Interview: Postalco Co-Founder, Mike Abelson

We discuss Japan’s collaborative community, designing for your own curiosity and owning less

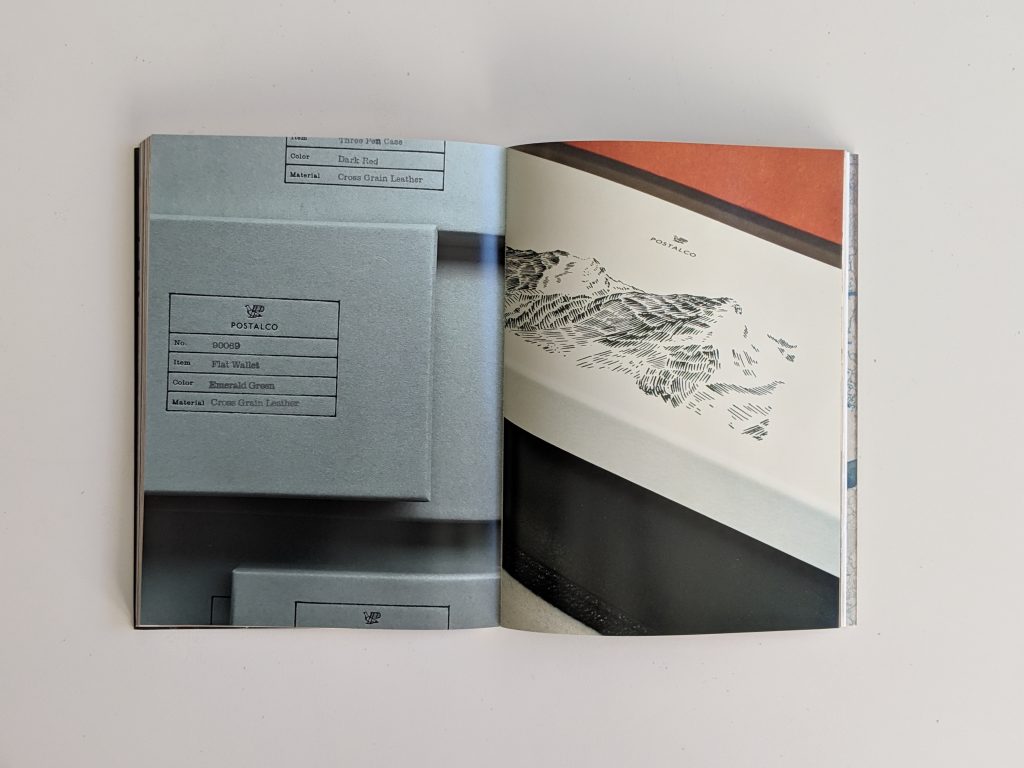

Since their conception in 2000, Postalco has moved from Brooklyn to Tokyo, collaborated with dozens of brands and built out their collection to include everything from wallets and pens to outerwear and furniture. Founders Mike and Yuri Abelson have applied their clean aesthetic style–influenced by the Japanese attention to detail—to a number of mediums and projects. They have even produced a book—Swimming in Puddles: Questioning and Making at Postalco—on the discoveries, products and questions they’ve encountered along the way. We were able to meet up with Mike during his latest New York visit to discuss Japan, collaborations, the book and more.

We’re celebrating your 18th anniversary, sort of. Why did you decide to do a book?

Well, we were approached by this publisher, and they wanted to just feature our finished work. But, we thought it’d be a lot more interesting to really go into the stories of how we made things and how we experimented with different craftsmen, traditional Japanese ways of making and try to bring a different, sort of Japanese looking approach to those traditions. We really wanted to dig into stories and make it a book of stories.

And the story is focused on those different people, and methods, that you developed your products with?

Our personal experience, over and over again, has been like, “Oh, that’s sort of interesting, but it doesn’t look that deep.” And then you start to get into it—for example, paper-making. I know Washi, and it’s kind of common to see Washi around in different places. But, I never really got into it that deeply. And then, when we started making it, we had this idea to make Washi that would replace leather for wallets. Then really diving into what that Washi would be like, and then working with this eighth-generation master craftsman. Then Washi just opened up into this huge possibility. So, at first, what looked like just the equivalent of a thin little layer of water—like a puddle—at first, until you actually dive into, becomes this huge ocean of possibility. That process happens over and over again with a lot of different categories. That is what we find exciting. And, that’s what keeps us in Tokyo. Just because there’s always more layers to peel back.

It’s really just this chain of flowers where you keep walking down the path and keep finding new flowers.

We briefly talked about how, in some cultures, you meet someone and instantly you have access to their studio and insights into their craft. How have you found that experience in Japan and how is that different?

We found that—at first—in Japan, you’re either “in the group” or “out of the group.” It’s stereotypical, but at the same time there is an element of truth to that stereotype. I feel like once you’re inside of a group, then people are very open and flexible and talk about different things. So, when we first went, we started with one small wallet factory, and they said, “Oh, we know this guy; he makes boxes. Do you want to meet them?” And we went to the box guy, and his cousin makes leather. It’s really just this chain of flowers where you keep walking down the path and keep finding new flowers. Pretty soon you realize you’re in a totally different area, and you don’t know how you got there, exactly, but then all of a sudden we’re making rain gear and we’re making pens and working with metal, leather, paper—there are just so many layers to discover.

But, at the same time, we were surprised that there’s not a kind of relationship with the craftsman where the customer is above the craftsman in any way at all. And the first thing they’ll tell you is, “I’m really busy. I don’t need your work. But, if you want to wait, we can try to do something.” As long as you’re not in a rush and open to hearing their thoughts, then the idea that they’re working for you just doesn’t exist. It’s like you’re really doing this thing together. That’s very different from typical US supplier-consumer relationships.

It’s not rude, but it’s just an “I don’t need your business” kind of thing—would you say?

I think it’s really about considering, mutually, what’s good for everybody. I really feel like though, a lot of companies are happy with the scale they’re at—they’re not trying to take over the world or expand incredibly. The majority, I think, are craftspeople who are more concerned with keeping the quality they have, continuing their relationships with their customers, and they’re really happy if you’re willing to take the time to understand their concerns and work together with them. You can create amazing things that way.

From a desire and demand point of view, are these products you want that aren’t out there that you’re making, kind of, for yourself? For instance, you’re doing clothing now and outerwear. Is that because of existing customers saying, “Hey, it’d be great if you also branched out from paper goods to also do outerwear?”

We do have a really wide range. I think it’s because our main motivation for making things is to make things we feel that we wanted, but we couldn’t find exactly. Because of that, once we have a wallet that I really like, we try to make these things last as long as possible. I have a wallet I like that I’ve been using for years. So I don’t have the desire to keep making hundreds and hundreds of wallets. We tend to branch out horizontally into other categories where we feel like something is missing. Sometimes it starts with an amazing material or manufacturer or craftsman, and we see that and we feel we can do amazing work together. Another part of it is that I really feel like one rule of design is trying to find a way to give traditional techniques a new way of being in the world.

I guess I’m obsessed with things I touch every day. I just like the things I touch every day should be something really special—like when materials age well. A lot of these traditional crafts are based on finding ways to make wood age well and not crack; or leather age well, so it’s sewn in a way so corners develop a great patina. Those are really traditional techniques that you don’t notice when you buy them, but they emerge over time. We wouldn’t know these techniques but in speaking with these craftsmen, they’ll go, “Well, if you’re going to make the paper it really has to be pH neutral. Otherwise, it won’t hold up over time.” It’s things like that that you would just never know. But it’s part of their experience from working over generations.

I just feel like having less and less, but I really want to love the things I have. It just feels lighter.

The brand is really informed by certain sensibilities, but really leverages Japanese heritage craft skills and perfectionism to create your products. How do you perceive that mix?

I think just being in Japan, and really working with craftspeople, we learn so much from them. I feel really lucky. I feel like I learn stuff every week, every day. Being in Japan every year, there’s some new layer that I didn’t know existed. I also think it’s baked into people’s approach to making things. So that sort of precision and making things is done as perfectly as possible. Those things that people associate with Japan really exist in a way. It doesn’t feel confining though. It feels really, almost in a weird way, liberating. People just don’t want to waste things.

I think a lot of times the making of products is driven by trying to find another to sell without necessarily thinking if it really has a reason for existing. Maybe I just feel like having less and less, but I really want to love the things I have. It just feels lighter.