Interview: Nature-Activism Photographer Daniel Beltrá and the New MacBook Pro

From insight on editing in the field to the color palatte of our environment

Apple recently released an updated MacBook Pro with significant performance improvements that were welcomed by demanding pro users. The new MacBook Pro features a quieter keyboard, faster processors, more memory and for the first on a Mac—a True Tone display. True Tone has existed on the iPad and iPhone for generations, but the technology—which matches the whitepoint on your screen to the ambient light tone around you—is new to a computer display. The technology makes viewing the screen like looking at a white sheet of paper that reflects the light around it. The difference is in the variability; other screens show white at a set value regardless of the environment you’re in—ultimately increasing eye strain. The feature is a vital addition to mobile interfaces, where eyes are inches from them and little technical editing is done. But, as the feature stretches to larger screens (like those designed for more intimate editing and visual work) the question arises of whether or not this is good or bad for photographers, and other artists, who deal with color representation.

Plainly put, no. The eye bypasses the difference in the white on the screen and the ambient white around you and perceives the colors, as you see them, as accurately as possible. Therefore, regardless of the lighting in the space where you’re editing, the resulting image is going to look right in any environment. The potential changes are reflected on all tethered displays, even to the touch bar. And, it does all of this based off the directions of a dedicated ambient light sensor near the screen’s camera.

This innovation lets the user, or editor, have the most natural viewing experience. Previously, white levels were predetermined with a working environment in mind—including its ambient light—and programmers understood its influence. Our brains worked similarly; they made sense of the color based on a mix of prior knowledge and our current environment. But now, the color seen is the truest rendering of that color–taking into account all perspectives. The biggest hurdle for many creatives is knowing that the white value of their screen is shifting and accepting that it’s relative to their working environment and not impactful on the end result.

Photographers who shoot and work in environments beyond studio walls and plain-colored backdrops may be impacted most. The ambient light around them could, potentially, never be consistent.

Photographer and activist Daniel Beltrá currently makes work focused on human impact on the environment. Shooting in the field, Beltrá sometimes makes edits there, but oftentimes returns to a vastly different light space to do so. His work, which has been exhibited around the world and encapsulated into numerous award-winning collections, is often edited for print and exhibition audiences.

We spoke with Beltrá about his journey, process, editing on the MacBook Pro with True Tone, and some of his most moving projects.

You’re both a photographer and an environmentalist. Did one come before the other?

It all started when I was a kid. Nature was a passion and photography also a big hobby. But, they were traveling parallel; they were not intersecting for a long time. I tried very early on to do some nature photography and photographing birds and especially big, big birds. And it’s not very easy when you’re a kid without much gear, and I kind of gave up on that.

When I was studying biology at the University of Madrid I landed a staff job as a photographer for the EFE, the Spanish national agency. I thought, at some point, what if I manage to put those two things that I’m interested in together? And then little by little that’s where the career started in this world. It was only years later that I quit my job and started to do work with Greenpeace, the environmental group.

How has your work evolved to the focus it has today?

I think that my love for nature turned into a concern pretty rapidly. At some point I also started to feel there were too many photographers showing us how beautiful the world is—and I felt that was very important. But also it was perpetuating a bit of a myth—when you see beautiful animals in the wild landscapes—I felt that’s not the reality unfortunately.

It’s a fairytale really, how gorgeous the world is, and it is, but really what’s happening is we’re trashing it, either directly or indirectly. That led me to thinking, what can I do with my work? And through that first year of more than three-decade long relationship [with Greenpeace], I worked all over the world doing jobs for them, and it opened my eyes to many issues.

Which body of work so far has moved you the most?

I would think the work I’ve done around tropical forests because I’ve worked a lot on this subject, mostly in the Amazon. I’ve been going there almost every year for a decade and a half. It’s a project that chose me, and I think it’s so important to try and stop its destruction and degradation. And, I know aesthetically it may not be the most interesting.

But the point of your work isn’t purely aesthetic, right? And looking at that section of your portfolio, there’s still some really beautiful images, but as you look at the body of work, it’s easy to understand the magnitude of the issue.

And that’s really what motivates me. Of course, it’s very flattering and very nice to have a show in an art gallery or museum. People say how gorgeous the images are, but I’m not doing the work for that. I’m trying to denounce what is happening.

Do you edit images in the field or in the studio? Why?

It’s a mix because normally I need some photos when I’m in the field depending on the project. What I do every day, regardless, is back up everything. If I have time in the field, I catalog. Though I will not get to the point of finalizing [for print] in the field.

You’re using the new MacBook Pro with True Tone display. Does a shifting visualization of “white” help your work?

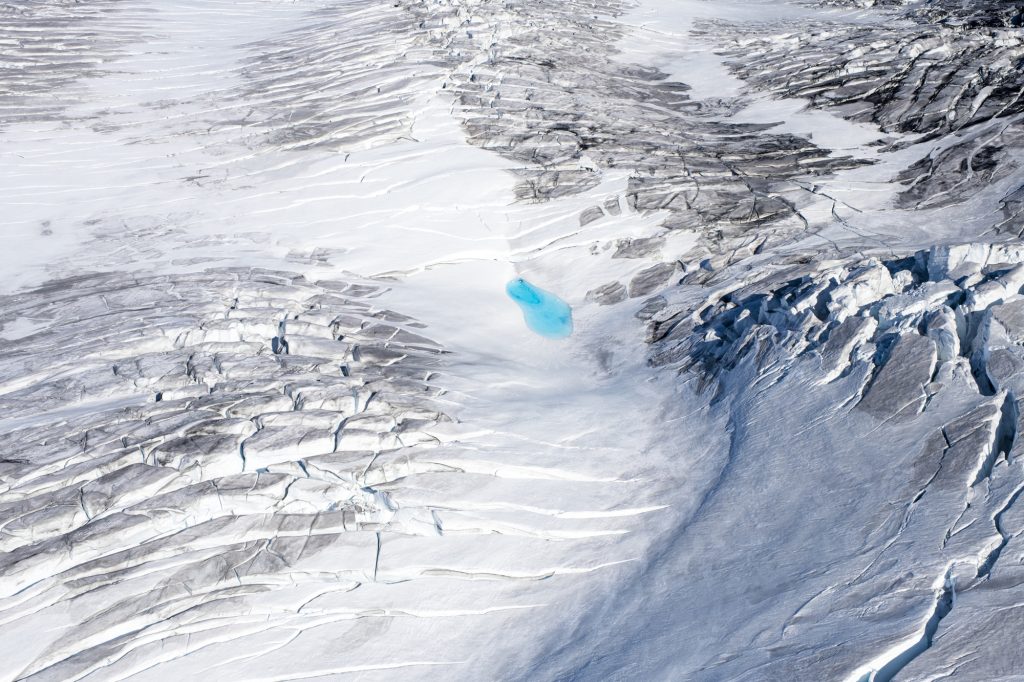

I’ve definitely had many questions because when we’ve been doing things for a certain way for a long time, it’s a bit difficult adjusting. An assignment in the field will be the main test for me—but for now, if I go next to a window or a lamp, I like what it does; if anything, I thought maybe, sometimes, the correction is a tiny touch too warm—especially when we’re looking at photos with ice or snow. What I think will be very interesting is using True Tone in a tent—when I am in the field under a yellow or red or green tent the dominant color is so strong that it’s really difficult to see colors well. I will do that [when in the field next], and it will give a very good idea of the response.

All images by Daniel Beltrá, courtesy of Catherine Edelman gallery

What are your thoughts?