Interview: Multimedia Artist Cey Adams

From NYC graffiti to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, and beyond

Cey Adams’ bust in the pantheon of New York artists is well-cemented. Queens-born Adams grew up writing graffiti with the likes of Lee Quiñones, Futura, and Haze; and taking part in downtown’s scene, exhibiting alongside Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. After creating logos and designs for friends like the Beastie Boys, Adams was soon tapped by Russell Simmons to become Creative Director at Def Jam Records, where he art directed album covers like Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready To Die, Public Enemy’s Fear Of a Black Planet and many more. From exhibiting and teaching at places like MoMA, Brooklyn Museum, Stamford, it’s been an enviable career—and one that has recently seen a slate of projects firmly founded in the past while still looking toward the future.

His latest book, The Mash Up: Hip-Hop Photos Remixed by Iconic Graffiti Artists, does exactly that. Handpicking photos from British photographer Janette Beckman’s dense archive, Adams recruited artists to lend their touch to one of 30 of her stills. His Trusted Brands series of collages reimagines logos from beloved childhood brands—layering beautiful details in their construction. Then he was tapped by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture to create a mural-sized mixed media American Flag (which he did, live, in the National Mall) called One Nation, to honor heroes of the civil rights movement.

His superb collage work led Pabst Blue Ribbon to commission Adams to design limited edition cans and packaging for each of their brews, using much of the techniques born in his Trusted Brands series. The brand is now working with Adams to launch National Mural Day ( 7 May), in order to celebrate not only the early work of graffiti writers, but all mural artists who labor to make our cities more aesthetically rich.

We spoke with Adams about his early graffiti years, working with Def Jam, and everything from The Mash Up book to the One Nation mural and curating National Mural Day.

You said the ’80s was your favorite time. Let’s start at the beginning. Tell us about growing up with guys like Futura, Lee Quiñones, Haze, etc—what was it like at that time? Because, obviously, nobody knew that graffiti and hip-hop would take over the world.

What I remember the most is that it was a sense of community. I mean, we were all trying to get to where we were going and nobody sort of knew where that was. It was really just trying to establish ourselves as artists. We were all really young. Without comparing it to now, it was just this idea that we were very serious about what we were doing from very early on.

It’s interesting you say you were so serious—did anybody think writing graffiti or breakdancing or playing records would turn into something that you could make $250 million a year?

When I say “serious,” I mean versus all the other people that stopped. You think about the ’80s, there were thousands and thousands of people that were graffiti artists, thousands of people that were breakdancers, thousands of people that want to be MCs. Futura stayed the course, I stayed the course, Lee stayed the course. When I’m saying that, I’m sort of referring to the people that knew who they were. You look at that core group that I came up with back then—DAZE, Crash, Pink, Haze, Doze Green—they’re all still professional artists. It’s a big deal.

Then you were recruited by Russell Simmons. What was that like—being in that energy of early hip-hop and seeing these guys that were your friends blow up and start playing arenas, touring worldwide?

It was a simpler time. I mean, it wasn’t like you felt anything was happening. It was moving slow. If there was just club date, I designed a flyer… It was a little while later when we started silk-screening T-shirts. Everything that the Beastie Boys wore, I made by hand. If you look at those early photographs where they have baseball caps on and it says Beastie Boys, I made it by hand, and I only made enough for the guys in the band.

Then things started to change for me, because when License to Ill happened, all of a sudden I’m designing and things are being turned around instantly. I got five or six T-shirt designs in the marketplace, and I have tour backdrops. My artwork is on posters and flyers and that’s when the lightbulb moment happened, and all of a sudden, it was this whirlwind of all these great things happening. Also, it was when I started my company, Drawing Board Graphic Design, and I started designing for other bands as well: Run-DMC, Hoodini, Kurtis Blow, De La Soul, Slick Rick.

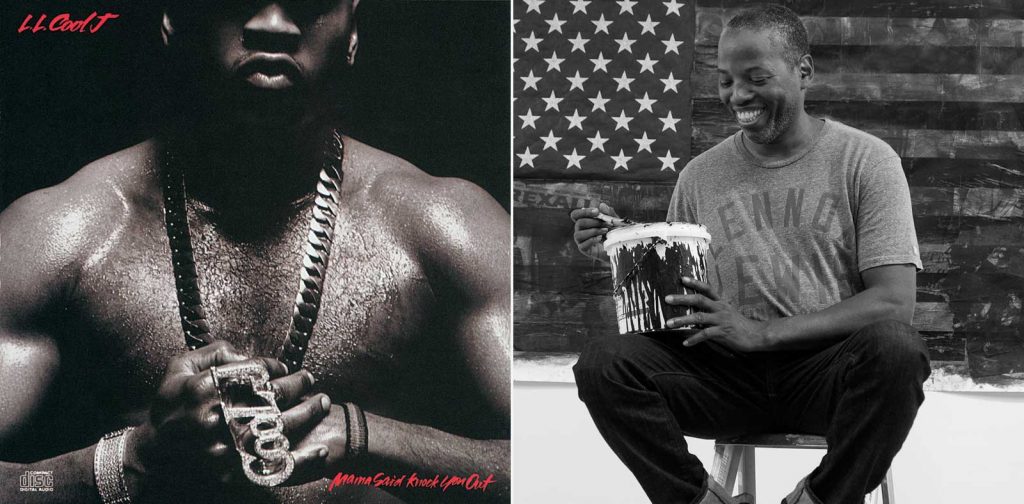

Let’s talk about some of your most recognizable work, like Mamma Said Knock You Out. Even though LL is an icon, that’s probably his most famous album cover.

I would think so. I always said Mamma Said Knock You Out has a special place in my heart because it was the first time I think we got to work with a really amazing photographer. We got to create an album cover in black and white and just let the photography speak for itself. And also, it was LL’s third record—I think he was open to being a little bit more creative.

What was your involvement? Did you write the script, did you have creative input on how the picture was taken?

No, no, no. There’s so much more to it than that. I was art directing and designing the record along with my partner Steve Carr, and LL was very involved, and as a matter of fact he’d come from a photo shoot for Italian Vogue I think, and the photographer gave him a couple of work prints. And he came into the offices and said, “This is what I want the cover to be,” and he showed us the photography. And there was just this beautiful black and white graphic and his face was obscured and at the time, being able to do a conceptual album cover like that was unheard of.

So immediately we jumped at the chance to get to do something really powerful and have the focus be about high art and not the stereotypical image of a guy standing in front of a brick wall with a mean mug on. And Momma Said Knock You Out was that breakout record for all of us.

Your Trusted Brands series is super-interesting, but surely some people would look at those and say, “It’s just a logo.”

You know, that’s part of the other side of it. I wouldn’t call it a problem but the thing is, people are so familiar with what they’re looking at they sort of also dismiss it because they can’t see the detail in the work when they’re looking at it online. The thing that I’m really concerned about is making sure that people understand that when you’re looking at something that is familiar, I also want the viewer to sort of take a much closer look. Especially when you’re looking at things online, because your eye just sort of glosses over it because it’s familiar.

It’s not the same as if you saw that painting in a museum or a gallery and you’re there to observe every inch of it, and you’re like, “Oh, I get it.” Coke. Pepsi. Pabst Blue Ribbon. Whatever it is, you’re sort of dismissing how much is involved in the decision making. I mean for the Pabst can design project I went into their archives and spent days making decisions about their old advertising and how to incorporate that into this graphic design, but when you take it across the room, you move it three or four feet back all you see is the Pabst Blue Ribbon logo. Which is okay, but for me this is also a piece of handmade art that took me days to make. It’s not just a Xerox of the logo.

And it’s all handmade?

The whole thing is done by hand. I took a lot of their advertisements and I photocopied them to give it a lot of grain and texture and then I tore them up, I hand-tinted them, and then I started to weave them into the design. You have to see this much, much larger because it’s really hard to see all of the detail. There’s so many things that you just can’t pick up. But the goal is to create something that, to the viewer, looks familiar, but then when you push in you see all of this detail and all this intricate storytelling that you might miss if you’re looking at it on a digital device that’s the size of the palm of your hand.

Can you tell us a little about The Mash Up: Hip-Hop Photos Remixed by Iconic Graffiti Artists book?

The idea behind The Mash Up is really a way of honoring my graffiti and street art friends and giving them an opportunity to work on top of Janette Beckman’s legendary photography of hip-hop artists. And so for me, it’s sort of coming full-circle because I came up with all of those folks back in the day, and then I worked with all the recording artists. And now we sort of can step back and look at the body of work that we’ve created for ourselves and it’s really just a sort of full-circle moment where all these things in my life are coming together in this point in time through the art that I’m making.

It’s interesting because not only is it a mash-up of different people, but it’s also a mash-up of genres. Janette’s photography, the subjects are musical artists, the drawings on top are graphic art—it seems to really reflect your life.

And art and music go hand-in-hand, and that’s why I was saying: for me it’s a full-circle moment because I’ve worked with the recording artists that are in the images and now we’re working on top of those images and putting it in a context of turning it into art. And the ’80s and ’90s are back in a big way and everybody’s nostalgic for that early period, and it’s just a lot of fun to introduce new people to the work that I made in some cases 20, 30 years ago.

We were all young and hanging out downtown trying to find our voice

It’s noteworthy that you selected Keith Haring as the subject of your piece. Legendarily, you came up with him, Basquiat and Warhol, right? Can you tell me a little bit about your time with them and their influence?

You know, Keith and Jean-Michel were a part of a much larger group, and they tend to get a lot of the attention, but Rammellzee was part of that group. Dondi was part of that group. Frosty Freeze was part of that group. We were all young and hanging out downtown trying to find our voice, and I think they did something that was very special, but there are so many other people that have done work that’s special as well that don’t get the recognition.

Who do you feel should get more attention?

Certainly somebody like Jester, who’s in the book. He’s a pioneer who created the bubble letter style and made that popular. And that’s the thing about hip-hop is that you have a couple of these people that break out, and then they sort of get so much attention that overshadows all these other talented people.

I was thinking about that recently because at the Annenberg [Space For Photography’s Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop exhibit] they have a video of Great Day Out where it’s the photograph that Gordon Parks took of all of the hip-hop artists back in the day in Harlem. You have Mos Def there like fiending over seeing Slick Rick wearing all of his truck jewelry—he’s so happy just to witness that with his own two eyes. And then you have Questlove talking about how excited he is to be there. And now both those guys are icons. It’s fun to look back at a time when their careers hadn’t taken off yet… they were just fans. The same thing happens with graffiti and street art. You have all these amazing artists that have just done so much great work over the years but for whatever reason they don’t get the recognition that they deserve. Phase 2 is one of those artists. He’s the guy who pioneered hip-hop club flyers, back in the ’70s along with Buddy Esquire. But his name doesn’t get mentioned alongside all the greats. And it should because he’s one of the most important pioneers.

How did the One Nation mural project come around?

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture reached out to me to do a project for the inaugural dedication of the museum. And the dedication was done by President Barack Obama at the time. So when they approached me about making a piece of art, I jumped at the chance to do something on the National Mall. I mean, wow. So my idea was: I wanted to create a giant American flag, but I made it a black American flag as a way of taking the focus off of the red, white and blue, and putting it back on civil rights leaders and cultural pioneers that it helped to shape this country.

How tough was doing it live?

It was very difficult. I had to get around the logistics of dealing with the Secret Service and all kinds of things. And just the obstacles of painting outside. If I needed another piece of material, or some artwork or something, I had to make do with whatever I had there, because I couldn’t leave the site. It was just a logistical nightmare. And so I had to work on the fly, and basically create something that I was happy with. And there’s just no room for error really. But the thing that was the most fun to me is that I was making a live piece of artwork in front of an audience that was actively involved in the participation, because we’re all sharing in this historic event…

That whole moment was so powerful. It’s hard to even recall what it felt like because I was exhausted from working sun-up to sun-down every day. And every day, I would get up and I would go right back to the site. Sheer joy pushed me to finish the piece.

How did you get approached to doing National Mural Day?

National Mural Day was something that the folks at Pabst Blue Ribbon wanted to shine a light on, as a way of acknowledging all of the talented people that are out there making art every day. Really it’s just a sharing opportunity. It’s a moment for people to come together and celebrate art. My hope is that National Mural Day will be a day to focus on celebrating creative talent. Even beyond just the idea of murals is the idea of public art, and letting people know that it’s their responsibility to support public art. It reminds people that we’re here, we exist, and what we’re doing is important.

That’s precisely the world you came from, too.

Exactly. Another full-circle moment. Having this opportunity where a brand like Pabst Blue Ribbon is celebrating the history and the culture in this way, and lending support to it is really great. And that’s not something that I take lightly because, for me, it’s great to be recognized in that way. And it’s also great to have them support the work that I’m doing as an individual.

What was your role?

My job was to point them in the direction of talented artists that I think need to have a light shine on them. And so I tapped a woman named Sophia Dawson. Another artist named André Trenier, Andrea Von Bujdoss and Queen Andrea. It was really just to let them know these are people that are representative of a much larger collective of creative talent, because they’re out there making work that matters and makes a difference.

Are you doing a mural as well?

I am making a mural in New York City on 7 May in Williamsburg. It’s going to be pretty big, and I’m going to be out there all day long, just meeting and saying thank you to the people that have been supporting my work from the very beginning.

Images courtesy of Cey Adams