Sighthouse

Repurposed projectors, stereoscopic photographs and light play in Jonathan Bruce Williams’ debut exhibition

Walking into the gallery space, the whirr of two continuous projectors greets guests alongside indistinct color images that shower the room from a twirling projector. Every few seconds, four snaps are heard corresponding with sequential flashes of light. The interior is dark and filled with a thin smoke that emanates from the tower of the main installation, giving the space the atmosphere of a film noir set.

This is the scene at “Sighthouse,” the debut exhibition at Franklin Art Works by Minneapolis native Jonathan Bruce Williams, which runs through 17 November 2012. The young artist has erected a trio of installations that play with photographic history, the physics of light and the notion of a lighthouse. Following his graduation from Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD), the artist has met with success as the recipient of the Jerome Fellowship for Emerging Artists and as part of a group show at MCAD. Leveraging the opportunity at MCAD, Williams presented a model of “Sighthouse” for the Franklin Art Works space that impressed curator Tim Peterson—enough to warrant a two-month-long extended solo show at Franklin.

Williams comes from a background in photography, though “Sighthouse” feels more like the work of an engineer than a shutterbug. A mass of camera equipment—pilfered from the remains of a local production house—has been stripped, modified, rejiggered and finally refined for the installation. Everything is analog; even the animated GIF for the model version of “Sighthouse” was shot using twelve 4×5 frames from a view camera on a ten-minute exposure. The high-level execution and polished aesthetic make Williams a formidable talent in multimedia, and one to watch in the coming years.

“I’ve always created these scenes that are constructed from a dark corner space that is sort of nondescript.”

The title piece, “Sighthouse,” takes the form of a skeleton house and adjoining tower, which have been painted with a gradient to reflect the properties of light. In both the tower and the body of the house, 16mm projectors run on continuous loops. They have been modified for function and aesthetics, the ’70s teal paint stripped to reveal a more contemporary aluminum body. The video below shows a piano being disassembled at 24 frames per second, a sequence that is randomized to trick the eye into thinking that it is seeing both the exterior and the interior of the piano simultaneously. Below the video loop, subtitles related to notions of time cycle in likewise randomized intervals.

Up top, the bare bones of a projector rotates around and casts the colorful, vague images that define the walls of the room. The casing has been stripped to such an extent that streams of light emerge from the sides and rear.

A pair of silver gelatin photographs make up “Light Keeper’s Quarters,” a stereoscopic installation that uses 90-degree mirrors to create the effect of a 3D image. Unlike anaglyphs, which use colored filters to create the 3D illusion, Williams’ stereoscope yields a remarkably crisp image of a room that is inspired by the dormitory of a fictional lighthouse keeper.

“I’ve always created these scenes that are constructed from a dark corner space that is sort of nondescript,” says Williams. “And there are always things that are absent in these scenes, or things that are dissolving or appearing or otherwise being disassembled. The composition for “Light Keeper’s Quarters” has this window and these strings coming from it that suggest where light would stream in through the window, but there’s nothing there.”

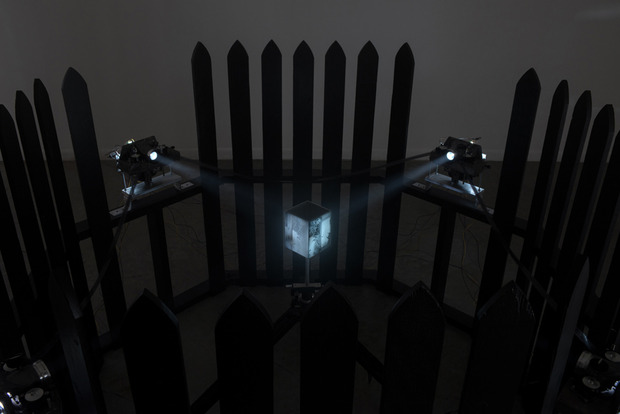

In “Shadow Fence,” four inward-facing projectors surround a cube that has been coated with phosphorescent paint. Williams replaced the hot lights with flashes from point-and-shoot cameras, which strobes every seven or eight seconds, burning an image into the cube. The photograph is of a backyard, which was shot by outward-facing cameras—inverting the panorama by projecting it onto the cube. Continuing the notion of randomization, the order of images rotates with each flash.

Read more about the exhibition in Williams’ own words after the jump.

You have all of these symbols—the fence, the house, the room. What’s behind all of these references to interior spaces?

It’s a domestic sensibility, I guess. It comes directly from the place I live and what I have read into the house. It was a foreclosed property, and I feel that this situation is something that can only happen for people who are my age right now in that the market tanked and there are all these pieces of property that are just sitting there. In the same way that I’m dealing with all of these old, discarded movie projectors that nobody wants anymore, I’m also dealing with this old house that nobody wanted anymore. There are a lot of things I’m interested in photographically and technologically, but I think a lot of what art is comes from primary experience—just what happens in your life.

The picket fence is a subversion of the American dream of a white picket fence—really simply because it’s painted black. But there’s also this historical scientific observation of a passing train through a fence structure that led to the development of a zoetrope, these childlike toys that led to the development of moving pictures. It’s finding these symbolic intersections that I’m really interested in.

What is your relationship to camera mechanisms, projectors and all of these defunct technologies?

Taking apart something is really easy to do and really pleasurable to do for people who are mechanically inclined. Putting something together and having it function in the same way or better—that’s where things get tricky. I got a whole surplus of movie projectors from this production house in Minneapolis, which has allowed me to study these mechanisms. So I’m at a point where I know what breaks, what gets dirty and needs to be cleaned, and how to completely overhaul these devices—all because I’ve been able to work through so many of them. I think that from that sense of studying I’ve also developed the mindset of an engineer who might have designed one of these things, and I get to apply that knowledge to my own designs.

“Sighthouse” is showing at Franklin Art Works in Minneapolis through 17 November 2012.

Images courtesy of the artist