The Office For Creative Research

The creative trio uses boundary-defying interfaces at the nexus of art and technology to help people understand big data

NYC-based The Office for Creative Research unites three internationally renowned media artists—Jer Thorp, Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen—in an exploration of data’s expressive possibilities. OCR harnesses vast troves of raw data, streaming it through boundary-defying interfaces that change how we interact with information while enabling us to make sense of the world in new ways. “We make data accessible,” says Rubin, who refers to his co-founders as “wizardly” coders and “great educators.” All three have held prestigious appointments at the university level, and were drawn to working together by their mutual admiration of each other’s work, which falls at the nexus of art, design and technology. Rubin elegantly summarizes their collective foundation in explaining that they’re “fundamentally artists, but artists who have extensive and rigorous technical training and understanding.”

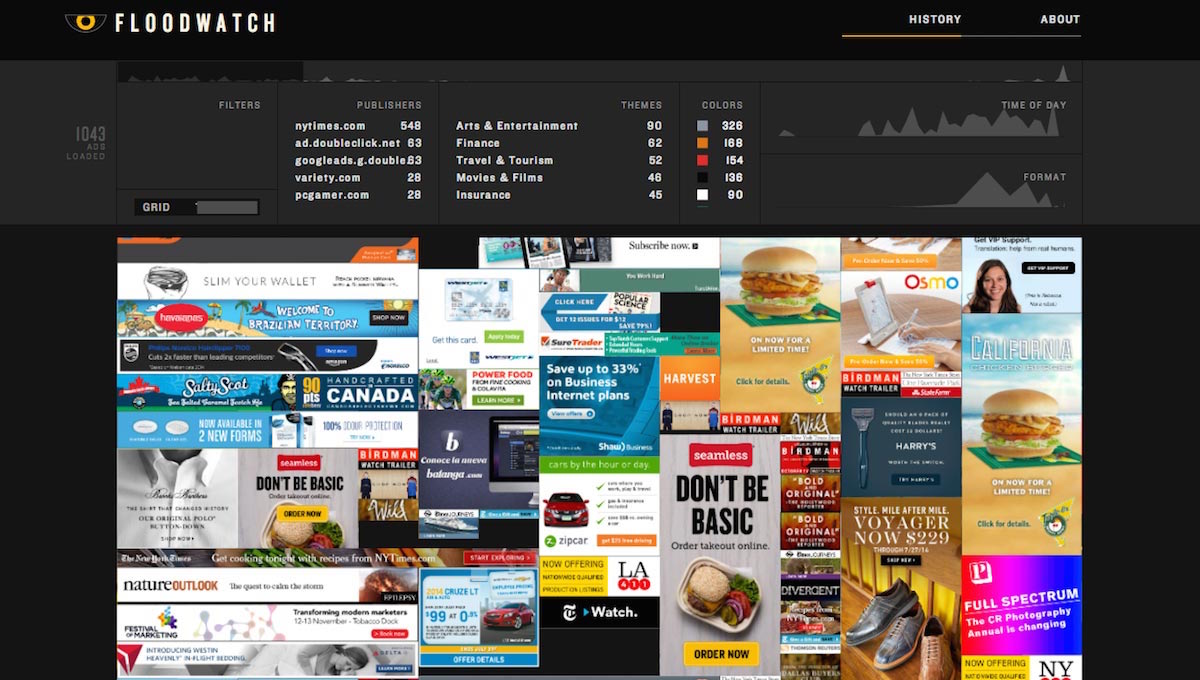

For example, Floodwatch exemplifies OCR’s ability to simplify complex issues in information management. The free Chrome browser extension empowers consumers by making it possible to surmise the profile that advertisers have generated for them. Our virtual lives are papered with ads that subsist just below our level of consciousness, and Floodwatch contextualizes those into a “billboard” tiled with each of the ads we’re served throughout our browsing history. Underwritten by a Ford Foundation grant, Floodwatch was conceived with the recognition that individuals didn’t have tools to understand how their data was being used by advertisers, or the impact that this profiling has on their privacy.

As Thorp points out, we all have an online “second self”—meaning, there is what we choose to display by sharing the books we read and vacation photos posted, but there is also another, unconscious profile that advertisers create from our online meanderings, web searches, purchasing behavior and even from the wireless networks to which our mobile devices connect while visiting retailers in the physical world. To illustrate how far from reality this “second self” can be, Thorp opened his advertising history to interpretation. Those surveyed concluded he is a single Jewish gamer in his 20s—none of which is accurate.

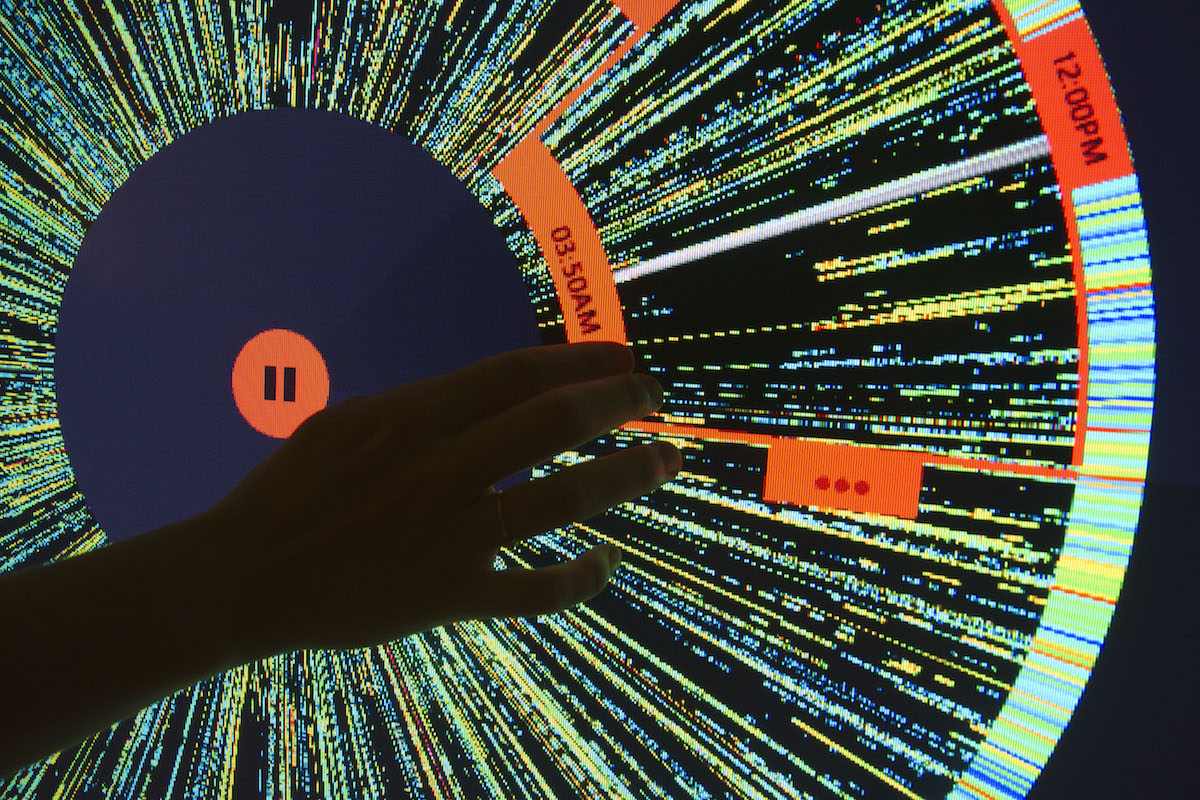

Data teams at the companies OCR works with are often surprised to hear the group introduced as “artists.” Says Thorp, “Artists have to be very good with the tools we use, with the mediums we engage with… We have to be exacting, detailed in research, preparation and construction—and we bring those things to this type of work. We try to bring abstract thinking, too, but we don’t always operate in the abstract.” It is as recognized creators in art, storytelling and media that the members of the OCR earn their engagements. Thorp was the Data Artist at the New York Times R&D Lab from 2010 to 2012, an opportunity that came about through a connection with Hansen, a longtime Times researcher and current Director of Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation. “It is an amazing beast,” Thorp says of the lab. In 2011 the R&D Lab built Cascade, a visualization tool that displays how data propagates through social media and illustrates the NYT’s central role in how stories become viral. As for why extreme innovation exists within so-called old media, Rubin suggests: “A more mature company views it as critical to think freely, and to continue to reinvent their role.”

History, experience and maturity are assets to the forward-thinking approach of another OCR client, Microsoft Research. OCR is engaged with the Digital Crimes Unit, the division charged with shuttering malicious botnets, the software networks that infect machines for nefarious purposes. The largest botnets have hundreds of millions of computers attached to them, and the trails they leave behind create a dataset almost too massive to apprehend. As a result the OCR has created Specimen Box, a new modality to experience this information as an auditory interface designed to prompt technicians to isolate and explore what breaks the pattern in a spread of data, so as to learn more about how they might stop these botnets. Thorp, who speaks reverentially of the talent assembled at Microsoft, appreciates their understanding that research is an investment, “not a quick money play.”

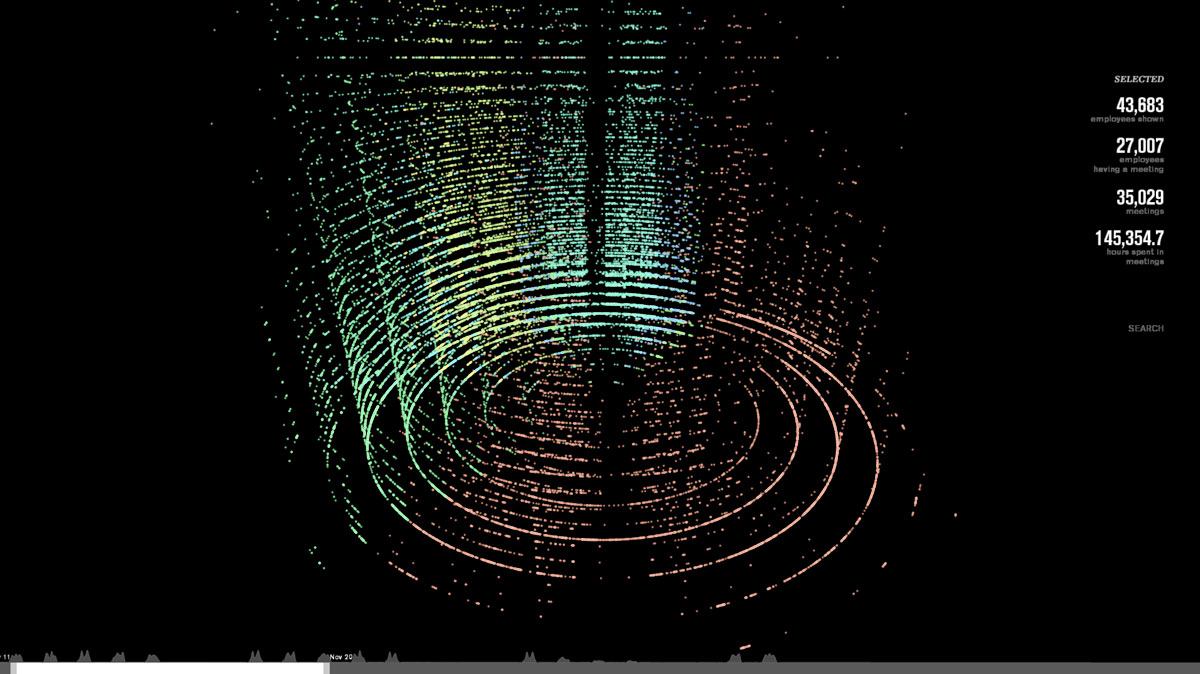

OCR has also worked with Microsoft’s Envisioning Group, using one of the company’s more familiar products, Outlook. Using data collected from Outlook, OCR created Convene, a tool that enables the visualization of meeting activity across a large organization. If, as Thorp suggests, the pulse of an organization is contained within its calendar and email data files, then Convene will create the opportunity to find new vital signs. Convene mines the work calendars and meeting room schedules of Redmond’s 100,000 employees and contractors to help them understand more about the social networks within companies, and to help them work more efficiently. These two Microsoft projects exemplify what OCR does best. The group creates beautiful visualizations to render complicated networks with greater transparency. These tools aim to shatter the boundary between analytics and communication, providing a visually lucid way for a business to tell its story. Built at the limit of today’s technology, they also present a sketch of where our interfaces may evolve in three to five years.

We’re more interested in building instruments for asking better questions.

In some ways OCR is similar to other companies working in the big data and data visualization space—they design algorithms, build databases and construct visualizations. There is, however, an important distinction that the OCR likes to make, calling their work “question-farming tools.” Says Thorp, “People always want answers, but if you don’t know the right questions to ask, those answers aren’t going to be very useful. We’re more interested in building instruments for asking better questions. That is the case in the artwork we build as well. It’s pedagogical and open-ended, it’s about giving people a framework to think differently about something, not about telling them what to think.” Rubin emphasizes that the group’s native approach is an artistic one, adding, “We’ve all been working in the discipline of art, and art is not about answering questions as much as it about provoking a different point of view, or provoking someone to see something differently than they saw it before. So when we look at data, we’re trying to find ways to help people formulate new questions.”

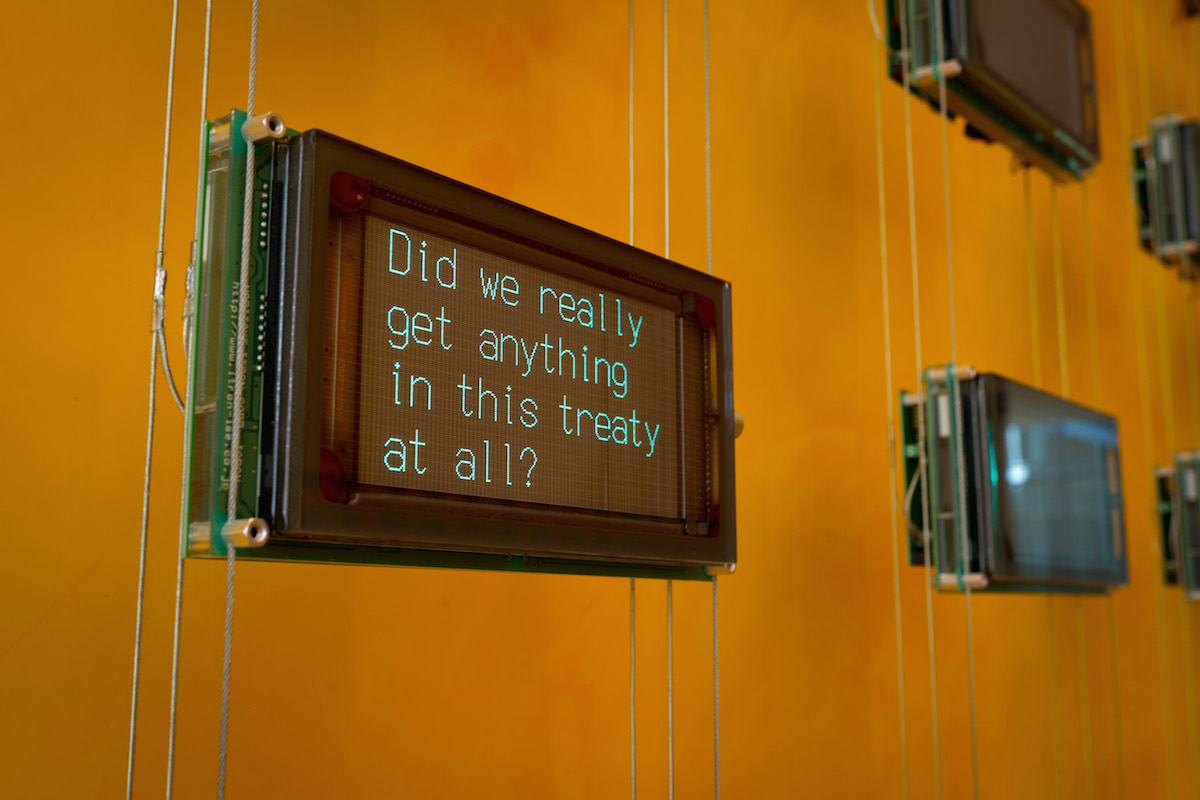

Among other projects, Rubin is the chief creator of the Shakespeare Machine, a chandelier illuminating the lobby of New York’s Public Theater. Each of 37 LED arms streams one of the Bard’s plays, sequenced by a program into poetic fragments. Rubin hopes these are seen as “traces of the incandescent energy, wit and passion that existed at the moment of these plays’ creation.” Alongside their work with businesses and public art projects like Shakespeare Machine, OCR’s co-founders are also currently Artists in Residence at MoMA through the museum’s Artist Experiment, a program run from the Education Department that is committed to developing new ways to engage with the public. For OCR that means making information about the museum’s collection available and accessible in its entirety.

There is an unseen life that MoMA’s 147,000 artworks develop as they are stored in the collection, exhibited and tracked. In OCR’s piece “Thousands of Exhausted Things,” the title, artist, medium and dimensions of every work in the collection has been contextualized through performance. The idea for one scene began in an email from Hansen, a world class statistician. His note contained only a list of names, the meaning of which Thorp and Rubin didn’t initially grasp. This list became a scene performed by a man and a woman: the man steadily reads the names in the sequence, all male, with many minutes passing before the female actor finally interjects desperately with a woman’s name. It is revealed that the duo is reading the first names of the artists in MoMA’s collection, sequenced by how frequently they are represented, teasing out the gender imbalance entrenched in the collection. This archive acts as a kind of cultural history, embodying what might be well-known to students of art history but is largely invisible to those walking the halls of the museum. From data, the OCR once again creates avenues to insight.

In true information-sharing spirit, on the last Friday of each month, The Office for Creative Research invites the public to join OCR Fridays, an informal discussion with an individual or group working at the intersection of data, research-based art and creative methodologies. The events are free and held in NYC.

Images courtesy of The Office of Creative Research