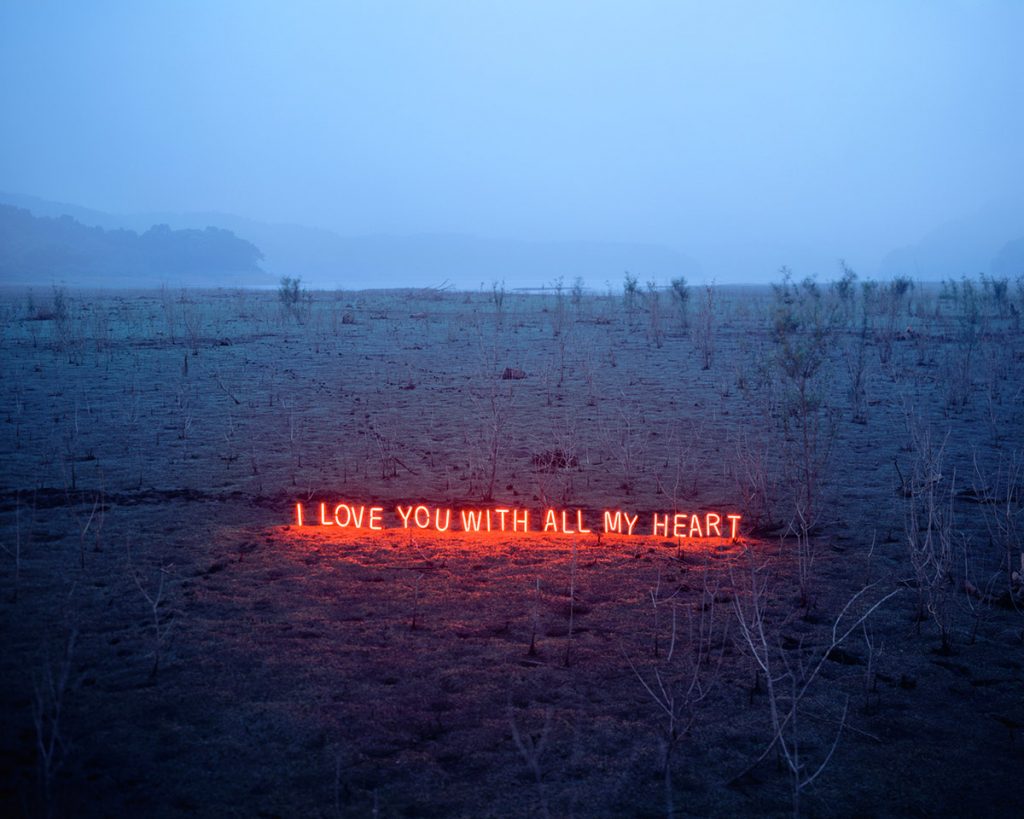

Interview: Jung Lee

The South Korean photographer captures neon thoughts in barren landscapes to convey the limitations of language

Graduating with an MFA from the esteemed Royal College of Art in London, South Korean artist Jung Lee not only studied the theory and practice of photography, but also the art of a foreign language—English. Ever since, she has been probing and wrestling with phrases that haunt her thoughts, from an almost judicial perspective. Perhaps this is why she packs these words and drives them miles from the city, bringing them to deserted areas, into the wilderness. It is in this quiet environment, separated from the rest of the book, the article, the letter, the conversation, where the phrase can take root and grow into something on its own.

While relatively new to the contemporary art scene, Lee has garnered some impressive accolades of late (Artsy named her photography exhibition at Dubai’s Green Art Gallery as one of the top 10 gallery shows of 2013). Lee cites John Baldessari, Bruce Nauman and Sophie Calle as early influences, fellow contemporary artists who are also known for their play with text, pushing the boundaries of the photographic (or neon) medium and also as artists who are not afraid to question whether we should take their work at face value. We caught up with the photographer while she was preparing (somewhat under wraps) for a group exhibition that will be shown next fall in the Netherlands, and found her own words to be as poetic as her artwork.

Your work concentrates on the limitations of language. I’m curious to know if this focus was rooted in your personal experience studying abroad in England, and being immersed in an entirely foreign language?

Although the visa process now is much more particular, in the mid-2000s you could easily spot “English School” signs throughout downtown London, though most have disappeared since. Here in London, people came from all over the world, to find jobs and to learn English. I studied at one of these English-learning institutes as I prepared to enter university to earn a BA, and “language,” or “text,” became a natural interest for me.

As a “multi-cultural” city, London is a charming place; however, living as a foreigner can be a daunting experience. I thought it was funny that the conversations that took place in the English textbooks and at school were ideal and unrealistic. For example, everybody would reply “Fine” and talk about the weather or vacation, their occupations were always “Doctors”… From the perspective of an observer, I could view the gap between language and reality.

Although we use language to express and explain things, I started to realize that those words could never embody everything, and that language could perhaps even be a trap—that was when these ideas started to blossom.

Does your academic background in journalism and broadcasting also have an influence on your artwork?

Because I had studied journalism before I delved into art, things like social issues and the concept of text, for example, naturally were a big influence and became reflected in my work. I’m also the type of person that watches the news a lot.

I like tossing out questions like “Why” into the air and thinking about it. I also like to hypothesize about “If’s” as well. The starting point of a good work is inside the depth of the artist’s experiences and thoughts. But coming from a journalism and media studies background, I think I’m always leaning towards being “objective.” I try to not excessively fall into my subjective experiences and am able to watch from a distance. I think it’s been helpful to work with a slightly cynical perspective.

How do you determine which phrases or sentences to photograph?

First, I have to like it very much—like it enough that even after I pour hours and effort into a work and become exhausted, it still stays dear. I like those words that are common, yet when you mull over them, they also hold some kind of pain, if that’s the right word.

I contemplate over the phrases for a long period of time, until I feel the neon sentences are alive. You could call it “personification.”

I keep imagining and sketching out what the story will become when I place that sentence down in different spaces. And so I wildly keep searching until the scene I have envisioned from deep down, emerges.

I know from personal experience that art education in Korea (and perhaps extending to China and Japan) is very different to that in Western countries. Since you were able to experience both worlds, what are your thoughts on the different teaching methods?

I majored in media and communications in Korea, and in England, art. The most striking part about my art education in England was the fact that you weren’t compared or competing with other people, but first and foremost, I could worry what I wanted for myself, and what I did well, to my heart’s content. As I’m the type of person who has many thoughts and is a bit on the slower side, if I had undergone a Korean-style art education, I think I probably would have become disheartened.

I’m not particularly outstanding with my camera or in the technical department. But in England, my professors kept a watchful eye over us for a long period of time, and the way they valued each student’s individuality made a deep impression on me. Even though this might be considered a childish or trivial thought–they always saw the potential. I learned a lot about having a mental attitude of not giving up or making judgements easily or swiftly in regards to my work.

Because Korean education is especially sensitized towards comparison with others and ranking, etc., the tangible praise and recognition in the short-run cannot help but be our weakness. But an artist’s path is like a long marathon, and I think you can only run tirelessly if you listen more attentively to what’s inside—the less tangible—and rise above by battling with yourself.

This is probably not the first time you’ve been asked this question, but how do you feel your work compares to other notable artists who work with neon such as Tracey Emin or Robert Montgomery?

Ultimately, my work is expressed through the form of a photograph. The audience doesn’t directly view the neon itself, but sees the neon inside a scenic landscape. I believe that neon in this scenery, represented through a photograph, plays an absolutely different, new role from the neon that we see in our reality. In the real world, neon’s character is to shed light and its role is to deliver a message. But in these photographs, the neon’s role is more prominent.

In my case, the neon unites with the landscape and creates a third story. Neon settled on snow-covered ground, or floating on top of the ocean—these are realistically impossible scenes, but if anything, these scenes have this kind of appeal that arouse the audience’s stored memories or imaginative thoughts.

The audience is not looking at a message from the artist when they read the neon sentences; instead, they face their own inner “voice.” This point, I think, is the greatest difference.

Interview translation by Nara Shin

Images of artwork and self portrait courtesy of Jung Lee