Climbing the Wall: Melissa Joseph, Baseera Khan, and the UOVO Prize’s Expanding Legacy

We interviewed artists Melissa Joseph and Baseera Khan to dive deeper into their practices and the impact of the UOVO Prize on their careers

Since it was launched in 2019, the UOVO Prize has become an influential platform for emerging Brooklyn-based artists. Created in partnership with the Brooklyn Museum, the Prize offers more than visibility. It provides a solo exhibition at the museum, a 50-by-50-foot mural on UOVO’s Bushwick facility and a $25,000 cash grant. Over the past five years, it has consistently helped artists turn local recognition into national and international careers.

Melissa Joseph, 2025’s recipient, recently unveiled a mural at UOVO’s Bushwick facility and a site-specific installation on the front steps of the Brooklyn Museum. Her work transforms everyday imagery into poignant meditations on identity, memory and belonging. Joseph is known for using materials such as felt and textiles to reanimate personal archives, especially those related to her family and South Asian heritage. Through this tactile practice, she brings intimacy to the public realm and expands what is typically considered worthy of monumental representation.

Joseph’s approach fits within a lineage of UOVO Prize recipients who use personal experience as a lens for broader social themes. One of the most impactful artists to receive the award was Baseera Khan, whose 2021–2022 cycle marked a turning point in their career. Their solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, titled I Am an Archive, included sculptures, installations, collages, textiles, video and photography. These works tackled the entangled forces of surveillance, cultural erasure and structural violence.

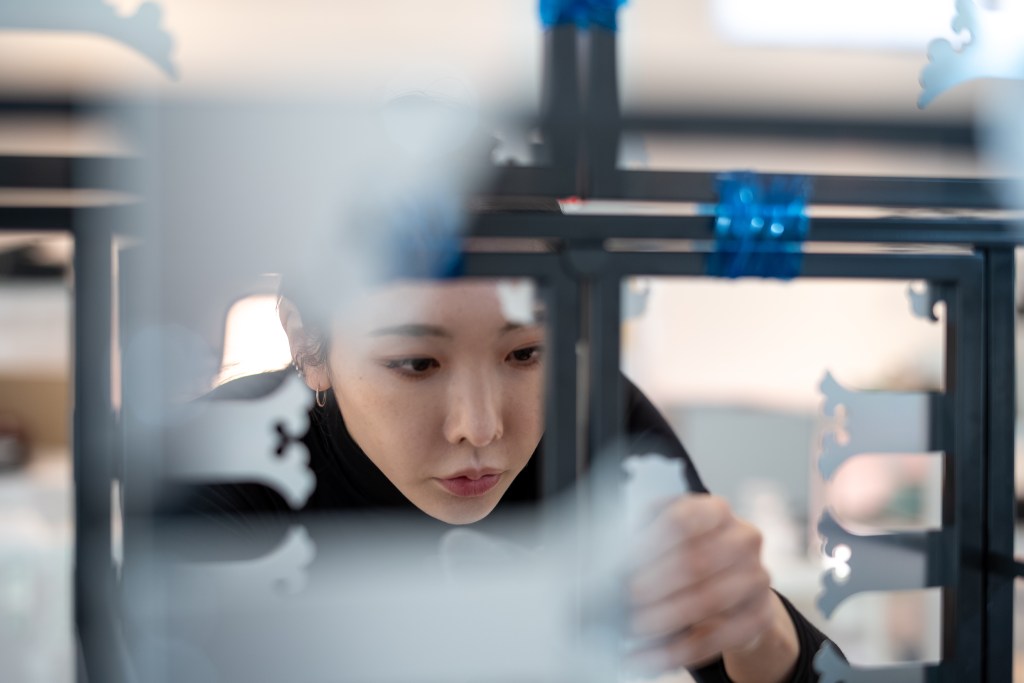

Khan’s mural at the UOVO Bushwick site featured a striking image from their performance Braidrage. The piece shows the artist climbing a wall made from resin casts of their own body, incorporating gold chains, hypothermia blankets and imported hair. Using indoor rock climbing techniques, Khan created a metaphor for resilience in the face of personal and collective trauma. The mural captures them mid-ascent, gender obscured, leaving charcoal marks as they climb. It stands as a powerful act of resistance and reclamation.

Since receiving the UOVO Prize, Khan has continued to build momentum. Their work has been featured in several high-profile exhibitions, including The Liberator at the Hirshhorn Museum, Floral Fix at Simone Subal Gallery, and Pocket Diary at Niru Ratnam Gallery. They were also commissioned by the High Line for a public installation and have joined the permanent collections of institutions such as the Whitney Museum, Guggenheim, Walker Art Center and Brooklyn Museum.

The UOVO Prize has played a formative role in the careers of artists like John Edmonds, Oscar yi Hou, Suneil Sanzgiri and others who have gone on to gain critical recognition and institutional support. What sets the prize apart is its commitment to placing emerging artists directly into the civic and cultural fabric of New York City. By combining museum visibility with large-scale public art, it invites audiences to engage with complex narratives in both intimate and monumental ways.

Joseph and Khan each offer a deeply personal lens through which to view the world. Their practices remind us that art can make visible the stories often left at the margins. Through the support of the UOVO Prize, those stories are not only being seen but placed at the center of our shared cultural conversation.

We interviewed artists Melissa Joseph and Baseera Khan to dive deeper into their practices and the impact of the UOVO Prize on their careers.

Our Conversation with Melissa Joseph:

What first drew you to working with felt and textiles as central materials in your practice?

Melissa Joseph: I was drawn to textiles because as a child, that is what I had access to, so I learned to be a maker with craft materials.

Your mural and museum installation both explore deeply personal themes. How did you approach the challenge of translating intimate experiences into public art?

MJ: I think there is a level of distance that comes through the interpretation of the images. I don’t normally show the actual photos, which are so personal and dear to me, but in recreating them I feel like I can share the universal sentiments while maintaining a bit of distance from my own life.

Your practice merges sculpture, photography and craft. Do you consider your work grounded in a particular tradition, or do you intentionally move across categories?

MJ: I intentionally move across categories because I believe they are all constructs. It aligns with my feelings on race and borders. These are arbitrary categories that are imposed on a larger whole. That doesn’t mean, though, that I don’t believe that they impact how we are able to move in the world. It’s just my larger philosophical view.

Some of your pieces incorporate humor or a sense of play. How do you see those elements functioning alongside themes like grief or nostalgia?

MJ: Grief is always present — the older I get the more it becomes a constant companion. Humor feels like it’s often born from that grief, in a way, as a relief. I think there is a whimsical nature inherent to my materials that tempers any sentiment from overpowering the experience, whether it’s sadness, joy, nostalgia or even tenderness.

What impact did the UOVO Prize have on your work and visibility? Did it change how you view your place within the broader art world?

MJ: This prize has been such a gift. It’s opened up new lines of inquiry while letting me understand new ways the work can live in the world at a much larger scale.

The Brooklyn Museum installation is located on the front steps, a public and transitional space. How did that setting influence your vision for the work?

MJ: I consider public art to be somewhat non-consensual art, in that people walking by or living near didn’t necessarily ask to encounter it. They can choose to go inside a museum or gallery if they want to engage with artworks. It impacts how I think about the imagery I want to put forward; some of it feels more suited to a broader audience. I hoped many people can find something to relate to in these images of care and love. It’s why I wanted to make so many individual images, rather than one large one.

In contrast to the fast pace of digital culture, your work often emphasizes tactility and slowness. Is this an intentional counterpoint?

MJ: Yes. I am not a digital native. I learned to think through my hands, and no matter how advanced technology gets in my lifetime, I will always return to working with my hands to understand the world.

How has your understanding of the concept of home evolved through your artistic process?

MJ: My art practice is my home, which might be why I cling to it so dearly and fill it with people I love. The house I grew up in burned down in an electrical fire in the 2010s, but even if it hadn’t, my parents divorced ten years earlier and have both passed away in recent years, so that sense of home doesn’t exist for me anymore. Beyond that, being Indian American, there is already a sense of unbelonging that is knit into life in the United States.

What do you hope visitors take away after encountering your mural or museum installation in person?

MJ: I just want to offer people passing by a moment of softness. I feel like we have been increasingly deprived of them.

Our Conversation with Baseera Khan:

Your mural, based on Braidrage, uses the act of climbing as a central metaphor. What inspired this gesture, and how did it develop in your work?

Baseera Khan: I was interested in drawing, and using my body as a drawing instrument. I also felt climbing was similar to the choices one makes in drawing, slow methodical movements that create inertia.

Braidrage is a practice of drawing and mark making that helps me navigate and transform intense emotions, specifically rage, through sustained physical and mental exertion. This concept emerged from my personal experience with indoor rock climbing, an activity that unexpectedly became a metaphor for collective self discovery and resilience. The climbing community provided not only physical training but also a supportive environment for confronting and transcending limitations — both literal and metaphorical. It was less about the act of climbing itself and more about cultivating a profound sense of reach and courage within spaces often restricted or inaccessible to uncommon voices.

The braids themselves, integral to this practice, function as multifaceted symbols. Visually, they evoke the imagery of ropes or ladders, serving as conduits for ascent, progress and overcoming obstacles. This visual language evolved within my artistic practice as a powerful means to articulate and document through endurance and mark making, the journey of discovering feminine forms and personal empowerment in my work.

You often speak to your experience as a queer femme Muslim. How do you express the complexity of your identity through your artistic choices?

BK: I approach art making from the perspective of a formally trained contemporary artist with nearly 20 years of experience, rather than explicitly focusing on my sexuality or personality. However, I believe that a creator’s life choices and outlook subliminally influence their artistic expressions. My complex views on life, religion, culture and spirituality often manifest in my work through elements like diagonal splits and materials placed adjacently rather than mixed. Collage, in particular, helps me visualize the ruptures, layers and fragmented perspectives that I navigate, integrating them into both my family life and my identity as an artist. Ultimately, it’s about fostering an expansive understanding of existence at these intersections, and recognizing art’s profound capacity for self definition and collective empathy.

Your Brooklyn Museum show featured a wide range of media. How do you decide which material or format best suits a particular idea?

BK: I am motivated by materials and their identity, where they originate from, their geographies, the economies made from these materials and the process of labor, extraction and distribution that goes into the economies of the materials. Then I ask myself how to make a narrative out of the objects that reveals these complexities.

Many of your works deal with difficult themes like surveillance and displacement. How do you balance urgency with accessibility in your work?

BK: The feeling of surveillance and displacement that we have all felt since the pandemic changed my work deeply. I got more into light, color and form as healing elements, I think about materials that offer protection. I started getting into gardening and keep a botanical corner in my apartment and on my balcony. I make informal drawings from them that then led me to a body of work called Floral Fix and other works from there moving forward. The works are emotional and painterly, they are urgent, so I think I respond to my surroundings and the trajectory of the work shows. Where I was working with patterns and flowers in traditional textiles before, I now take those flowers and create oil paintings that are quite emotional and for me, urgent.

Your own body is often present in your work, either literally or symbolically. What role does embodiment play in your process?

BK: I do use my body as a reference often. I’m interested in psychic spaces and religion in ways that you can never verify what truth is, or what fact is, you can only believe, and alter your state of mind to consume the psychology of what becomes your truth. I think because of this I turn to my body as an archive. I come from a background of ancestors that I am not able to access. I am from many places (African, Arab, South Asian, I also grew up in America), so my lived experience is full of mythologies or collective speculation. The truth that some work is hard to uncover, or for some that are made easily available to them, is a privilege that I have come to understand in the spirit of things. In the psychic space, I find power, in the obfuscation of the archive that I will never know. That’s also why Braidrage became so important to me, or any other performance work became central to the way I understand art and the world.

Since receiving the UOVO Prize, your work has appeared in major exhibitions and public installations. How has your sense of audience shifted during that time?

BK: Last year my gallery closed down and it was a terrifying time for many, not only myself. I think I just get up and work, then work again the next day, but sometimes it’s important to take a step back and celebrate. Receiving the UOVO Prize definitely catapulted my career, but I still have a lot of work to do. And not having representation in New York at this time is interesting; it’s a blessing and a challenge at the same time.

What did it mean to you to place such a personal and charged image on the facade of a building in Brooklyn?

BK: For me it wasn’t personal, it was a collective self. I black out when I’m performing so I can stay focused and not have stage fright. It was an endurance practice.

The materials you use carry strong symbolic weight. How do you source and choose elements like chains, blankets, and hair?

BK: I frequent the Garment District, my mom’s closet and I also use my own hair.

What do you see as the role of public art in today’s political and cultural climate?

BK: Well, let’s hope we get to have public art moving forward. There is a lot of public funding that is being taken away for this type of work. but it’s important, especially if you are a femme person as there are not enough public art works made by female artists.

Melissa Joseph: Tender is on view at Brooklyn Museum through 2 November, 2025.

What are your thoughts?