“T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America” at the National Museum of the American Indian

Bold, political, multidimensional and wildly important works by the visionary artist

After fostering his talents at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, T.C. Cannon entered the art scene with a vision to subvert traditional perceptions and dismantle stereotypes surrounding native art. He did so by combining historic, traditional motifs and images with his own distinct, contemporary style. Though his life was cut short by a car accident at age 31, Cannon left behind a wealth of work—some of which is on display in NYC now. T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America, an ongoing exhibition (and the first formal presentation of his work in over 30 years) at the National Museum of the American Indian, features his poetry, music, paintings, wood etchings and works on paper.

The expansive collection was amassed by Karen Kramer (the curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts) through personal donations, public collections and by tracking down works that were located by Joan Frederick in her 1995 book T.C. Cannon: He Stood in the Sun. A few more pieces were added by Cannon’s sister, Joyce, who had retained most of his poetry and has managed his estate since his passing.

“[The diversity of his work] adds to the experience because it makes for a more well-rounded understanding of T.C. Cannon and how inextricably linked music, poetry and painting were for him,” Kramer tells us. “He couldn’t have been the painter that he was without the music, and he couldn’t have been the poet that he was without the painting. It’s all interconnected and I feel like those connections become palpable when you walk through the space.”

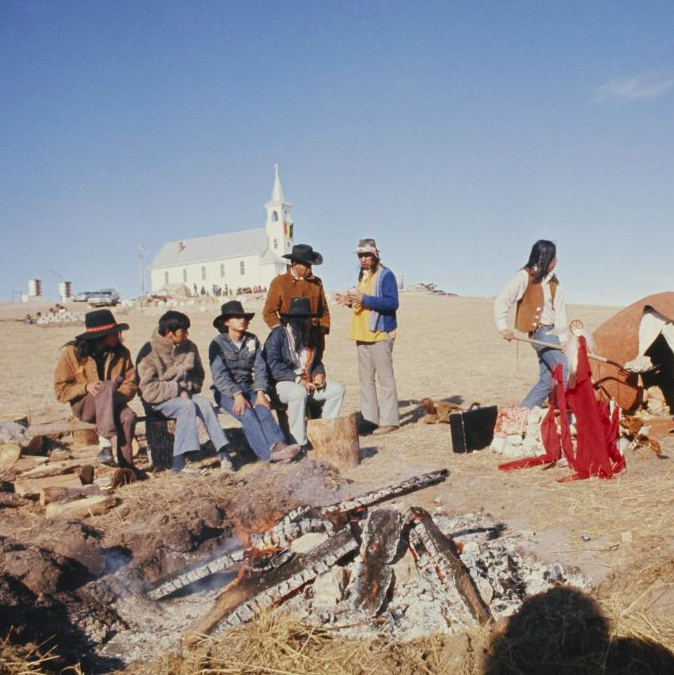

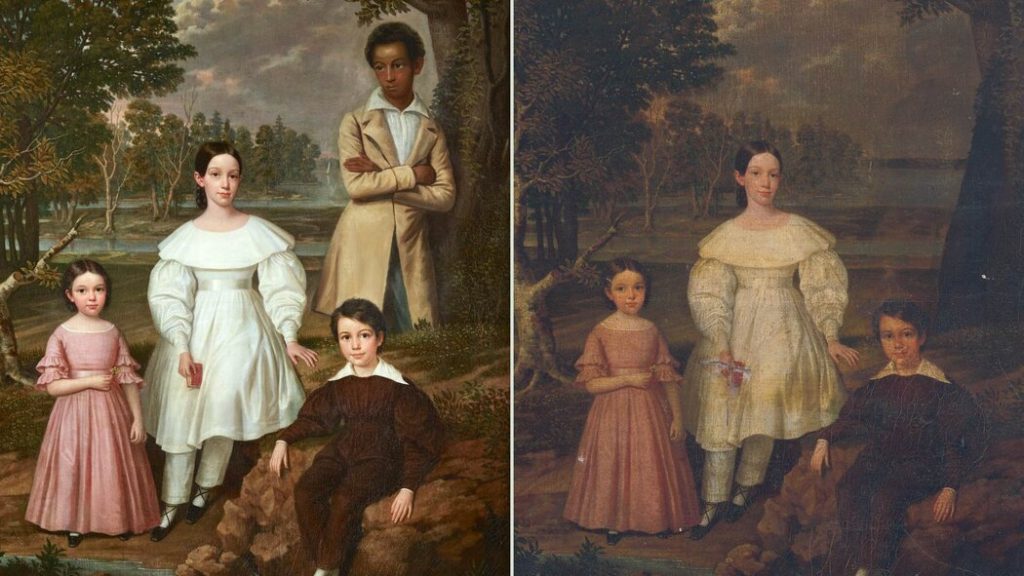

“One of the things that I love in T.C. Cannon’s work is that he’s taking some of the imagery of native people that might be familiar to our audience: those romantic, 19th century black and white portraits that people—more generally speaking—might be more familiar with than even Native American history at large,” she says. “People might be familiar with a picture of a Native American warrior, for example, and he serves it up to us larger than life and in technicolor. So some of the imagery is going to be familiar, but what he does with it is what’s so exciting and so unexpected.”

During the tumultuous ’60s and ’70s, Cannon intertwined white American and Native American histories into pieces that subverted the traditional scope of traditional Native America art. Influenced by Bob Dylan and Vincent van Gogh, he created works across many mediums. Perhaps most indicative of his influence, his mentor Fritz Scholder became well-known for imitating one of Cannon’s works for his painting, “Indian With Beer Can.” Scholder rose to stardom in the ’80s (a long time after Cannon passed away) while Cannon’s work was rarely shown in public exhibition spaces, and his pieces were scattered throughout private collections. On “Indian With Beer Can,” Kramer says, “There are a lot of misgivings about it because T.C. is the one who did it first, but Fritz kind of riffed and got all the glory.”

“Contemporary native artists today have shared with me that they’re quite inspired by T.C. Cannon’s vision and his voice. They’re inspired by his bold color and his intermixing of native and non-native elements. They’re also inspired by his willingness to be political and to be an activist through paint and words and music. I think that still carries through to today,” Kramer says.

Though Cannon may not have always received the attention that was warranted, with T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America his bold and thoughtful work gets the comprehensive show he deserves—thanks to the National Endowment for the Arts, Joyce Cannon Yi, the Peabody Essex Museum and the Lynch Foundation. The exhibition is a stunning and breathtaking look at this visionary artist’s work—and not a moment too soon.

Hero image of “Epochs in Plains History: Mother Earth, Father Sun, the Children Themselves” (1976-77) courtesy of Gary Hawkey for the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture on behalf of the estate of T.C. Cannon, all others by Evan Malachosky