The Watermill Center’s Summer Benefit and Artist Residency

Exhibitions by Christopher Knowles and Robert Nava support a chic occasion that was themed “Stand”

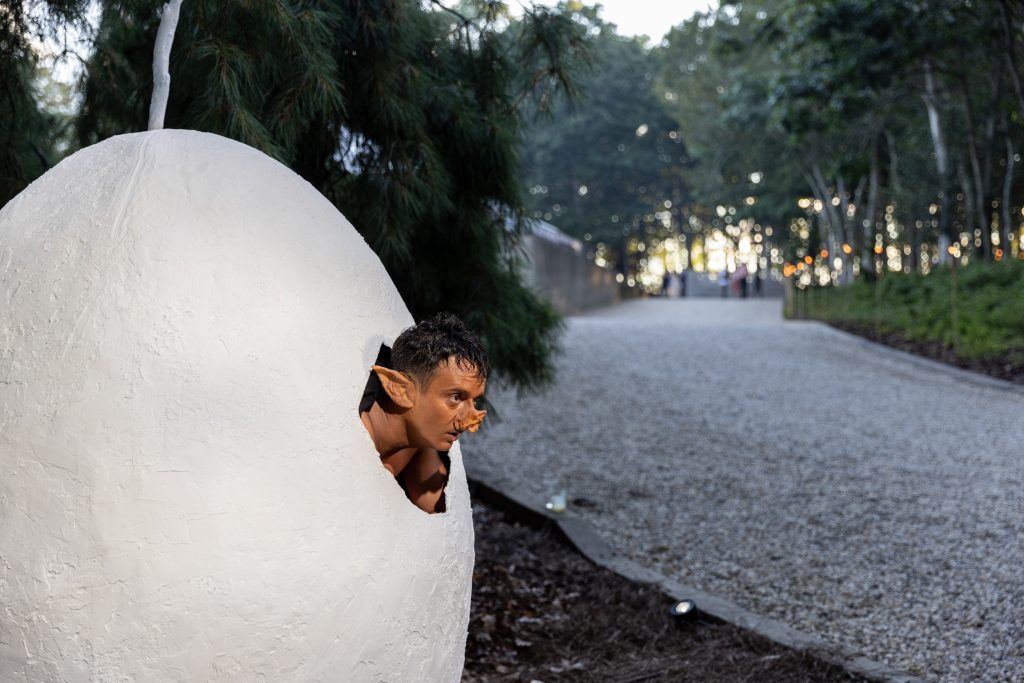

As with so many other art institutions and residencies, The Watermill Center is working its way back to full capacity after 2020 and 2021 led to a reduction of residents and guests at events. This summer, the property hosted a chic benefit that more than doubled the invitations they sent last year. The occasion, one of the most talked about on Long Island’s East End, was held on 30 July and celebrated their 30th anniversary with two resident exhibitions and a performance that saw an artist popping out of a large egg.

The benefit’s title, Stand, represented more than just a gala theme. The elegant event was divided into two acts inspired by an H.G. Well’s quote stating, “If you fell down yesterday, stand up today.” For where we are in America now, there might not be a better or more apropos title. Act I featured various performers and installations taking place on the property. For Act II, those present were invited to participate in lifting a wooden sculpture entitled “Manhattan Go” (2022) by Japanese artist Tsubasa Kato. Utilizing a pulley system designed by the artist, the intention of the work was to go from a horizontal position to a vertical one. This was followed by an audio work by American composer and pianist Matthew Shipp.

As for the exhibitions featured during Stand, one was from Christopher Knowles (a long-time friend and mentee of Bob Wilson) and extends to the end of the year, while the other was from Robert Nava (who is represented by Pace Gallery) and closes Labor Day. Knowles and Nava were given space on the property to work and both proved to be very productive. Nava, the Inga Maren Otto Fellow, approached his time at The Watermill Center with an open mind, removing pressure to create and filling the studio with works on paper.

“I didn’t really know about the Watermill Residency but I found out about it through [Watermill Curator] Noah Khoshbin,” the artist tells COOL HUNTING during a visit to his studio. “They didn’t expect me to do anything at all. I thought maybe I would make one drawing and one large work on paper and that’s it, that’s the work. But I can’t help it [gesturing toward studio walls lined with large-scale paintings that extend onto a nearby table and even the floor]. I love painting and I just like making things wherever I am.”

Nava worked in his Watermill studio with the full wall of doors and windows open (even in the blazing heat). “In my old Bushwick studio, I would spray paint on the roof, where the blowing wind would bring an unexpected element to the process,” he continues. “I love the sky and working outside allowed me to be in control and out of control at the same time. I try to ride that…without falling off.”

In his new work, the balance between space, objects/subjects (in this case hybrid animals) and surface markings allow one to recognize the movement of his body through the gesture. “Inside,” he continues, “I have control and use spray paint with the lowest pressure caps and like what the line does. All that said, imagination might be the most important.”

Not dissimilar regarding production and making work, Knowles, a prolific, self-taught artist with autism, extracted artworks from his archive and Wilson’s extensive personal collection for this show. Ranging from 1974 to present, Knowles worked up until the summer benefit, with in-process Lego sculptures in the dining room on the ground floor and large lego frames in the second floor gallery. Unlike Nava who works mostly two-dimensionally using crayons, acrylic, Montana Gold spray paint and oil stick—Knowles makes paintings, but is most known for his typewriter drawings, found alarm-clocks that unexpectedly ring, Lego sculptures and color-coded paper layouts.

There is something to be said of the entire Stand experience, and the most important takeaway might be just the opposite: movement. After what has felt like two years of standing still, we are once again being invited to move—and without proposed rules or expectations. For even if the dance (or painting) doesn’t follow predetermined steps, it still might be the most beautiful action ever performed.

Hero image courtesy of The Watermill Center