Interview: Casey Spooner of Fischerspooner

Spanning performance art, music and theatre, the influential New York legend weighs in on his upcoming book “New Truth”

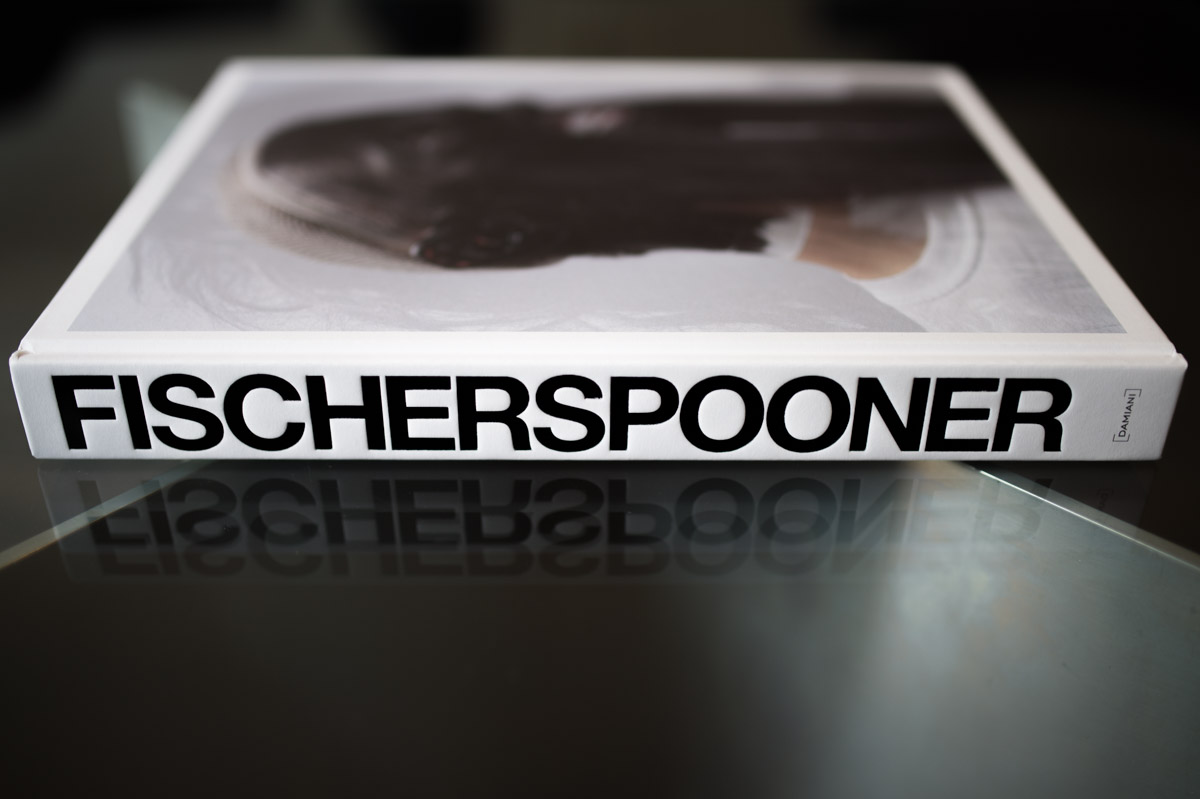

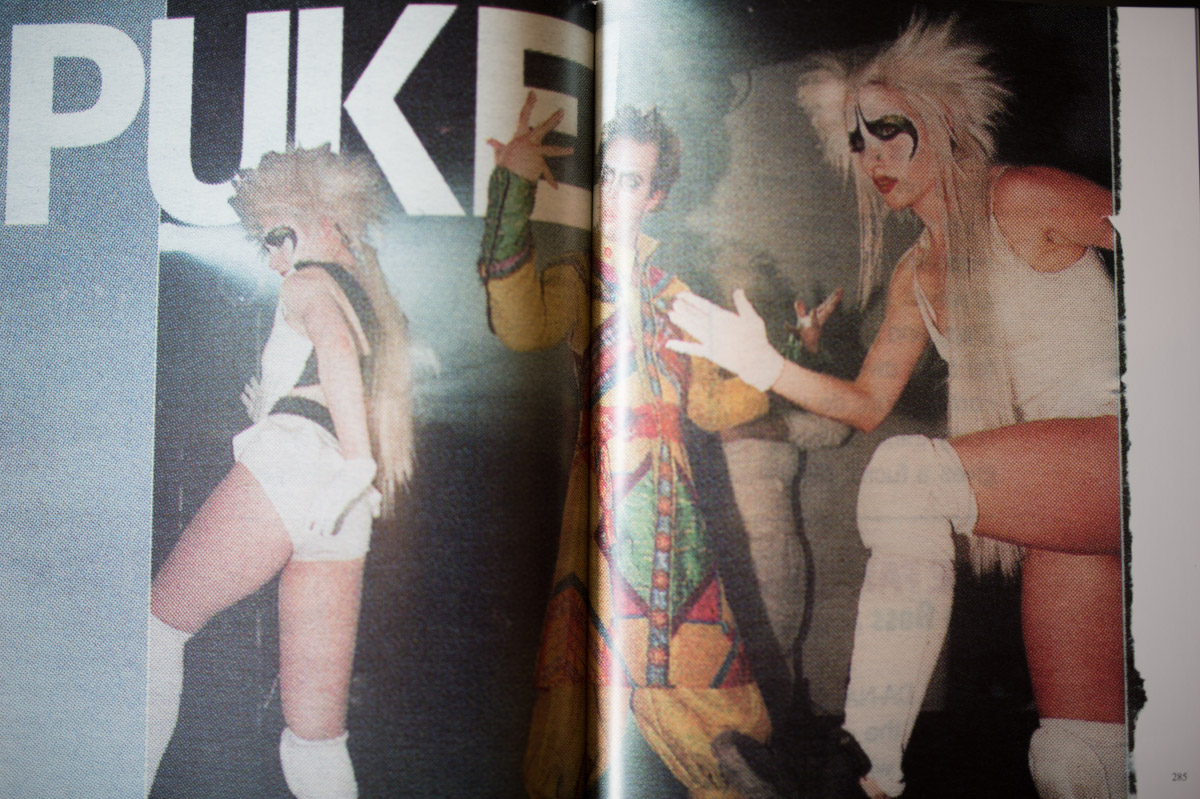

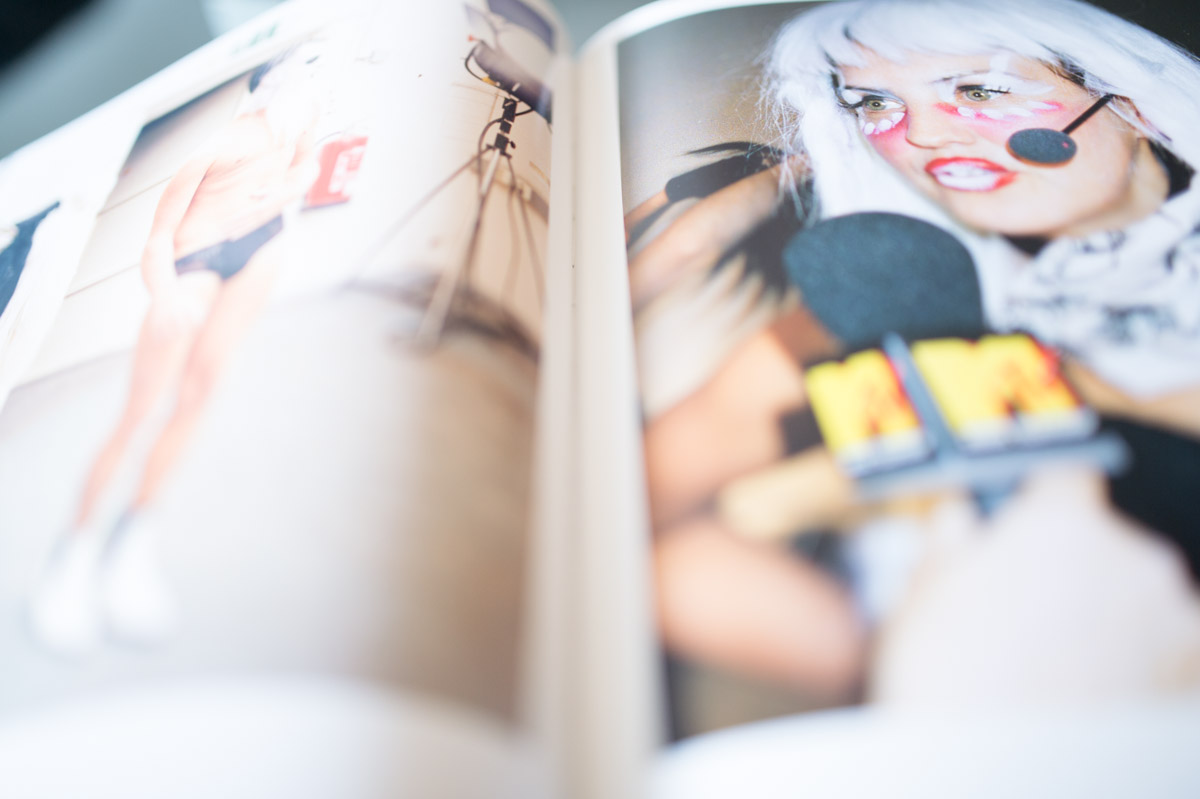

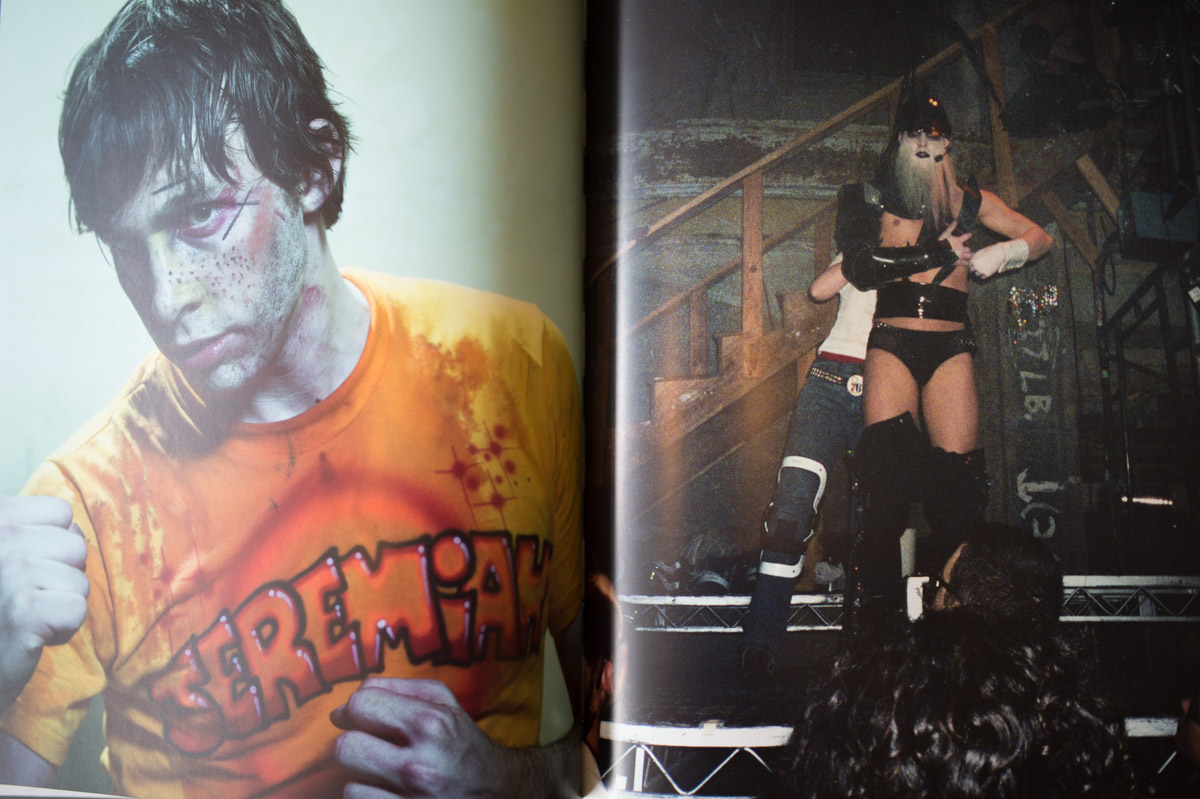

Starbucks isn’t the place New Yorkers go to for art (or really coffee for that matter). However on one fateful night in 1998 at the East Village’s Astor Place location, the coffee retailer was unsuspectingly turned into a guerrilla performance art venue. Casey Spooner and Warren Fischer, art school grads new to the city from Chicago, threw together a performance under the moniker Fischerspooner. From there, the group’s irreverent, over-the-top electronic, art glam—the likes of which had never been done before—took off. Reacting to the grim utilitarian mode of the day, Fischerspooner was a spark of glitter-dusted avant-garde futurism. Now, 16 years later, the band examines their legacy with “New Truth“—a stunning hardcover photography book. We sat down with the crowd-facing half of the genre spanning art project, Casey Spooner, to talk origins, creative process and what’s in the works.

Josh Rubin: The first question I have for you is what came first—music, performance or costumes?

Casey Spooner: In terms of…

JR: In terms of you personally—music, performance or costumes?

CS: My personal creative history? I started as a visual artist. My mom was my art teacher, so I was always making stuff. And I guess she was a very kind of progressive teacher. She didn’t teach you to do things right. She taught you to be open and creative. She was obsessed with this text called “Cybernetic Creativity.” It was some kind of ‘70s progressive [theory].

So that was really where I started. I went to a magnet school for the arts. I did ceramics, I did metalsmith, I did painting, I did printmaking, drawing. Then I guess music stuff started to come into my life. I went to the University of Georgia and I started hanging out with lots of musicians and seeing lots of music, so I got to see incredible and amazing stuff. I toured with some bands as a merch guy, but I made up a weird merchandising idea where I created this thing Performative Merchandising. I would introduce the bands doing weird spoken performance stuff. Then I had a set piece with all the merchandise and I was kind of like a sideshow barker.

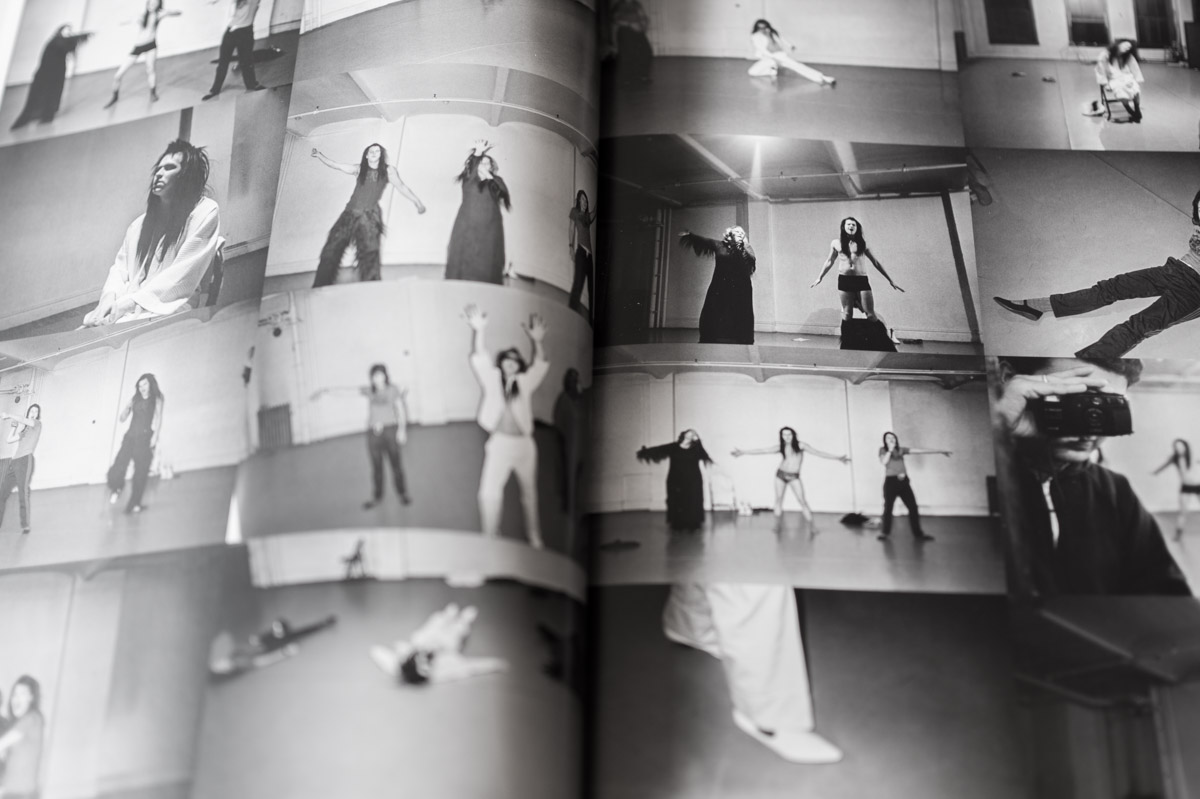

I was like a character with a set piece and a costume, so I guess that’s kind of the beginning. And then in art school, a lot of my painting teachers said that when I talked about my paintings, that was the best part and they thought that I should pursue performing. So I was at the Art Institute of Chicago and it was one of the few schools that had a performance department, so I started studying performance. Then, while I was on tour with one of the bands, they told me about a friend of theirs that had a theater company, called Doorika, and I joined this experimental theater company and worked with them from ’90 to ’99. I co-wrote, helped produce and perform, so it’s always been kind of strange mix of image and performance.

JR: So then with the creation of Fischerspooner was it performance, music, costumes and expression kind of all leaning together into one?

CS: Yeah, I mean you can see in the book it’s very clear. From the get-go there’s a clear intention of doing something that’s visual, sonic and performance. And I mean it starts very modestly, but it’s still self-conscious. And I guess it’s a very strange beginning also to Fischerspooner because it started first as a film project. Warren and I and his wife Karen had worked on a pitch for a TV show that never came to fruition.

JR: What year was that?

CS: This is ’98. Warren, Karen and I made a pitch for this TV show. Warren and Karen were directors at the production company. We shot all this film, we shot for two days. I was working a lot in photography doing sets and props as my day job, and they tapped me to come in, so I oversaw the casting.

The TV pitch didn’t go anywhere. We had all this film footage and Warren was frustrated with his career. He was scared that he was going to be making bad television commercials for the rest of his life—and he had stopped making music. He’s a great musician and he had an amazing band called Table, that I loved. So I said, “Well, we should take the film footage and you should—we should—turn it into something and you should score it. Then you can put that on your reel and then there’s a way you could be working in music and it could be commercial.” We had all this footage we didn’t know what to do with.

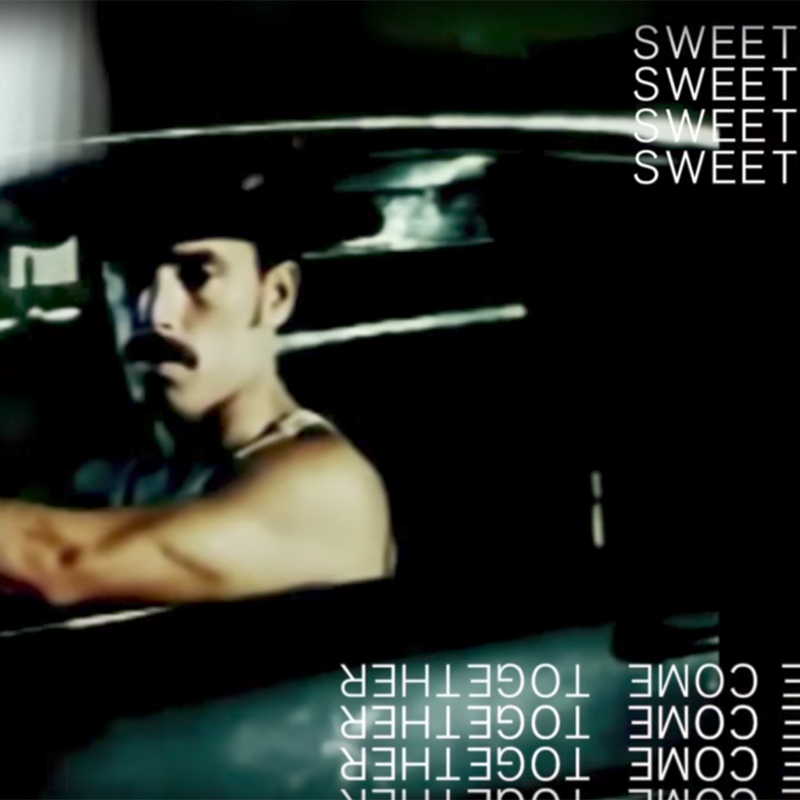

So we started working on a song, then we started working on the soundtrack and the soundtrack turned into a song that was a story that I had been telling about this dirty cab driver trying to pick me up. We ended up making this Bollywood electro song called “Indian Cab Driver.” A friend of mine asked us to perform at this weird variety show in a Starbucks. We did this one-off performance and it was kind of like a bolt of lightning. I had put a lot of time and energy into a lot of projects, and then it was sort of the one that I least expected was this strange, magical combination of: A) Doing something super creative in a super commercial environment; B) It was an environment that wasn’t a performance space, it wasn’t a public space. It was a private space thought of as public.

It wasn’t the best song and I wouldn’t say it was the most stellar performance, but you could tell it was the foundation for a big idea.

All of the sudden, it was like the environment, the context was super-bizarre and awesome and brought up all these weird issues about art and commerce. Because I had been working in experimental theater so long, I was a real seasoned performer and I could kind of do anything anywhere, so I was able to do this kind of strange, guerrilla, pop performance in this unlikely location. It wasn’t the best song and I wouldn’t say it was the most stellar performance, but you could tell it was the foundation for a big idea. One of the other elements was that we integrated some external theater tropes and we built in a mistake into the first song in the first 30 seconds. The first time we performed the first song, it was a real mistake, so I performed the stage mistake in the middle of a real one, so all the sudden now we knew what was accidental and what was intentional.

It created this complete theatrical device that was the foundation for years. The second show I was dressed like that crazy monster in an all human hair suit, completely covered, painted black and stripped down to red panties. There was always pretty music and images and it was music, images and performance immediately. Then it just developed more and more.

JR: When we were emailing for this interview and I was asking you to take a picture, you said, “I’m very very particular about photography,” but you also said, “Reality is not my thing.”

CS: I’m not interested in, I don’t know—I like heightened images, so you know, I’m just horrified. I’ve had too many experiences where somebody shows up and tries to take a picture of you for an interview and it’s just not a powerful idea. If I’m going to make an image—and it sounds so stupid, but my image is kind of my work, so if I don’t, and I’ve tried to control it for a long time and then I let go because I got pressure from every side to make myself available. And it didn’t work. You just end up with a lot of terrible pictures, so I don’t know, I’d just rather deliver fewer, better, great things.

JR: The moment where you decided to let go, is that where the song came from or…

CS: Oh God, no. When you start to get involved with a major label, doing major label releases, or doing a press tour and you’re in a different city every day, you can’t—the only way to supply the demand is just pump out tons of—you see pictures of people and you’re like, “God, I can’t believe they actually let that run.” Anyway, I’m in a new time, it’s kind of like the beginning of a new chapter. I’m at least starting with the intention of, I need to start with a strong image.

JR: Of course. The next question you’ve kind of already answered, but the comment was that your performances are incredibly photogenic. Is that part of the plan?

CS: Yes. It’s obviously related to my interests in art history and painting. I always feel that I’m making a picture when I’m making a performance. But it’s a picture that needs to move, and change, and evolve in real time, but I don’t know if I’m necessarily building it for photography, it just lends itself to photography.

It’s actually really funny because there’s a description in the book from the editor and she talks about the way I’m performing on Top of the Pops. And it’s the first time I’ve ever performed on television. No one told me how to perform on television. I mean you’re raised on TV, you think you know. Everyone imagines themselves on television, so you think, “Oh, when I’m in that situation, I’ll know exactly what to do.” But it’s a completely different system and so I had done plenty of photography and plenty of work on stage, but I had never done television. I just did not understand what was gonna happen. So ironically, I’d been so used to working in the art world and having control over—and I say control, it’s not like some tyrannical thing, it’s just that if I wanted to do something twice, we could. If I wanted to do it fast, or slow, I could just do whatever I needed to do.

So doing a TV show, I thought that it was more like theater. It wasn’t. When we started, the music was too low and I couldn’t really hear it. So I thought, “You know what? It’s no big deal, I’ll just mark through this. Then we’ll know the protocol and then we’ll go through and we’ll redo it.” When we finished that first performance, I wasn’t even working that hard, I was just kind of marking it. When we finished, a disembodied voice from some control room said, “OK, thank you very much.” I was like, “No, no, that was just a walk-through,” and they’re like, “No, no, you’re done.” So there’s a description in the book that’s really funny because it talks about how the way I’m performing is as if I am continuously posing for a photograph.

JR: You talked a little about working with Warren and I’ve seen the book. It’s very much you two side by side in terms of dialogue and talking about the moments. On stage, it’s you. Can you talk about that, the creative relationship versus the one that is kind of behind the scenes. It’s obviously an integral part.

CS: Yeah, he likes it that way. He regrets that he ever posed for a photograph. He wishes that he’d never—he doesn’t want to be part of the image. I’m a performer, he’s not, but especially in these early years, these early performances, he was always behind the soundboard. So it was really like we were in dialogue on stage. And because the show was entirely, you know, track—it was all prerecorded music—so he had total control over when things happened and when they didn’t. When they would stop and when they would start.

So we would have this kind of strange conversation that would happen in front of an audience. The project is really about the relationship between Warren and me. I think that he pushes me in certain ways and I push him in other ways. I think that I wouldn’t do certain things that he triggers me to do and vice versa, so we kind of have this dialogue, which can be incredibly frustrating sometimes, but we find compromise.

JR: The book is, as you said, meant to document the early days. Is it for your fans or is it for a new audience? It is an art piece on its own—people can get a lot from this without ever seeing you perform or hearing your music.

CS: Yeah, I mean that wasn’t a concern. I wanted to make something that would be of interest to someone who didn’t know anything. I think that it does that. I think that it gives context to what you’re seeing. There was always a concern to make it clear, to give things context, to tell a story.

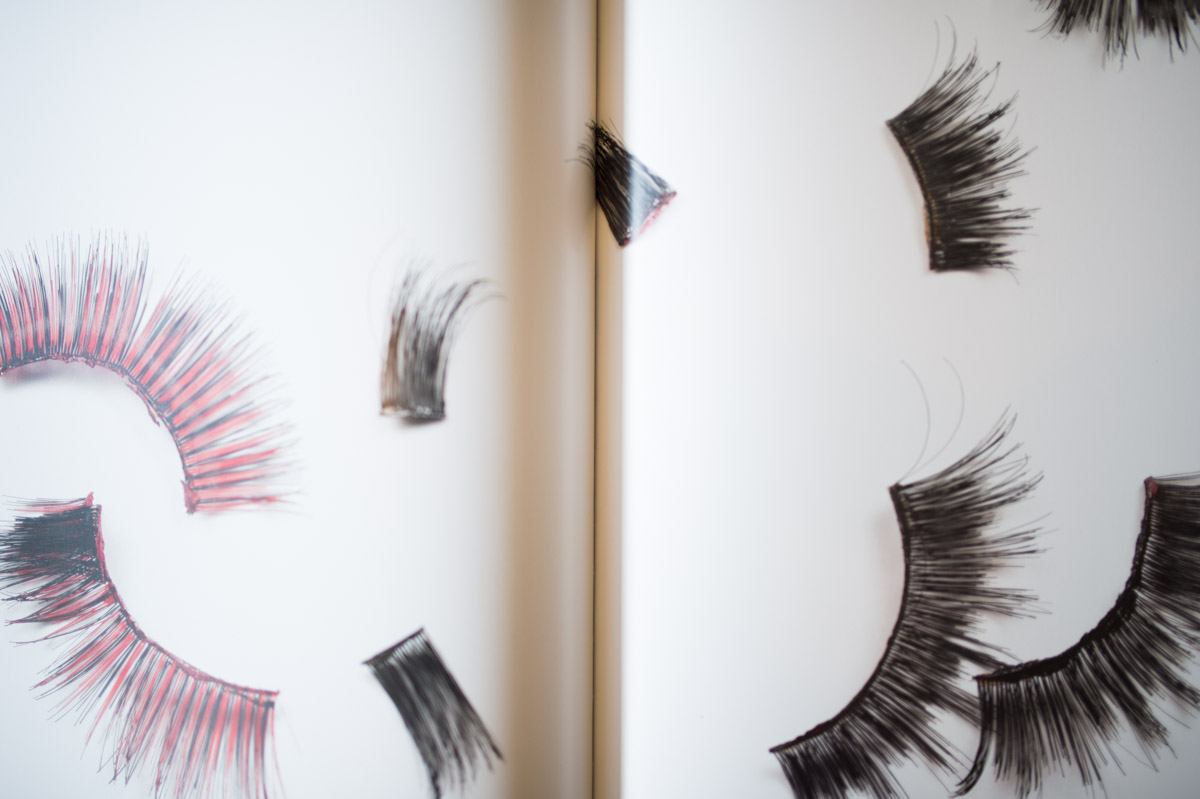

It was really difficult, because we didn’t know how we were going to structure the book for a long time, and there is an incredible amount of material. This book is 336 pages and we pushed it as far as we could. We added an extra 70 pages to it in the process because when we started editing the book, we went through a period where we just found all the material, prepared it, started laying it out and I’d say there was a phase that I call, “making pages” and I was just making as many pages as I could.

Once we felt like we had covered all the material, we started editing pages and I’d say we had about 500 pages. We had to cut down. Originally we were supposed to cut to 256 and then when we got to 320. At four o’clock in the morning, the book started to fall apart.

JR: How long was the process?

CS: I got the idea to make the book in I’d say 2006, but we didn’t stop working. I went consistently from ’98 to 2006. I just didn’t get any time off. We had a storage space and stuff would just get thrown in the storage space and it was an absolute disaster. I mean nothing was organized. You couldn’t even get in, it was just piles of shit.

I would open a box and it would be piles of test Polaroids, or forgotten photoshoots, or unused material or stuff that was only seen one time.

I finally had some time off and I went in to try to organize everything. As I went through, it was crazy the amount of things that I was finding that I had forgotten about. I would open a box and it would be piles of test Polaroids, or forgotten photoshoots, or unused material or stuff that was only seen one time. So that was when I was like, “You know what, we really should make a book.” Then I spent about two years dealing with just photography and printed matter. I worked with an intern once a week for two years and we scanned and created a digital archive that didn’t even begin to cover everything, but it was something. Then we were in negotiations to find a publisher for a while. Then there’s kind of some prep done, but the gun fired for the sprint in January.

JR: This year [2014]?

CS: Yeah, we started working January 15th and it was like all of a sudden, seven years of thinking about it and prepping for it quietly. It was kind of like, “OK time to go.” Then, within two weeks, I had to come up with the cover, the synopsis, a bio, sample pages. We needed to start sourcing material from other contributors because people had stuff all over the place.

Also, the thing that’s interesting is that it’s kind of the end of analog into digital and that’s another good part of the story that happens to us. We’re working analog ’98, ’99. I mean there’s the beginnings of the digital revolution happening. We start working in synth software that wasn’t available before. Typically electronic music had been made on outboard analog keyboards and stuff was always being done on laptops. Mac all a sudden revolutionized the home computer and at the same time I had a computer for the first time and became, basically, a producer: managing and organizing the project internationally. We were dealing with all these people all around the world. It was just me and my orange iMac.

It was something that was very local and very downtown, very New York that all a sudden became international really fast.

The big thing is that we had this window of time where people didn’t have cellphones yet. People weren’t really online yet. It was growing, and so we built the idea and created lots of images and kind of honed our concept. Then the internet exploded and it just took all that material and disseminated it around the world immediately and created demand that hadn’t been there before. It was something that was very local and very downtown, very New York that all a sudden became international really fast. Then the music just took off without any kind of plan. It was absorbed and you kind of see the boom in Napster parallels the interest in the project. And there was such a wealth of stuff for people to see that there was always—there was enough to hold people’s interest.

JR: Why “New Truth?”

CS: I feel like—goddamn this is a good question. It was a quote that was in one of our early artist statements, and it was talking about reflecting the times and showing kind of what the new experience was. How it wasn’t realism, and it was naturalism. It’s a reflection of this new era that we entered into and this is just the beginning of that. So this idea of image and communication, but also something that was really grounded in these performances that were very alive. They weren’t mediated and they weren’t plastic. They were very raw, so one of the things I had a hard time with about making the book is that I’m really not a fan of nostalgia. I didn’t like to look back. I always try to go forward.

JR: Then why did all the costumes and props go to storage?

CS: I knew to keep stuff. I knew to keep everything. I always knew it was gonna be important to keep things. I don’t know why, not simply in terms of keeping things, but in terms of thinking about things. I don’t like to think back. I mean obviously you learn from your experiences, but I don’t like to pine over some sort of utopic past. And it was something that really irritated me a lot about early feedback about the project is that they would talk about how it was a nostalgia act and it was all about the ‘80s, which I get, you know. At the time, there was no one being flamboyant or wearing costumes or wigs or makeup or any of that stuff. So that seemed to harken back to this lost sort of glamor of the ‘80s, but to me it was so much about the present because really the initial impulse came out of this kind of Y2K paranoia.

I felt like I was living in New York in this very dark and paranoid time and creatively the world was very monochromatic. It was like everything in fashion was super utilitarian. Everything had this kind of sterile, fake ‘60s futurism to it, so everyone was bracing for eminent disaster with rumors of the city buying, 60,000 body bags and people stocking up on water—people making plans for complete chaos and every microchip and every possible thing no longer functioning: every elevator, every escalator, every stoplight—the world is going to be thrown into complete and utter chaos.

What do I want to be doing at the stroke of midnight 1999? I want to be celebrating, I want to be colorful, I want to be dancing, I want to be like covered in sweat, glitter and a jockstrap.

I was reacting to that, this project was a reaction to that fear. So I decided, if this is all going to like collapse, what do I want to do? What do I want to be doing at the stroke of midnight 1999? I want to be celebrating, I want to be colorful, I want to be dancing, I want to be like covered in sweat, glitter and a jockstrap. I want to be as alive as I can possibly be. That was the genesis for all this strange, crazy, flamboyance that was not about recreating some lost past. It was about embracing the present.

JR: Is there anything we haven’t talk about related to this project that you want to talk about?

CS: No. I guess I haven’t really done an interview in a while so I just really gave it to you. Oh, we’re making a new record, we’re about 11 songs in. I’ve done kind of all the writing and now Warren is going in on the production.

JR: Is that usually the sequence?

CS: No, this is a little bit different, this process. It used to be that we would go to the studio, we would go together. I didn’t know anything about how to make music and I didn’t care. So I’m working more the way I did as a director in experimental theater, where I just show up to rehearsal and do stuff, and then the director responds to whatever it is I’m doing and that is the way we go. That process fell away over time and slowly I learned more about how to write. It used to be kind of difficult because Warren would sort of fever over the music for months and when I would get music, it would be almost finished. It would be like 90% finished and it would be so full of musical ideas that there was hardly anywhere to put a vocal.

Sometimes, I would have to copy melodic parts in order to just get in the song because there was nowhere for me to fit. Now we’ve done kind of the opposite where he’s given me these very minimal tracks and and then I write all the melody and all the lyrics and just fill them up, chock full of ideas. He’ll build around that, so it’s kind of gone exactly the opposite. Then I guess that’s it, trying to finish that and have something out when the book releases on 31 October.

JR: You move quickly.

CS: Just a song, not the whole record. No, I can’t get the whole record out. I mean it’s all there, it could go. I think we could’ve had most of the record done by 1 November. Now I have to sweat over the image and how to present it. I just feel like I’ve done every iteration of an avant pop show.

JR: The image for the album art or for the show …

CS: Both, that’s all one thing. It all grows out of the same place, so that’s kind of what I’m listening for. Then I’m also doing more creative direction for other people, which has been fun. I’ve been doing more photography. I just shot a portrait of Laverne Cox for the September issue of V magazine. Then I’m working on a couple other kind of big, crazy, creative direction jobs, which is nice because sometimes when it’s your own thing, I get mired in it. You know how it’s always easier to help somebody else? It’s the same way with creative direction, like I can just see what the problem is and I can tell everybody exactly how to fix it.

“New Truth” is set to release 31 October and is currently available for pre-order

for $35.

Portrait by Yuki James, book images by Josh Rubin