Sequence Jewelry

Salvadoran-born New Yorker Ariela Suster enlists gang members back home to produce her line

by Laila Gohar

Salvadoran-born Ariela Suster dropped out of Harvard and moved to New York City to pursue a career in fashion. After a string of editorial positions at various fashion magazines, she followed her true calling to create a brand that gives back to communities in El Salvador. Five years and a chance meeting later she launched Sequence jewelry. The accessories line employs ex-gang members and at-risk youth from Tepecoyo, a town ridden with gang violence in southwestern El Salvador to dye and knot the bright, bold jewelry she designs. We sat down with Suster to talk about her journey from El Salvador to New York and back, and how Sequence came to life.

Give us the backstory, how did you launch Sequence?

My purpose was never to launch a product, it was more about creating something bigger than myself that makes a difference in people’s lives but is also aesthetic. I had sketched jewelry with traditional Salvadoran designs—mostly necklaces and bracelets —but using totally different colors and materials. I was living in New York but went back to El Salvador, my home, to try to find a group of people that I can work with on the sketches. I was looking for local artisans who could transform my sketches into jewelry. After a year I met Oscar, the person who I started Sequence with, on the street. I believe that our meeting was meant to be. From there, Sequence was born.

What came next?

Oscar was selling handmade jewelry on the street to get himself through school. I liked his work so I gave him my designs and the materials I wanted to use which were nylon ropes that are traditionally used for hammocks, fishing nets, and furniture. He was a bit reluctant at first because he had never worked with those materials but when I saw what he created I was in awe. It was exactly how I had envisioned.

I brought the jewelry back to the US and started selling it online and at a couple of different stores. Soon, I sold out and needed larger quantities—and therefore more hands—so Oscar recruited his friends from the community to work with us at the small workshop we had set up. The community where the workshop is located is ridden with gang violence. Many of the twenty-five people that are now employed by Sequence either used to belong to a gang or were at risk of being recruited by a gang and instead saw this as an alternative opportunity—the only opportunity really—to make a decent living. Instead of being recruited by gangs, we recruited them for the workshop to make jewelry.

What about the aesthetic of jewelry?

Traditionally Salvadoran jewelry is made with muted tones—a lot of brown, burgundy and black. To me those tones reflect the violence and the harshness of life and in a way, the pain. I wanted to create jewelry that was symbolic of hope and a bright future so I opted for bright colors. It is very important to me that the artisans work with colors that are lighter in the hopes of lifting their spirit in one way or another.

We started off with a few small clutches, bracelets and necklaces. Now we’ve expanded to include more designs. The design process is really collaborative. I draw the design and the team at the workshop gives me their input and ideas.

What is the story behind the name, “Sequence”?

I’ve always reflected on the sequence of events that allowed me to do embark on this journey. From leaving Harvard, to my jobs in fashion, to randomly meeting Oscar. At the end it all made sense. From a sequence of events the line was born. Also when I was observing the artisans weaving the threads on the looms or dying the fabrics there was always a sequence, a series of steps.

There seems to be a lot of duality within the collection.

Yes, I’m fascinated by the duality of life and the two sides that exist to every story. My entire life exists in duality: I move back and forth between New York and El Salvador. I studied dance and psychology, so there’s the duality of the body and mind. I wanted to create something fashion oriented but with a cause. Then there’s the duality of the color—the bright versus the dark and what that means. For me, duality and contradiction are what keep life exciting.

What’s next for Sequence?

We are starting a program from the workshop that provide participants with practical experience free of charge in collaborating with an organization called Glasswing, which builds healthcare and education programs in communities across Latin America. The artisans as well as people from the community are invited to join and take the classes offered for free.

We also currently have a workshop for children on the weekends where they can come in and participate in various art and music activities. It gives them a place to go. Children as young as 12 get recruited by gangs, so by providing a safe haven we hope to reduce the likelihood of that happening. We are working on extending that program to every day after school.

As for the jewelry itself, it’s more designs, more colors and collections, and through that, more opportunities for employment, which could result in a rebirth for a community that is so haunted by gang violence.

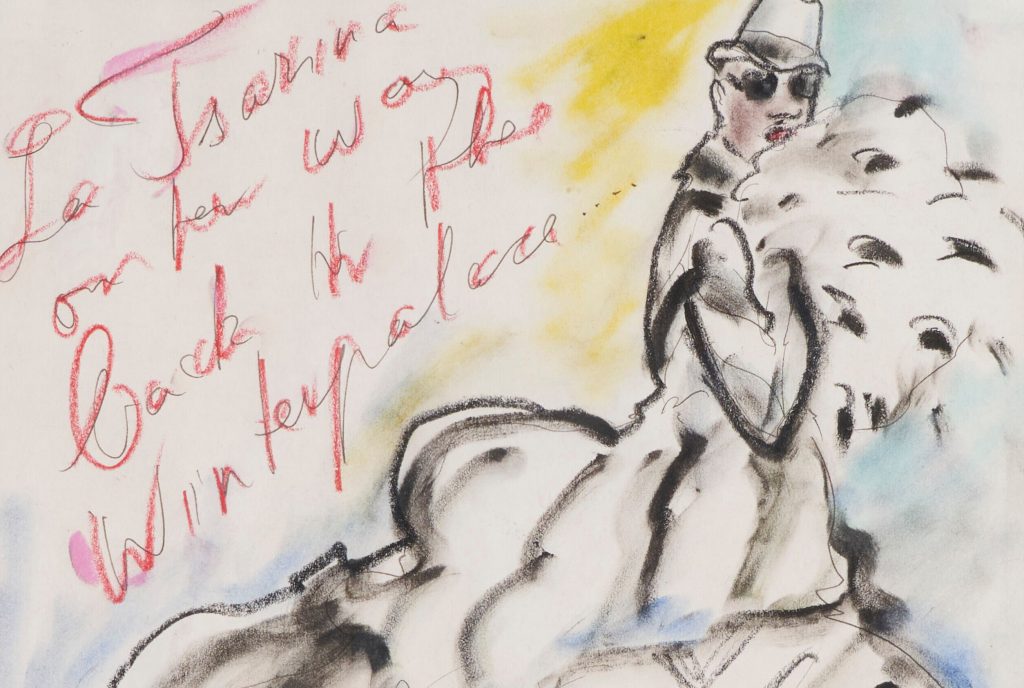

For more information on Sequence visit their website. Images courtesy of Ariela Suster for Sequence.