Studio Visit: The Principals

The Brooklyn-based group designs everything from dominoes to shop interiors and high-concept installations

What does a studio—one that turns out a broad range of projects that require attention to the most finite details as well as broad strokes and big picture ideas—need? Balance. And after what The Principals founders Drew Seskunas, Charles Constantine and Christopher Williams describe as a somewhat shaky start, they were able to ground their young studio. Formed just two years ago, the first step was putting their “designer egos” aside and pooling their talents into space-transforming installations for PS1, Model Citizens gallery and Bonnaroo, as well as products like the Bronze Bones dominoes—which later became Bare Bones, a set created in collaboration with fashion designer Billy Reid.

The group’s eclectic backgrounds contribute to their varied style. Seskunas (who grew up with Constantine in Baltimore, and was later his classmate at Pratt) hopped around Europe after getting his Masters in architecture. He eventually stayed in Berlin long enough to direct the office of SAQ Architects, which was awarded the sought-after land design commission for the controversial Bikini Berlin downtown renovation project.

Meanwhile in Brooklyn, Constantine (who studied industrial design and has a background in sculpture) was working at landscape design and fabricator PlanterWorx, where Williams was the shop foreman. After three years of churning out planters, they decided to strike out on their own with Seskunas—who had since moved back from Berlin and was waiting for them to give notice, so the three could officially start working together as The Principals.

After creating a series of simple home furnishing (chairs, a coat rack and a waste bin) their first major project as a studio was the Botox Lamp, an installation they put together in just 24 hours and shipped to Berlin for DMY (Berlin’s design week). Even though it was a last-minute project, the Botox Lamp was crucial to cementing the studio’s goals and their working relationship. “We had only really worked together—the three of us—for that one 24-hour period,” Constantine says. “We were still really green as a studio, so we were trying to produce as much as possible. Every idea mattered. All of those were exercises in making compromises and figuring out how to work with each other, regardless of whether we tried to sell something or just made something and that was the end of it. The experience we gained from going through that is what was important.”

After returning to New York, The Principals worked steadily. “We had a lot of ideas of where we wanted to go,” Williams says, “but the thing that brought it together was that we all wanted to make cool stuff and have fun doing it. Some things fell in our lap and some things took some doing, but they all led us in the direction we’re going in now.”

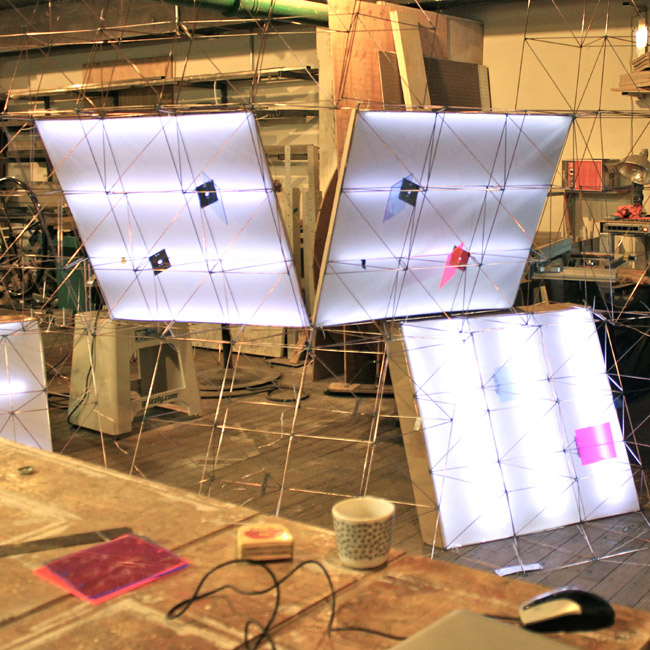

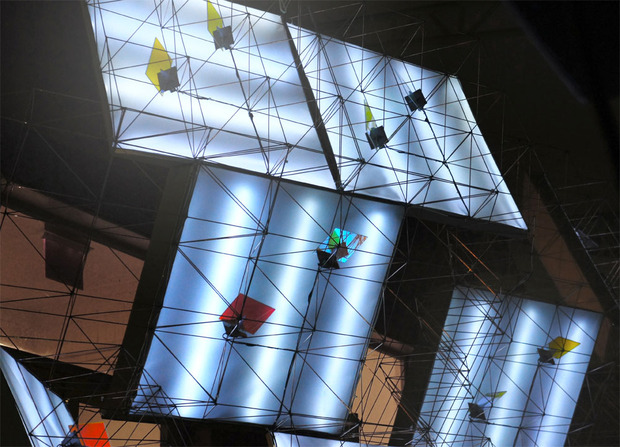

There was more furniture for their “Family” series, small tables commissioned for a Sight Unseen pop-up, shop interiors for Everlane, the leather-bound Bronze Bones domino set and increasingly more complicated installations—like the responsive, Arduino-based canopy, Cosmic Quilt. “We always want to take any project and maximize it to its fullest potential,” says Seskunas. Everything we do, we do 110%. We worked 80 hours a week each for about the first eight months of the company, taking any project that would come through. We refused to say no to anything.”

Following up on our previous meeting, we sat down with The Principals in their Greenpoint, Brooklyn studio to talk about working with wild animals, why starchitects are a dying breed and how to sacrifice yourself for your craft.

With such a broad portfolio, how do you describe your practice?

Seskunas: It was really difficult in the beginning. Even just talking to insurance people and trying to describe what the business would be. We didn’t know. They would ask us, “Are you artists? Product designers? Fabricators?”

Williams: We’re insured as a traveling circus. [laughs]

Constantine: But it’s not something we need to think about anymore. Our roles happen organically and everyone knows what they’re going to do. Everyone seems to gravitate towards certain roles. In the beginning, I personally would fight that and say, “I have to be in on this decision.” But now it’s much more open.

When we finally made something together; it’s like, “Jesus, I could never have done that by myself.”

So authorship is no longer important?

Seskunas: Nobody who becomes an architect or designer doesn’t have an ego. You want to force your will on everyone else. I don’t know a single architect who’s not a massive egomaniac—myself included. That’s why we work as a collective, because it’s not a productive trait. I think we all struggled with that, and it’s why we went into this kind of organization; to wear down those hard edges. But that was kind of the fun part—the fireworks that occurred in the beginning. We look back on it fondly now and can laugh about it. Now things are so much smoother.

Williams: We all came into this with opinions of how strong we each were at what we did. And then when we finally made something together; it’s like, “Jesus, I could never have done that by myself.” It was humbling—and it made it easier to dissolve the ego and focus on the group. Anything I’ve done with these guys versus what I’ve done by myself—it’s just not as good.

Is the group effort a direction you see more young designers going?

Seskunas: Yes, authorship is irrelevant. I think more people are realizing that—it’s certainly something we try to convey to our interns or in the workshops we lead. You still see people like [Jean] Nouvel or Frank Gehry, but in 20 years those people will never exist. You’ll never see someone from our generation like that. It doesn’t work anymore. Our culture doesn’t need it. Economically it doesn’t work, and the way things are produced now it doesn’t work either. But it’ll take generations for it to wash away.

Do you think it hurts your brand to not have a recognizable aesthetic that runs throughout your work?

Seskunas: Not having authorship in that way may be career suicide, but making everything have your stamp on it is boring. The white geometrical shapes [for Everlane‘s stores] is not something we would ever do for ourselves, but it worked so well for their brand. We want to understand what the client wants and help them do what they can’t do themselves.

You’ve had a lot of success with Bare Bones, the more affordable version of the Bronze Bones dominoes. How did you translate the bronze set into concrete?

Constantine: Small-scale products are the most exhausting. We worked on Bare Bones for an entire year. There are so many variables you don’t think of at first—the packaging, the shipping…

Seskunas: Nobody gave a shit if we did this project. We did it because we wanted to do it. We said, “We will only put this out if we’re 100% happy with it, no matter how long it takes. We’re going to make everything. We don’t want anybody else to do anything.” So we spent six to seven months just analyzing it until it couldn’t get any better. It was economically viable—we could make them and not lose money—and we can make them all in-house.

Williams: And then we had to figure out what the rules were going to be!

Seskunas: There’s not one way to play dominoes; there are like, 8000 ways.

Williams: And there’s the way we invented. For the tournament at Billy Reid [as part of Noho Design District earlier this year], we had really experienced domino players and people who had never played before, and of the first and second place winners, one person never played a game in his life and the other one was very experienced. So our game apparently worked pretty well—it leveled the playing field.

You recently staged Spatium Yamamoto for MoMA PS1’s Summer Warm Up series. It seems like no matter what other projects you work on, you always come back to interactive installation design.

Seskunas: Installations make you rethink how you define space at the most basic level. What’s space? What’s architectural as opposed to installation? What’s a room? The first space we made that you could technically define as architectural space was Cosmic Quilt, because it had four posts and a pavilion roof, like a shelter.

The biggest problem with interactive design is that people refuse to accept that it has any impact on architecture, critically. People don’t take it seriously. They don’t see it as part of the conversation. It needs about 20 years of gestation before people will consider it as serious. To try to give it that legitimacy you have to relate it to architecture historically. So we go back to those definitions of space, the Vitruvian ideals of the five points of space and how Le Corbusier defines space. What are those elements? Cosmic Quilt has space frames that run to the ceiling, but they serve no structural purpose. We’re looking at it critically and thinking: This is normally a functional piece, but we’re treating it as a piece of artwork—rendering it non-functional.

So then it’s not architecture—technically?

Seskunas: The desire to create something functional because you can’t create something beautiful—that’s bullshit. That’s architecture.

Do you have any favorite projects?

Williams: My favorite is Cosmic Quilt. It was our first large project together out of my realm of expertise. We got to work with a lot of students and we cranked it out in two days. But, I love Bronze Bones. They’re beautifully made, the packaging is great and we all had a part in it. But they were so expensive! If you want to determine if a project is successful by how much it sells, then that project is a failure, but it says a lot about our studio that it was one of our earliest projects and we just kept moving. It can be kind of discouraging for a young studio to stumble like that in the beginning, but we used it as a learning experience.

Constantine: We actually don’t talk about favorite projects a lot, even just amongst ourselves. We really kill ourselves over everything we do. I don’t want to say other people don’t, but we go to the “nth” degree—and then some—and I’m super proud of every project we’ve done.

The Principals are growing their portfolio with several interior design projects, including Everlane’s new San Francisco office and two restaurants—Casa Blanca in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn and Knickerbocker in Bushwick, Brooklyn—scheduled to open later this month.

Photos by Perrin Drumm