Charged: Leo Villareal Interview

The light sculptor on his Burning Man origins and how “The Bay Lights” has changed everything

by Michael Slenske

Two decades ago, New York-based light sculptor Leo Villareal attended Burning Man (the annual week-long art event in Black Rock City, Nevada, which culminates around a wooden sculpture of a man set on fire) and the experience changed his life. A few years later Villareal returned to the Nevada desert with a 16-strobe light beacon of his own design, which he fixed to the roof of his group’s RV so that they could find their way home. “I was tired of getting lost, so I made my first piece which was sort of just a utilitarian thing to help me stay oriented. But then I thought, ‘Wow, that’s a very powerful combination: software and light,’” recalls Villareal, who brought the work home to NYC, laid a translucent cover over the top and had just produced his first gallery-worthy light sculpture, “Strobe Matrix.”

Villareal spent the next 10 years broadening the scope of his work with increasingly larger, more technically complicated architectural interventions. Many were commissioned as temporary works, and many have ended up being permanent or semi-permanent. To wit: six years after it was installed, the 41,000 LED, three-years-in-the-making “Multiverse” still envelops the 200 foot-long walkway between the east and west buildings of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. The artist’s “Stars” remains in the windows of the Brooklyn Academy of Music years after it was scheduled for de-installation; the Buckminster Fuller-inspired “Buckyball” that lit up NYC’s Madison Square Park in 2012 is currently being shown outside Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, where it is now part of the institution’s permanent collection. The 25,000 algorithmically-controlled LED lights that make up “The Bay Lights,” which just marked its one-year anniversary, continues to illuminate the night sky across the Bay Area, and may continue to for another decade or so.

The latter—likely the most technologically challenging public art installation ever—is also the subject of a new documentary, “Impossible Light.” The film premiered at SXSW and details the project’s numerous challenges: raising $8 million in private funding over two years, overcoming epic industrial, national security and environmental concerns not to mention finding the right people to get behind the project (from local engineers to public art éminence grise Christo, who wrote letters of endorsement on Villareal’s behalf). On the heels of the film’s premiere and the installation’s anniversary, Villareal checked in from D.—where he was taking some time to absorb the ambient glow of “Multiverse”—to talk about his trajectory from Burner to Bay Area icon, what technology means to his work and what’s next.

If you look back on the strobe light piece you did for Burning Man, could you have ever imagined this kind of trajectory for your work?

Absolutely not. The first year I went to Burning Man was 1994, and I made the strobe piece in ’97. That got me going and then over time I did my first large-scale architectural piece in 2003 at MoMA PS1 in Long Island City, and it just went incrementally from there. But I never thought I’d do anything like “The Bay Lights.” It’s cool what you can do with light.

Were you ever interested in the pioneers of California’s Light and Space movement? Was that something you were thinking about?

I had an art history background, and my family is from Marfa, Texas, so I certainly knew about Donald Judd and Dan Flavin and [James] Turrell. But I studied sculpture and then I got into technology in the early ’90s and I wasn’t quite sure how I was going to fuse all these new tools I was using into my art-making practice. That’s what happened in ’97 [with “Strobe Matrix”], and I realized this is very powerful and this is what I want to pursue. But I would say it was definitely a combination of the Light and Space guys, plus Burning Man, plus technology being in the right place at the right time over and over.

How has your work evolved as technology has advanced?

Certainly I would not be able to do the work I do without LED technology. Solid-state lighting is remarkable in its robustness and in how energy efficient it is. I’m also very involved in creating my own LED circuit boards and control systems and all the software I use is custom-written. I’m working with my programmers—I only go so deep myself—but at the end of the day I’m using the tools that have been custom-made for me, and then I’m very involved in the sequence-making. But I’m all for innovation and I wish it would go faster. I’m really excited for LEDs that last a million hours instead of just 100,000 hours.

What’s your process like when creating public installations?

I’m there to capture that 1% of the time when something exciting happens and I can bring that back—something I’ve harvested—and then I can continue to layer and evolve it. It is a very painterly process, it’s very compositional, very similar to the way you’d compose music. There are certain motifs that repeat at different scales at different tempos. There’s background layers and foreground layers and layers that subtract light, so you’re dealing with negative space.

Since “The Bay Lights” went up on year ago, have you been inundated with projects of that scale?

It’s been unbelievable. We’ve had over half-a-billion media impressions and that was several months ago. The story went from local to national to international and it’s inspired huge amounts of interest in my work and for doing monumental public art. I think what’s exciting is that with “The Bay Lights,” it’s not only a piece of art 50 million people will see in two years, but it’s also good for the city. It’s bringing in, conservatively, $100 million to San Francisco in restaurants and hotels.

Are you involved in the campaign to keep “The Bay Lights” running through 2026?

Yes, we just announced that on 5 March. It’s really about the people of San Francisco. They’ve really fallen in love with the artwork and they want it to remain, which is great. But like I said in the film, this is something that needs to come from the public, not the artist saying, ‘My piece has to be permanent or here for [another] 10 years.’ I just feel honored to have had it up for this long. I’m okay with temporary art; that’s how it is on [Burning Man venue] the Playa, you have to let it come and go. But if something can become iconic and part of the city, of course I’m thrilled to participate in that.

When you walk through cities, do you see the possibilities in the architecture?

Definitely. Over the years my ability to create 3D simulations and visualizations has evolved, which is very important in my work and a lot of projects start like that: showing people what it could look like. That’s how “The Bay Lights” started, with a one-minute animation showing people what it could be.

Is there a new space you’d really love to explore?

I want to get out in nature. There’s some test pieces out in spaces in Texas. Places like Marfa, I think would be very exciting to explore. That’s going in a whole other direction.

Are there any new items on the tech front you’re thinking about the way you might have thought about LEDs years ago?

The control of LEDs used to be very, very expensive. Now you can buy this stuff on a roll from China and, for a couple hundred bucks, you can be sequencing LEDs, which was never possible before. I would like for there to be more really revolutionary innovations in light, but I still think there’s a lot left to do with LED.

What other new projects are you working on at the moment?

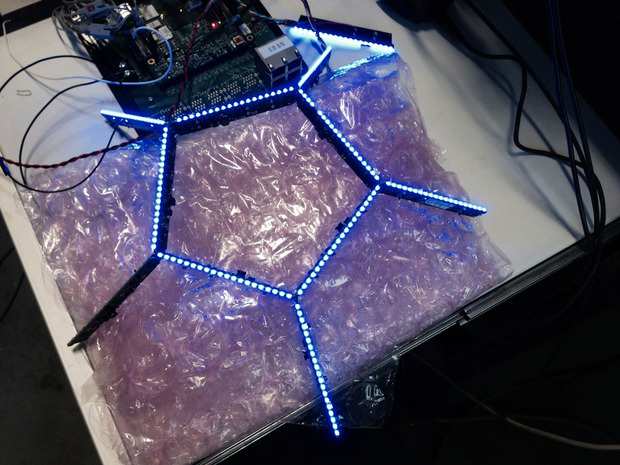

I’ve been focusing more on gallery shows and museums. I’m doing some different group shows, one called “The Light Show,” which is traveling to New Zealand and Australia. I’m currently in the Cartagena Biennial. We’re going to be showing “Buckyball” sometime this year; we’re making a scale model of it.

This is the indoor version of the outdoor work?

Yeah, it’s about a three-foot diameter sphere on the outside and then another sphere within that. I’m all about making smaller pieces and learning at different scales. I’m just really regrouping. Two-and-a-half years working on the Bay Lights was pretty consuming. I just moved studios and have a new studio out in Brooklyn in Industry City. MakerBot is out there.

Is the new studio helping out with the work?

I can think straight with having enough space. I was in the same studio for 15 years in Chelsea, right in the middle of the art world and that was great but it’s just a lot of noise. Going to a place where I can think and work is very important. That’s what the new studio is about. For me it’s really about assessing where I’m at and figuring out the next moves. But it’s definitely an exciting time.

“Buckyball” images courtesy of Leo Villareal Studio, “The Bay Lights” images and “Double Scramble” image courtesy of James Ewing, “Impossible Light” images courtesy of Jeremy Ambers