,” she says. The team began creating meal kits (available in NYC) and provision gift boxes (available nationwide), and have just launched their first cookbook: The Kitchen Without Borders.

The book was always going to combine recipes with stories, as is the fabric of Eat Offbeat itself. Each recipe comprises much more than a list of ingredients and a method—each dish is imbued with tales of memories, places, family and identity.

The book was always going to combine recipes with stories, as is the fabric of Eat Offbeat itself. Each recipe comprises much more than a list of ingredients and a method—each dish is imbued with tales of memories, places, family and identity.

“When you serve any dish for someone, to know a story around that dish, all of a sudden, it kind of magically becomes much tastier,” Kahi says. “Tasty to begin with, but then you know something about it and you just start tasting things a bit differently—the flavors come out, maybe differently or they go to different parts of your brain, and they kind of trigger different emotions.”

Ultimately, the intention for the book encompasses Eat Offbeat’s central mission too: that readers discover different narratives and different flavors, creating new perspectives and breaking down boundaries. “Now I get to try food from Iran, now I get to try food from Senegal and see all of this richness of flavors,” she says of the reader experience. “And now we’re gonna get to try chef Shanthini’s food from Sri Lanka.” Kahi wants people to come away thinking, “I am lucky that these people have chosen to come and live with me here.”