“Faith Ringgold: American People” Captures and Conquers American Colonialism

At the New Museum, the first full retrospective of the artist pays tribute to her resistance and celebrates her radical joy

Revolutionary, painter, writer, educator, activist, sculptor and feminist are just some of the words that begin to describe Faith Ringgold, a visionary from Harlem, whose artwork since the 1960s laid bare the racist and patriarchal underpinnings of the United States. Unafraid to fight for the representation of Black women during the Civil Rights era (in art museums and the country at large) Ringgold not only exposed the true state of oppression, she also opened doors for those to come. For the first time, the true breadth of her work is being honored with a comprehensive retrospective at NYC’s New Museum. On view now until 5 June, Faith Ringgold: American People is an overdue tribute to the impactful artist.

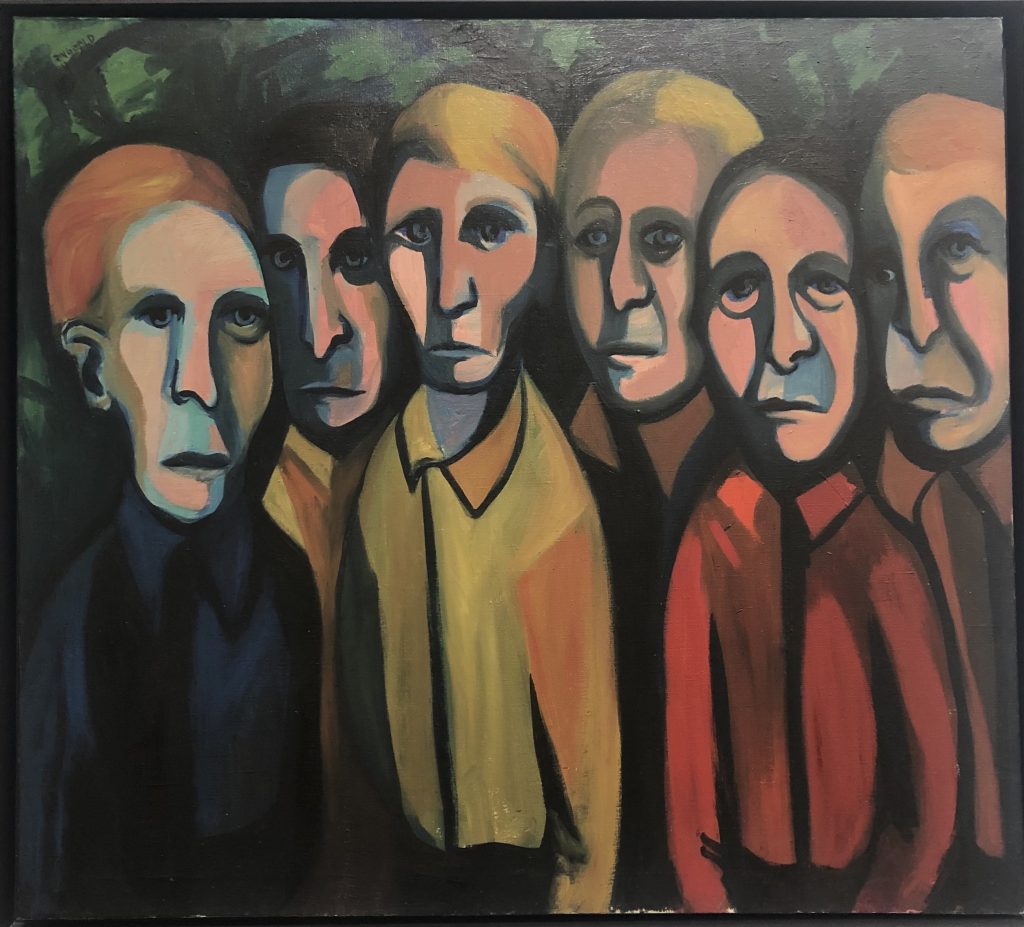

The exhibition—which stretches over three gallery floors—begins on the second level of the museum with Ringgold’s critical paintings from the 1960s and 1970s. This includes one of her most famous paintings “American People Series #20: Die”—an evocative, grisly portrait of the surmounting conflict between racial and class divides—as well as the mural from the same series, “The Flag is Bleeding,” in which Ringgold uses the American flag as a means of revealing the facade of national unity and democracy. “The first strong statement of the exhibit is Faith Ringgold is an amazing painter,” Massimiliano Gioni, the New Museum’s Edlis Neeson Artistic Director and curator for the exhibit, says. “Look at this work from the 1960s and early 1970s, simply incredible—and so important to understand the Civil Rights movement, Black Power and Black Panther movements.” Seen today, the paintings, including those in her Black Light Series, particularly resonate with the country’s present state.

Paintings give way to flyers, posters and other documents from protests that Ringgold supported, especially movements that advocated for space dedicated to Black art and Black women in museums. “This was another strand in our research that we wanted to highlight,” Gioni continues. “Ringgold advocated for reforming museums so that they could reflect the complexity and richness of American culture. This is really portentous because it proves the force of an artist who has changed the history of art, not only with her own work, but with her own presence. It is no exaggeration to say that Ringgold transformed institutions—from the inside and outside.”

On the third floor and second level of the retrospective, the artist’s sculptures, quilts and illustrations from her children’s books show how Ringgold constantly subverted art conventions. The floor opens with some of her sculptures, which she created after two trips to Africa. African costumes, masks and traditions of storytelling influenced her figures—which she referred to as “soft sculptures.” It’s a “gently subversive use of terminology, if compared with the ‘hard’ and obtuse sculptures of mostly male artists of minimalism in the same years,” says Gioni. “It’s a prime example of feminist art, determined to deconstruct ideas around craft and hierarchies of taste and power.”

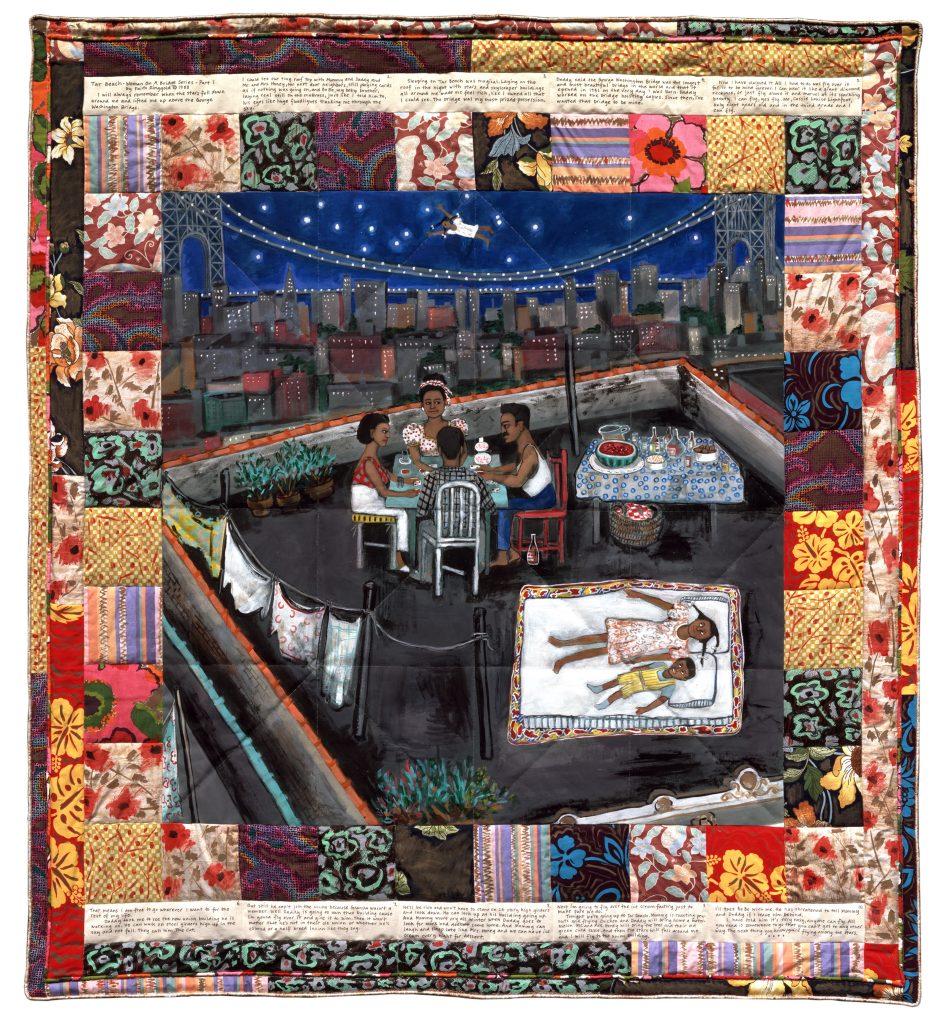

Through quilting and canvases with sewn fabric borders, the artist also deconstructed Western notions of craft, sometimes turning toward Tibetan thangkas as inspiration. Transcending white art traditions enabled Ringgold to use more liberating mediums to convey the complexities of her experiences and, in doing so, she “completely disregarded, transgressed and reinvented traditional definitions of taste, completely reconfiguring artificial distinctions between high and low culture,” Gioni adds. In her story quilts, namely “Tar Beach #2” and “Church Picnic,” scenes of familial joy and community resist the oppressive gender and racial disparities that dominate the other artworks.

Ringgold’s legacy continues into the corner of the third floor, where the drawings from her children’s book Tar Beach hang. The empowering book tells the story of a young girl called Cassie Louise Lightfoot who, on a warm summer’s night, flies over Harlem’s George Washington bridge. Ringgold uses flight to represent freedom, reclamation and self-possession, enabling the women in her stories—and the women beyond it—to soar above everything that seeks to repress them.

While liberating throughout, the retrospective perhaps feels the most hopeful and galvanizing on the last level, the fourth floor. Here, Ringgold’s The French Collection quilted series is brought together in its entirety for the first time in nearly 25 years. As Gioni tells us, this was an integral inclusion because it “was another way to present Ringgold as a consummate storyteller, one who had anticipated many contemporary conversations around modernity and colonialism.”

Stories using acrylic and printed and tie-dyed pieced fabric reclaimed the Western art cannon and Eurocentric spaces. In “Dancing at the Louvre,” for instance, a fictional character (and Ringgold’s alter-ego) Willia Marie Simone is traveling through Paris. Her narrative draws from Ringgold’s own experiences with struggling to find recognition in the industry, but rather than coming up against rejection and bias like Ringgold, Simone meets Pablo Picasso and Josephine Baker, rewriting personal and general history. At the Louvre, Simone dances in front of the “Mona Lisa,” evoking radical joy and freedom.

This collection of Ringgold’s work is a journey that begins with the exposure of the systemic oppression that shaped the United States to eventually ascend (quite literally, as it’s on the fourth floor) and overcome. Walking the full gallery of the retrospective is to be immersed in the faith Ringgold has in fighting higher institutional powers and flipping the script.

For Gioni, this was one of the compelling reasons that demanded the retrospective. “I think very few artists have reached well beyond the art world as Ringgold has, writing a parallel history of art and America. What makes her contribution even more remarkable is that every time she was confronted with an obstacle or with refusal and exclusion, not only did she continue to do her work, but she reinvented the very system in which she was working. She always says that ‘anyone can fly,’ and by looking at her work, one really can not help but believe her.”

Hero image is Faith Ringgold, “American People Series #18: The Flag Is Bleeding,” (1967), courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2022