This is NPR: The First Forty Years

An interview with National Public Radio correspondent Ari Shapiro about the station’s new book

Both beautifully designed and infinitely interesting, “This is NPR: The First Forty Years” chronicles the first 40 years of National Public Radio. Correspondents who have been—and many who still are—in the thick of it all, including Cokie Roberts, Susan Stamberg, Noah Adams, John Ydstie, Renée Montagne, Ari Shapiro and David Folkeflick, each cover one chapter of the book. Going decade by decade, the cast of reporters provide compellingly lucid insight on NPR’s own history and evolution, recounting some of the most important historical events of our time. The 256-page book also includes a bonus CD with six classic NPR broadcasts dating back to the 1971 May Day demonstrations in Washington D.C. against the Vietnam War.

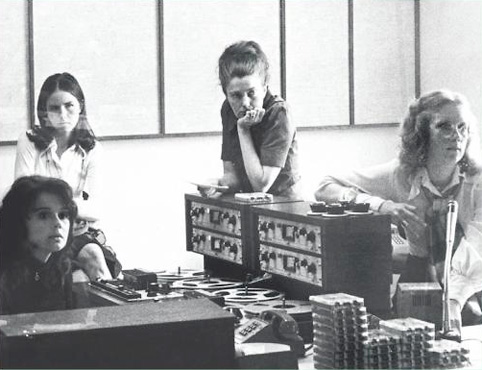

“This is NPR” fits perfectly on bookshelves of diehard NPR fans and casual listeners alike. With photographs of behind-the-scenes action, anecdotes, original reporting and contributions by a “who’s who” of staff and correspondents, the book provides an intimate look into a world many of us only experience on an audible level. The birth of now-famous programs, the woes of funding and budget crises and the internal culture that connects NPR so strongly with its 27 million listeners is on full display—right alongside the world events that shaped the past four decades. The D.C.-based design firm Design Army added an exceptional level of aesthetic value to an already-rich text through beautiful typography and smart infographics, handling a treasure trove of archival photography and physical production values that make the book a truly special experience.

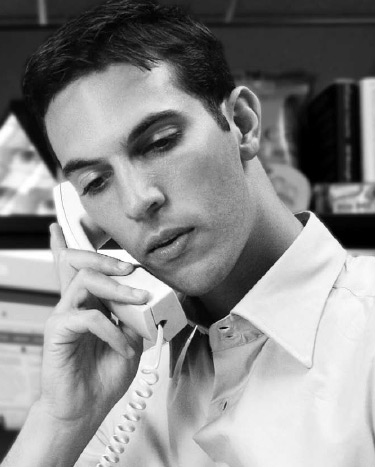

We had the chance to talk with NPR’s White House Correspondent, Ari Shapiro, who wrote the chapter about the most recent decade. Shapiro, the youngest NPR employee to become a correspondent (he was 27 at the time), offered his thoughts on what makes the organization unique and how NPR lives by its mantra of “Always put the listener first.”

One of our favorite parts of the book is to see NPR’s content—something so based in the act of listening—come alive visually. What’s your favorite part of the book?

Having lived through the last ten years of NPR’s history, being able to look at and learn everything that came before me is really fun. If I had to choose a specific part though, on page 58 there is a memo called “a name for the morning program” and there are options for what they should call this show we all now know as Morning Edition.

The possibilities include: “Daybreak,” “Starting Line,” “At First Glance” and so on. I think my favorite is “Earth Rise.” It’s just sort of amazing to think of this program that now has roughly 13 million listeners per week that could have potentially been called “Earth Rise.” It underscores what a scrappy, fledgling sort of boot straps project this was—not very long ago.

It’s not uncommon to hear NPR fans describe themselves as “NPR Junkies.” What do you think makes NPR so special to its listeners?

I think people who devotedly watch CNN or MSNBC or Fox news don’t necessarily identify with those news organizations in the way that people identify with NPR. I think there’s something about the intimacy of the medium of radio. I also think that NPR has never talked down to its listeners, and sometimes that can turn into a cliché of NPR being “elitist” but I don’t think we are. I think we just talk to people like grownups, and there are not many places left in broadcast journalism where that’s happening. I think people respect and appreciate that.

One element to radio is that it engages our imagination, and the book serves as a really great supplement to that. Finding out what people look like, not only now, but thirty years ago is really engaging on an exploratory level.

On the back cover of the book there is a quote from Cokie Roberts that reads, “A picture is not, in fact, worth a thousand words. As Susan Stamberg is fond of saying, “Radio has the best pictures.” There is something about hearing stories from Afghanistan, or the Amazon, or Detroit where the intimacy of the person’s voice and the sound of the place a person is reporting from engages you in a way that just having everything handed to you on a plate, doesn’t. When you see somebody, you jump to all kinds of instant conclusions about who they are and whether you relate to them or not. When you just hear somebody’s voice, it’s much easier to relate to them even if they are a person, who, if you saw them on the street, you may walk to the other side of the street.

But it is fun to look through this book, even for me who works with and knows these people, to look at pictures of them from thirty years ago putting on a show with, essentially, spit and scotch tape.

In the creation of this book and through writing your chapter, were there things that you learned or came across that may have reaffirmed your belief in NPR?

Working at NPR is a constant discovery and reaffirmation that the place and the people are just as inquisitive, friendly, collegial, thoughtful, creative and well-intentioned as you would hope they would be from listening to them on the radio—it’s just amazing to have these people as colleagues.

One of the things I most enjoyed about writing the chapter in the book is that, because it covered a time that I was at NPR, I was able to go to the people whose stories I had heard through the grapevine and hear it from them directly. For instance, I had always heard how Lourdes Garcia-Navarro’s Toughbook computer had taken a bullet and survived when she was driving from the Baghdad airport into the city. And I went to Lourdes and I said “tell me the story.” And then I went to the head of our foreign desk, Loren Jenkins, and he told me about buying the armored car Lourdes was riding in for $100,000 from Mexico City and having it shipped to Baghdad right before this event where it came under fire. I got to talk with Adam Davidson of Planet Money about how that took shape and Bob Boilen of NPR Music about how that was created. Writing this chapter allowed me to explore this place that I am now at the center of every day in a way that I had not before.

That collegiality and respect among staff you mention really comes across on the air as it does in the book.

We could all be making more money doing what we do somewhere else. Everybody that works at NPR works here because they want to be at NPR. Nobody is here for the money. And one of the best things about NPR is the audience. The fact that there is there is this large, dedicated group of thoughtful and creative people who are hungry for knowledge and feel passionately about what we’re doing and what we’re putting on the radio is constant daily encouragement.

So, we’ve now seen the last forty years—what’s next?

Just recently NPR created an investigative unit which reflects a desire to move even further into the investigative news reporting realm than where we are now. We feel an obligation to step in and fill the gap left by other news organizations laying people off, closing foreign bureaus and doing less investigative work than they had done before.

As far as our delivery, it used to be that people could only listen to us on the radio, and yes, radio may be declining—thankfully not ours—but audio is more popular than ever. Lots and lots of people are walking around with earbuds in their ears and the question for NPR is how to get our programming into those earbuds. We launched our iPad app right when it debuted, and we have an iPhone app and a very robust website. The goal is to get our content to people however and wherever they are listening to it. There’s an organic evolution to our programming as well. I think that before Planet Money or before NPR Music was created, nobody would have imagined that either of those things would have existed in the form that they are now. It’s exciting to see where we go next, and hopefully it will be continuous growth as it has been for the last forty years.

There’s a piece in the book that talks about a period in the 1980s where NPR staff all seemed to wearing cowboy boots. Any holdovers from decades past?

Just looking around right now, I’m seeing sneakers, some wingtips, loafers, a couple pairs of high heels—definitely no cowboy boots.

“Amazon.