SOLS

Using 3D-printing technology to make the much-avoided subject of orthotics relevant and attractive

In an age of technology during which eye vision can be corrected in 10 minutes, prosthetic limbs are breaking ground in sensory feedback and computers can be controlled by brains, we’re surprisingly lacking in the orthotics department—an area that’s in high demand but hasn’t seen much innovation for a long time. This lack of attention has resulted in a lot of foot, back, knee and neck pain more oftentimes going untreated, as the word “orthotics” has become synonymous with “nursing home” or “social suicide.” SOLS, a NYC-based startup, is offering the ultimate customization in the long-neglected category through 3D-printed insoles, which will easily slip into shoes you already own, whether it’s your cherished Stan Smiths or a pair of ballet flats. Comfort— and proper body alignment—has never been so hassle-free.

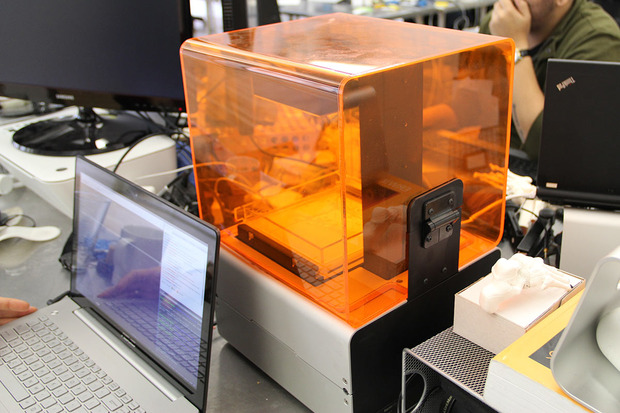

After raising about $1.75 million in seed funding, the now six-month-old company (currently a team of eight) is in the stages of product development; we visited their temporary office in Manhattan to learn more about what’s to come. Kegan Schouwenburg might not look like the stereotypical startup founder, but the design and manufacturing experience she’s had rivals that of others her age. However, it’s her infectious energy and gung-ho attitude that make her a formidable leader for this orthotics revolution.

Immediately after graduating from Pratt Institute with a background in industrial design, Schouwenburg and some friends started their own business called Design Glut and tackled the great monster of mass manufacturing early on. Similar to brands like Kikkerland or Areaware, Design Glut manufactured in China and distributed products all over the world; from MoMA to Urban Outfitters and Target. “It was an awesome experience but ultimately brought to light all of the challenges and problems with mass manufacturing, particularly as a young designer,” Schouwenburg tells CH. “You’re sort of like, ‘OK, just got out of school, I’ve been given this blank slate—oh, I can do anything! I want to be a designer!’ You don’t want to go work in a house or consultancy—you want to actually be able to see your ideas come to life.”

“That was what we’ve been taught in school, and ultimately what most people found (and some it took longer than others) but the barrier to entry in manufacturing was just so high that you either ended up being a Brooklyn designer that was making things by hand, or you went to go work for a large company and sort of gave up that dream,” Schouwenburg continues. “And for us, we were a little bit different because we made the jump to doing large-scale US production, then large-scale international production. It was not easy. It was a wild ride and at the end of that, I saw the company not scaling in a way that I wanted it to scale.”

Continually struggling with the barrier to entry in manufacturing, Schouwenburg saw 3D printing as the answer, as it would remove the enormous upfront costs associated with production. She then worked at Shapeways (the Etsy of 3D-printed goods) and essentially built their factory in Long Island City. Yet, Schouwenburg started getting restless: “I got so tired of seeing what people were doing with 3D printing,” she says, noting the trinkets and tchotchkes that populated the site, looking pretty but not so functional. “Here we have this great technology, but what are we making? Does the world really need that stuff?”

What does the world need? And where can this technology really, really take hold and change things?

“So the question for me became, what does the world need? And where can this technology really, really take hold and change things?” she says. Schouwenburg immediately thought of clothes shopping, considering it preposterous that we still go into stores and choose from pre-determined sizes, rather than buying something unique for our very uniquely shaped bodies. It not only applied to clothing, but to headphones, helmets, anything thing that fit the body—including shoes.

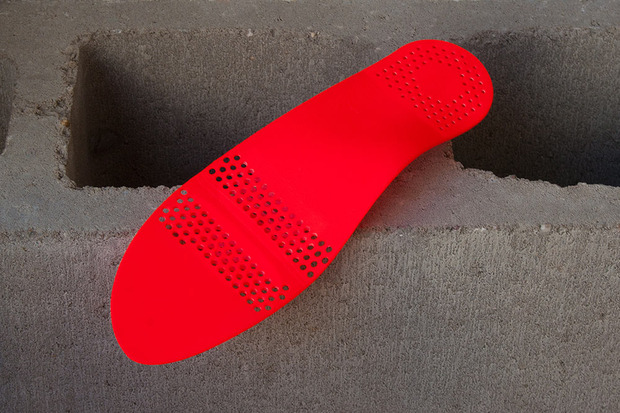

“Where can we use 3D printing to actually improve the product instead of be a replacement production method?” she continues. “And I love shoes. Shoes should be custom—let’s make my feet hurt less. But if we did shoes, ultimately we all have different tastes; you want to buy different shoes than I want to buy. But what if we customized the inside of the shoe instead of the outside, and what does that look like?” By changing the inside of shoes, Schouwenburg is focused on making a ubiquitous product that everybody could wear, rather than for a select few.

Ultimately, the simplest reason is that your body’s not aligned properly, because your feet and ankles aren’t aligned properly.

Schouwenburg herself grew up wearing orthotics, so she’s all-too-familiar with the grueling, inefficient (and expensive) process that is marred by human error—orthotics created by one podiatrist will wildly differ from that created by another podiatrist, even if it’s made for the same foot. Schouwenburg is intent on changing the medical sector by providing the doctors and community with a more efficient product and process but she’s also thinking with the consumer sector in mind next: “Let’s create a product that can fit in any shoe, that not only looks at the existing market—people that are experiencing pain and actually doing something about it—but the larger market of people that are experiencing pain and don’t even know how to fix it.”

Schouwenburg gives us a brief crash course in biomechanics. “Basically, there’s a proper body alignment that your ankles and legs should follow. Something like 70% of people don’t have that proper alignment and most of those people don’t even realize it. All they realize is that they have back pain or shoulder pain or neck pain or knee pain or hip pain—one of these variant pains. They talk about it, complain about it, they go get massages, maybe change their mattress; they look at all these different aspects that could be causing it but ultimately, the simplest reason is that your body’s not aligned properly, because your feet and ankles aren’t aligned properly.”

“What orthotics do is they effectively change the geometry of what your alignment is like, so it’s properly aligned,” says Schouwenburg. “They do that by customizing the surface of the foot bed; it positions your body in the right position. But a lot of people won’t ever do this because there’s this stigma around the whole product category: it’s this weird medical product, it’s expensive, it’s only doctors, it’s a hassle and it’s ugly and you have to wear ugly shoes. There’s all these reasons like why nobody wants to go down that rabbit hole.”

Part of what we’re doing is education and part of what we’re doing is transforming a product category.

“Part of what we’re doing is education and part of what we’re doing is transforming a product category,” Schouwenburg says. “You buy it out of desperation. It’s the same when you go to the store and you buy a pair of Dr Scholl’s insoles, you don’t really want to buy the product—you just buy it because you’re like, ‘God, I need something now!'”

Creating your own customized SOLS is a three-step process. First, you’ll wave a handheld tablet around your foot to scan it, and snap a photo of the back of your foot to give SOLS the alignment of your joint. The software will process the video through a series of algorithms and reconstruct a 3D model of your foot. A corrective shape will then be generated. The second part is gathering lifestyle information; the thickness and material used will be based upon your weight and activity level, creating responsive treatment zones. Finally, the customized orthotic will be 3D printed from durable, anti-microbial nylon material, then covered with a thicker leather. These insoles will be customized to the shoe; SOLS is building aggregate shoe models—like the three-inch pump or the boat shoe or the running shoe—so the inserts can slip in with ease. This process requires very little human interaction: it is not invasive for the patient, and reduces possible errors by doctors and technicians.

While we might immediately grab those soft, cushiony insoles in the drugstore when our feet are battered from a night out, plastic is in fact the crucial ingredient in the SOLS: “Most people think soft pillows equal comfort, but actually what that does is compresses under your weight and body, so that comfort goes away in like, two hours,” says Schouwenburg. “By creating these responsive structures out of an elastic material, we create something that never goes away, and consistently rebounds to your movement.”

SOLS is currently in beta trial in NYC, and will start selling through early adopters this spring. At launch, SOLS will be targeting patients with minor medical conditions; the service will be offered through doctors and customers who sign up on the website will be matched to a doctor near them, and receive an advanced medical product. By 2015, SOLS will be launching a consumer version that’s more comfort-focused and available directly from their site; anyone with the app can scan their foot on a smartphone or tablet, and receive a customized insert for about $100. Schouwenburg hints at SOLS potential plans for the future: to collaborate with major shoe companies and work to integrate customized insoles into the product themselves—therefore working “inside-out” rather than “outside-in.”

Image of SOLS in production courtesy of Seth Hanon, images of single insole courtesy of SOLS, all other photos by Nara Shin